One of the reasons why this blog is called International Liberty is that the world is a laboratory, with some nations (such as France) showing why statism is a mistake, other jurisdictions (such as Hong Kong) showing that freedom is a key to prosperity, and other countries (such as Sweden) having good and bad features.

It’s time to include Chile in the list of nations with generally good policies. That nation’s transition from statism and dictatorship to freedom and prosperity must rank as one of the most positive developments over the past 30 years.

Here’s some of what I wrote with Julia Morriss for the Daily Caller. Let’s start with the bad news.

Thirty years ago, Chile was a basket case. A socialist government in the 1970s had crippled the economy and destabilized society, leading to civil unrest and a military coup. Given the dismal situation, it’s no surprise that Chile’s economy was moribund and other Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Venezuela, and Argentina, had about twice as much per-capita economic output.

Realizing that change was necessary, the nation began to adopt pro-market reforms. Many people in the policy world are at least vaguely familiar with the system of personal retirement accounts that was introduced in the early 1980s, but we explain in the article that pension reform was just the beginning.

Let’s look at how Chile became the Latin Tiger. Pension reform is the best-known economic reform in Chile. Ever since the early 1980s, workers have been allowed to put 10 percent of their income into a personal retirement account. This system, implemented by José Piñera, has been remarkably successful, reducing the burden of taxes and spending and increasing saving and investment, while also producing a 50-100 percent increase in retirement benefits. Chile is now a nation of capitalists. But it takes a lot more than entitlement reform, however impressive, to turn a nation into an economic success story. What made Chile special was across-the-board economic liberalization.

We then show the data (on a scale of 1-10) from the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World, which confirm significant pro-market reforms in just about all facets of economic policy over the past three decades.

But have these reforms made a difference for the Chilean people? The answer seems to be a firm yes.

This has meant good things for all segments of the population. The number of people below the poverty line dropped from 40 percent to 20 percent between 1985 and 1997 and then to 15.1 percent in 2009. Public debt is now under 10 percent of GDP and after 1983 GDP grew an average of 4.6 percent per year. But growth isn’t a random event. Chile has prospered because the burden of government has declined. Chile is now ranked number one for freedom in its region and number seven in the world, even ahead of the United States.

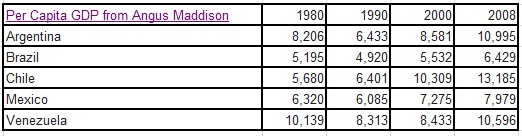

But I think the most important piece of evidence (building on the powerful comparison in this chart) is in the second table we included with the article.

Chile’s per-capita GDP has increased by about 130 percent, while other major Latin American nations have experienced much more modest growth (or, in the tragic case of Venezuela, almost no growth).

Perhaps not as impressive as the performance of Hong Kong and Singapore, but that’s to be expected since they regularly rank as the world’s two most pro-market jurisdictions.

But that’s not to take the limelight away from Chile. That nation’s reforms are impressive – particularly considering the grim developments of the 1970s. So our takeaway is rather obvious.

The lesson from Chile is that free markets and small government are a recipe for prosperity. The key for other developing nations is to figure out how to achieve these benefits without first suffering through a period of socialist tyranny and military dictatorship.

Heck, if other developing nations learn the right lessons from Chile, maybe we can even educate policy makers in America about the benefits of restraining Leviathan.

P.S. One thing that Julia and I forgot to include in the article is that Chile has reformed its education system with vouchers, similar to the good reforms in Sweden and the Netherlands.