Many people think that my opposition to tax increases is ideological, but they’re wrong.

- If someone told me that I magically had the power to flick a switch and give the country a flat tax, but that simple and fair tax system would only be possible if the rate was set high enough to give the government an extra $100 billion of revenue each year, I would take the deal in a heartbeat.

- If I was given the opportunity to abolish the Departments of Energy, Education, Transportation, Agriculture, and Housing and Urban Development, but I had to give the politicians an extra $100 billion of revenue per year in exchange, I’d say yes right away.

- And if I had the chance to adopt Medicare reform, Medicaid reform, and Social Security reform, and all I had to give up was $100 billion of added annual tax revenue, I wouldn’t hesitate to give my approval.

In other words, I’m willing to go along with a tax hike so long as I get an acceptable offer. And my definition of acceptable offer isn’t even that onerous. I’m willing to acquiesce to a tax hike if the net long-run effect is more freedom, liberty, and prosperity.

Heck, I’ve even said on national TV that I would go back to Bill Clinton’s tax policy if I could undo all the reckless spending and regulation of the Bush-Obama years.

So if my views on this topic are so open-minded, reasonable, and pragmatic, why am I always writing posts that are critical of tax hikes?

But before answering that question, let’s present the views of some other people. At the end of last month, I was at the Economics Bloggers Forum put on by the good folks at the Kauffman Foundation in Kansas City. Lots of interesting people from all parts of the spectrum.

My favorite panel was entitled “After the Election, How Do We Fix the Budget?” and it featured John Goodman of the National Center for Policy Analysis, Ezra Klein of the Washington Post, and Donald Marron of the Tax Policy Center.

All of the presentations were interesting, but I want to focus on Donald’s remarks. He made the case that a big budget deal with higher taxes might be desirable because that kind of “grand bargain” would include pro-growth tax reform and much-need entitlement reform.

You can watch his presentation by clicking on the “Panel 2″ video and going to the 17:15 mark. Donald’s argument is that tax preferences are inefficient and distorting, so it would be a win-win scenario to get rid of them as part of a deal that also deals with entitlement programs. The government does collect more revenue, but he’s describing a worthwhile package. At least in theory.

Donald’s not the only person to make this argument. Here’s some of what Morgen Richmond recently wrote at the conservative Hotair.com website.

I am mystified why the GOP has adopted such a hard line when it comes to tax policy, particularly within the framework of a budget deal which would include a major re-structuring of federal entitlement programs. …given what may be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to finally deal with entitlements, personally, as a member of the near-1%, I would at least grudgingly accept a moderate tax increase knowing that we’ve set the nation on a sustainable path. Further, I would gladly – enthusiastically! – support the possibility of a moderate tax increase as part of the 2012 GOP budget platform, as long as it’s clear that this would only be on the table as part of a comprehensive deal which included entitlement reform, along the lines proposed by Ryan. …I’m…suggesting we…consider adding a little revenue from higher wage earners, or least a placeholder to do so. Just something to allow our nominee to credibly argue that when it comes to restoring the fiscal prosperity of our nation, everything is on the table. Because frankly, it should be.

Morgen’s premise is to the left of Donald’s because he is willing to trade class-warfare tax hikes for entitlement reform. But this also might be an acceptable swap.

And remember the GOP presidential debate, where all the Republican candidates rejected a hypothetical deal featuring $10 of spending cuts for every $1 of tax hikes? Well, here’s what Kevin Williamson of National Review said in response.

Every candidate said he would oppose a…plan that contained a 10:1 ratio of cuts to taxes. Chalk one up to the crazies. If Congress wanted to get rid of tax exemptions and exclusions amounting to $100 billion in new taxes in exchange for $1 trillion in cuts, and Republicans turned the deal down, I would personally drive down to Washington and pelt them with rotten vegetables, and possibly with rocks. $100 billion in new taxes plus $1 trillion in cuts balances the budget in 2012.

I wouldn’t mind throwing rocks at politicians, so sign me up. And I’d also take the 10-1 deal Kevin is describing.

But here’s where theory gets crushed by reality. Marron, Richmond, and Williamson are describing deals that will never happen. Sort of like me speculating on whether I’d be willing to play for the New York Yankees, but only if they guarantee me $5 million per year.

As a practical matter, I’m opposed to tax increases because the odds of getting a deal that moves policy in a constructive direction are somewhere between…well, I was going to write “slim and none,” but it’s more accurate to say that the odds range from are-you-smoking-crack to you-must-be-f-ing-kidding.

Here are three reasons why.

1. The supposed spending cuts in a “grand bargain” would be based on dishonest Washington math. If I’m supposed to take some sort of deal, whether it’s $10-$1, $3-$1, or $1-$1, I want the spending cuts to be genuine, not the usual game of having a program grow by 6 percent instead of 8 percent and pretending there’s been a 2 percent cut. Sadly, what I want doesn’t matter. Budget policy in Washington is governed by a fundamentally dishonest process that says that reductions in increases are actually cuts.

2. Proponents of the grand bargain always say that any new tax revenues will be generated by closing loopholes, deductions, exclusions, and other preferences. Since I’ve railed against corrupt tax-code distortions, that should be music to my ears. Unfortunately, as I explained last year, the people at the Joint Committee on Taxation use a very biased benchmark when measuring so-called tax expenditures. As a result, a “grand bargain” would be more likely to result in an increase in the (already onerous) double taxation of income that is saved and invested rather than the elimination of genuine loopholes such as the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance. And if Obama prevailed, we’d also have higher income tax rates as well.

3. Not all entitlement reform is created equal. The right kind of reform changes the structure of programs to promote market forces, federalism, and fiscal sustainability. The wrong kind of reform, by contrast, keeps the existing structure in place and tries to address the fiscal train wreck with some combination of means-testing and price controls. Now, take a wild guess at which approach was adopted by the Gang of Six and the Simpson-Bowles fiscal commission, plans that often are cited as providing a framework for a grand bargain? You won’t be surprised to learn that neither plan included the real entitlement reforms from the Ryan budget.

Simply stated, there is no practical way to get a good deal from either the Democrats in the Senate or the Obama Administration. Notwithstanding the good intentions of Marron, Richmond, and Williamson, any grand bargain would be a failure that leads to higher spending and more red ink, just as we saw after the 1982 and 1990 budget deals. The tax increases would not be relatively benign loophole closers. Instead, the economy would be hit by higher marginal tax rates on work, savings, investment, and entrepreneurship. And the entitlement reform would be unsustainable gimmicks rather than structural changes to fix the underlying programs.

This is a prediction, not a statement of fact, so I could be wrong. Indeed, I hope my prediction is wrong. But history is on my side, so I think supporters of the so-called grand bargain have an obligation to tell us why a budget deal today would produce a good result notwithstanding the real-world concerns outlined above.

And speaking of history, the left sometimes claims that the 1993 tax hike generated budget surpluses later in the decade, but numbers from Bill Clinton’s Office of Management and Budget puncture this myth.

The bottom line is that more than 100 percent of America’s fiscal problem is because of too much spending. As such, even though higher taxes theoretically could be part of a grand bargain to address the nation’s spending crisis, I’m reminded of Samuel Johnson’s famous quote about second marriages being a triumph of hope over experience.

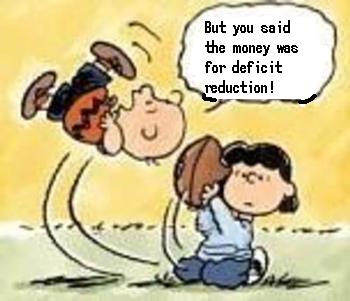

But some second marriages are successful, so proponents of the grand bargain are more akin to people going on safaris in search of Bigfoot, the abominable snowman, unicorns, and the Loch Ness monster. But I’ll bestow upon them a Charlie Brown Award, so at least they’ll have something to hang on the wall.

P.S. Since I don’t want to tear down the ideas of others without offering a solution of my own, here’s the simple approach that’s needed to balance the budget.