Mitt Romney is being criticized for supporting “territorial taxation,” which is the common-sense notion that each nation gets to control the taxation of economic activity inside its borders.

While promoting his own class-warfare agenda, President Obama recently condemned Romney’s approach. His views, unsurprisingly, were echoed in a New York Times editorial.

President Obama raised…his proposals for tax credits for manufacturers in the United States to encourage the creation of new jobs. He said this was greatly preferable to Mitt Romney’s support for a so-called territorial tax system, in which the overseas profits of American corporations would escape United States taxation altogether. It’s not surprising that large multinational corporations strongly support a territorial tax system, which, they say, would make them more competitive with foreign rivals. What they don’t say, and what Mr. Obama stressed, is that eliminating federal taxes on foreign profits would create a powerful incentive for companies to shift even more jobs and investment overseas — the opposite of what the economy needs.

Since even left-leaning economists generally agree that tax credits for manufacturers are ineffective gimmicks proposed for political purposes, let’s set that topic aside and focus on the issue of territorial taxation.

Or, to be more specific, let’s compare the proposed system of territorial taxation to the current system of “worldwide taxation.”

Worldwide taxation means that a company is taxed not only on it’s domestic earnings, but also on its foreign earnings. Yet the “foreign-source income” of U.S. companies is “domestic-source income” in the nations where those earnings are generated, so that income already is subject to tax by those other governments.

In other words, worldwide taxation results in a version of double taxation.

The U.S. system seeks to mitigate this bad effect by allowing American-based companies a “credit” for some of the taxes they pay to foreign governments, but that system is very incomplete.

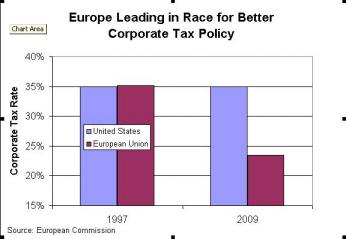

And even if it worked perfectly, America’s high corporate tax rate still puts U.S. companies in a very disadvantageous position. If an American firm, Dutch firm, and Irish firm are competing for business in Ireland, the latter two only pay the 12.5 percent Irish corporate tax on any profits they earn. The U.S. company also pays that tax, but then also pays an additional 22.5 percent to the IRS (the 35 percent U.S. tax rate minus a credit for the 12.5 percent Irish tax).

In an attempt to deal with this self-imposed disadvantage,  the U.S. tax system also has something called “deferral,” which allows American companies to delay the extra tax (though the Obama Administration has proposed to eliminate that provision!).

the U.S. tax system also has something called “deferral,” which allows American companies to delay the extra tax (though the Obama Administration has proposed to eliminate that provision!).

Romney is proposing to put American companies on a level playing field by going in the other direction. Instead of immediate worldwide taxation, as Obama wants, he wants to implement territorial taxation.

But what about the accusation from the New York Times that territorial taxation “would create a powerful incentive for companies to shift even more jobs and investment overseas”?

Well, they’re somewhat right…and they’re totally wrong. Here’s what I’ve said about that issue.

If a company can save money by building widgets in Ireland and selling them to the US market, then we shouldn’t be surprised that some of them will consider that option. So does this mean the President’s proposal might save some American jobs? Definitely not. If deferral is curtailed, that may prevent an American company from taking advantage of a profitable opportunity to build a factory in some place like Ireland. But U.S. tax law does not constrain foreign companies operating in foreign countries. So there would be nothing to prevent a Dutch company from taking advantage of that profitable Irish opportunity. And since a foreign-based company can ship goods into the U.S. market under the same rules as a U.S. company’s foreign subsidiary, worldwide taxation does not insulate America from overseas competition. It simply means that foreign companies get the business and earn the profits.

To put it bluntly, America’s tax code is driving jobs and investment to other nations. America’s high corporate tax rate is a huge self-inflected wound for American competitiveness.

Getting rid of deferral doesn’t solve any problems, as I explain in this video. Indeed, Obama’s policy would make a bad system even worse.

But, it’s also important to admit that shifting to territorial taxation isn’t a complete solution. Yes, it will help American-based companies compete for market share abroad by creating a level playing field. But if policy makers want to make the United States a more attractive location for jobs and investment, then a big cut in the corporate tax rate should be the next step.