Two days ago, I explained that tax increases are bad policy.

More specifically, I warned that giving more money to government exacerbates fiscal problems because politicians respond to the expectation of more revenue by spending more than otherwise would be the case. And since they usually over-estimate how much revenue a tax hike will generate, that creates an even bigger fiscal mess.

Not surprisingly, I cited Europe to bolster my case. The tax burden has increased enormously in Europe over the past several decades, but that obviously hasn’t prevented a fiscal crisis in nations such as Greece and Portugal. And tax hikes haven’t precluded deteriorating conditions in countries such as Belgium and France.

But I also cited Illinois, which just got downgraded by Moody’s – even though state politicians just imposed a record tax hike.

This caused some angst for a lefty blogger in Illinois, who wrote that, “Operational spending is down since the Illinois tax hike.”

I gather he thinks this is some sort of gotcha moment, but two sentences later he admits that, “If Illinois hadn’t increased its taxes, it would’ve had to cut $7 billion more from spending to balance its budget.”

In other words, his post confirms my point about higher taxes translating into higher spending. He openly admits that the tax hike was a substitute for spending restraint.

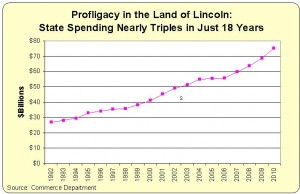

What makes his concession so remarkable is that my argument wasn’t even based on one-year fiscal decisions. I”m much more concerned with trend lines, and you can see from the chart that Illinois politicians have been promiscuously profligate in recent years.

Indeed, I developed “Mitchell’s Golden Rule” to underscore the importance of restraining the burden of government so that, over time, it grows slower than the private economy. That obviously hasn’t been happening in Illinois in recent decades – and it’s not likely to happen in future decades if politicians figure out ways of grabbing more revenue.

Speaking of revenue, my accidental friend from Illinois also tries to debunk my point about the Laffer Curve by writing that, “The Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability has repeatedly said this year that revenues from the tax increase are coming in as the ‘politicians’ expected.”

Well, I don’t know about you, but this is not exactly a rigorous rebuttal. He doesn’t provide a revenue forecast from the pre-tax-hike era or a more recent forecast from the post-tax-hike era, so we can’t make any comparisons. Instead, we’re supposed to blindly accept vague assurances from some Commission.

This doesn’t mean that forecasts don’t exist or that the bureaucrats were wrong about their short-run projections. But that’s not the main issue. The key question is what will happen to revenue over a period of years, particularly once entrepreneurs, investors, and businesses have time to adjust their behavior in response to the more onerous tax regime.

The changes can be enormous, as demonstrated in this post showing how rich people paid five times as much federal income tax after Reagan cut the top tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent.

It will take a few years before we have a decent idea about the consequences of the Illinois tax hike. But since Illinois is copying European-style fiscal policy, don’t be too surprised if the result is European-style economic malaise.