I’m a strong believer in fundamental tax reform. We need a system like the flat tax to improve economic performance.

No tax system is good for growth, of course, but the negative impact of taxation can be reduced by lowering marginal tax rate(s), eliminating double taxation of saving and investment, and getting rid of loopholes that encourage people to make decisions for tax reasons even if they don’t make economic sense.

While the general public is quite sympathetic to tax reform and would like to de-fang the IRS, there are three main pockets of resistance.

- The class-warfare crowd is opposed to the flat tax for ideological reasons. They want high tax rates and punitive double taxation – even if the government winds up collecting less money.

- The lobbyists and special interest groups also are opposed to tax reform, along with the politicians that they cultivate. The tax code is a major source of political corruption, after all, and there would be a lot fewer opportunities to game the system and swap loopholes for political support if the 72,000 page tax code was tossed in a dumpster.

- Beneficiaries of certain tax preferences such as the mortgage interest deduction, the charitable deduction, and the state and local tax deduction are worried about tax reform, either because they are taxpayers who utilize the preferences or because they represent interest groups that benefit because the government has tilted the playing field.

This post is designed to allay the fears of this third group, specifically the folks who worry that tax reform might be bad news for charities.

The Wall Street Journal today published a pro-con debate on the charitable deduction. As you might expect, my role is to argue in favor of a simple and fair system that would eliminate all tax preferences.

Here’s some of what I wrote on the charitable deduction, beginning with the key point that economic growth is key because the biggest determinants of charitable giving are disposable income and net wealth.

Here’s some of what I wrote on the charitable deduction, beginning with the key point that economic growth is key because the biggest determinants of charitable giving are disposable income and net wealth.

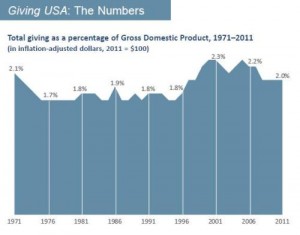

…the best way to help charities is to boost economic growth, which leaves people with more money to donate. And I think the best way to do that is to replace our current system with a simple and fair flat tax. …I don’t think there’s a compelling argument for the charitable deduction. …Over the decades, there have been major changes in tax rates and thus major changes in the tax treatment of charitable contributions. At some points, there has been a big tax advantage to giving, at others much less. Yet charitable giving tends to hover around 2% of U.S. gross domestic product, no matter what the incentive.

The final sentence in the above excerpt is key. The value of a tax deduction is determined by the tax rate. So in 1980, when the top tax rate was 70 percent, it only cost 30 cents to give $1 to charity. By 1988, though, the top tax rate was down to 28 percent, which means that the cost of giving $1 had jumped to 72 cents.

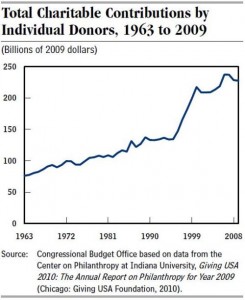

Yet charitable giving rose during the 1980s. Why? Because Reagan implemented reforms – such as lower tax rates – that produced a healthier economy.

Yet charitable giving rose during the 1980s. Why? Because Reagan implemented reforms – such as lower tax rates – that produced a healthier economy.

Some may wonder whether the example I just cited is appropriate since it focuses on the tax rate (and therefore the value of the tax deduction) for upper-income taxpayers.

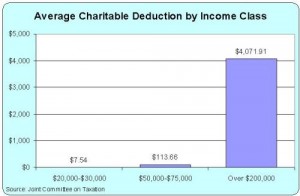

But there’s a good reason for that choice. The charitable deduction overwhelmingly goes to the rich.

Upper-income households are the biggest beneficiaries of the deduction, with those making more than $100,000 per year taking 81% of the deduction even though they account for just 13.5% of all U.S. tax returns. The data are even more skewed for households with more than $200,000 of income. They account for fewer than 3% of all tax returns, yet they take 55% of all charitable deductions.

I’m not against rich people, or against them lowering their tax liabilities. But I do want a tax system that generates more prosperity because that’s good news for the entire economy – including the nonprofit sector.

I’m not against rich people, or against them lowering their tax liabilities. But I do want a tax system that generates more prosperity because that’s good news for the entire economy – including the nonprofit sector.

Speaking of which, I think tax-deductible groups will become better and more efficient without the deduction.

Charities, meanwhile, get fatter and lazier because of that dynamic. Think of all the exposés in recent years about charities that devote an overwhelming share of their budgets to administrative costs and marketing expenses. No system will create perfect nonprofit groups, but cutting back or cutting out the deduction would break the cycle of inefficiency that now exists.

My debating partner is Diana Aviv, the head of Independent Sector, which is basically a trade associate in DC for charities. Here are the most relevant excerpts from her piece.

…more than 80% of those who itemized their tax returns in 2009 claimed the charitable deduction and were responsible for more than 76% of all individual contributions to charitable organizations.

That’s all fine and well. What she’s basically saying is that almost all rich people itemize and those rich people get the lion’s share of the benefit from the deduction.

But that’s not the key issue. What matters is whether the deduction makes a big difference for the amount that people contribute. Diana addresses that point.

According to a 2010 Indiana University survey, more than two-thirds of high-net-worth donors said they would decrease their giving if they did not receive a deduction for donations.

I don’t put complete faith in public opinion data, but let’s assume that this poll is a completely accurate snapshot of how rich people think they would react. But let’s balance that off with the real-world evidence from the 1980s, which shows that rich people gave more money in the 1980s after Reagan cut tax rates and dramatically lowered the value of the tax deduction.

I’m not saying the lower tax rates caused the increase in giving, but I am saying that the lower tax rates and other reforms helped boost the economy. And I’m saying that rich people gave more to charity because they had more income and more wealth.

I also can’t resist a comment about this excerpt.

Finally, there’s another important consideration. The charitable deduction is unique in that it’s a government incentive to sacrifice on behalf of the commonweal. Unlike incentives to save for retirement or buy a home, it encourages behavior for which a taxpayer gets no direct, personal, tangible benefit.

Huh?!? Diana’s entire article is based on the notion that people need to be bribed in order to contribute, yet she simultaneously says that taxpayers get “no direct, personal, tangible benefit.”

Let me close by tying this debate to the fiscal cliff negotiations. There is some discussion of capping itemized deductions as a way of extracting more money from the rich. That creates a bit of a quandary. Here’s something else I wrote for my part of the debate.

I don’t want to give more revenue to Washington. That’s like putting blood in the water with hungry sharks around. But if politicians are going to extract more money from the private sector anyway, reducing or eliminating the deduction is much less damaging to growth than imposing higher marginal tax rates.

That being said, that type of change – while not as bad for the economy – probably would have a negative impact on charitable giving.

My argument is that real tax reform can benefit the nonprofit sector because the loss of the deduction is more than offset by the pro-growth impact of lower tax rates, less double taxation, etc.

But if all politicians are doing is limiting the deduction as part of a money grab, then nonprofits get some pain and no gain.

Incidentally, this is why the nonprofit community should join the rest of us in fighting against an ever-climbing burden of government spending. If we don’t rein in Leviathan, it’s just a matter of time before politicians get rid of the deduction as part of a relentless search for more revenue.

I think it would be better for nonprofits – and for the rest of us – if we limit the size and scope of government and enact a tax system that produces the kind of prosperity that is beneficial for all sectors of the economy.