I’m a big believer in the Laffer Curve, which is the common-sense proposition that changes in tax rates don’t automatically mean proportional changes in tax revenue. This is because you also have to think about what happens to taxable income, which can move up or down in response to changes in tax policy.

The key thing to understand is that incentives matter. If you raise tax rates and therefore increase the cost the engaging in productive behavior, people will be less likely to work, save, invest, and be entrepreneurial. And they’ll figure out ways to engage in tax avoidance and tax evasion to protect the interests of their families. In other words, taxable income will be lower because of higher tax rates.

Likewise, people will be more willing to earn – and report – taxable income if tax rates are reduced.

If you don’t believe me, look at this incredible data showing how the rich paid for more money after Reagan slashed their tax rates.

This doesn’t mean that “tax cuts pay for themselves.” That may happen in rare circumstances, but the real issue is the degree of “revenue feedback.”

For some types of tax changes, such as lowering tax rates on the “rich,” the revenue feedback may be very large because they have considerable control over the timing, level, and composition of their income.

In other cases, such as providing a child tax credit, the feedback may be very small because there’s not much of an impact on incentives to engage in productive behavior.

This doesn’t necessarily mean one type of tax cut is good and the other bad. It just means that some changes in tax policy produce revenue feedback and others don’t.

Even leftists recognize there is a Laffer Curve. They may argue that the “revenue-maximizing rate” is very high, with some claiming the government can impose tax rates of more than 70 percent and still collect additional revenue. But they all recognize that there’s a point where revenue-feedback effects are so strong that higher rates will lose revenue.

Actually, let me rephrase that assertion. There is a small group of people in the nation who claim that there’s no Laffer Curve. But that’s no surprise, the world is filled with weird people. Some genuinely think the world is flat. Some think the moon landings were faked. You can probably find some people who actually think the sun is a giant candle in the sky.

But what is surprising is that this small cadre of anti-Laffer Curve fanatics are at the Joint Committee on Taxation, which is the group on Capitol Hill in charge of providing revenue estimates on tax legislation.

They aren’t completely oblivious to the real world. They do acknowledge some “micro” effects of changes in tax rates, such as people shifting between taxable and non-taxable forms of compensation. But they completely reject “macro” changes such as changes in economic growth and employment.

So if we replaced the nightmarish income tax with a simple and fair flat tax, the JCT would assume no impact of GDP or jobs. If we went the other direction and doubled all tax rates, the JCT would blithely assume no change to the economy.

To give you an idea of why this is an extreme view, I want to share some polling data. Last week, I spoke at the national conference of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. As you can imagine, this is a crowd that is very familiar with the internal revenue code. They know the nooks and crannies of the tax code and they have a good sense of how clients respond when tax policy changes.

Prior to my remarks, the audience was polled on certain tax issues.

Some of the answers disappointed me. By a narrow margin, the crowd thought it would be a good idea if the overall tax burden increased. But here’s the response that fascinated me the most. The audience was asked what could be described as a Laffer Curve question. Specifically, they were asked, “Do you believe the growth potential of marginal tax rate cuts could lead to some degree of revenue feedback, even if not enough to be self-financing?”

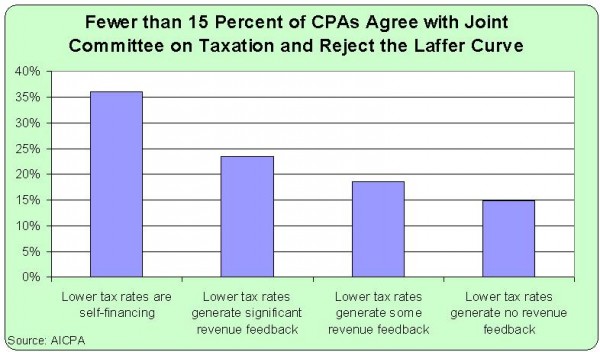

They had four possible responses. Here’s the breakdown of their answers.

These are remarkable results. A plurality (more than 36 percent) think the Laffer Curve is so strong that lower tax rates are self-financing. Even I don’t think that’s the case. Another 23.5 percent of respondents think there are very significant feedback effects, meaning that lower tax rates don’t lose much money.

There were also 18.6 percent who thought there were some Laffer Curve effects, though they thought the revenue feedback wasn’t very significant.

Less than 15 percent of the crowd, however, agreed with the Joint Committee on Taxation and said that lower tax rates have no measurable revenue feedback.

Why am I sharing this information? Well, we’re going to have a big debate in the next month or two about President Obama’s proposed class-warfare tax hike on investors, entrepreneurs, small business owners, and other rich people.

Supporters of that approach will cite Joint Committee on Taxation numbers to claim that the tax hike will generate a big pile of money.

That number will be based on nonsensical and biased methodology. In an ideal world, opponents will mock that number and expose the JCT’s primitive approach.

For additional information, here’s Part III of my video series on the Laffer Curve, exposing the role of the Joint Committee on Taxation.