Thanks to decades of reckless spending by European welfare states, the newspapers are filled with headlines about debt, default, contagion, and bankruptcy.

We know that Greece and Ireland already have received direct bailouts, and other European welfare states are getting indirect bailouts from the European Central Bank, which is vying with the Federal Reserve in a contest to see which central bank can win the “Most Likely to Appease the Political Class” Award.

But which nation will be the next domino to fall? Who will get the next direct bailout?

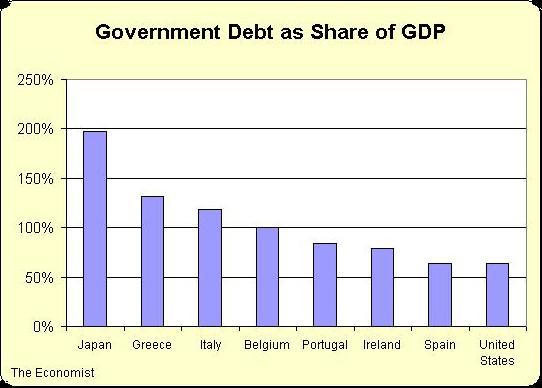

Some people think total government debt is the key variable, and there’s been a lot of talk that debt levels of 90 percent of GDP represent some sort of fiscal Maginot Line. Once nations get above that level, there’s a risk of some sort of crisis.

But that’s not necessarily a good rule of thumb. This chart, based on 2010 data from the Economist Intelligence Unit (which can be viewed with a very user-friendly map), shows that Japan’s debt is nearly 200 percent of GDP, yet Japanese debt is considered very safe, based on the market for credit default swaps, which measures the cost of insuring debt. Indeed, only U.S. debt is seen as a better bet.

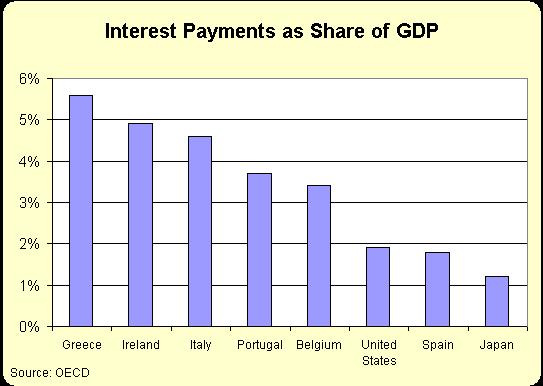

Interest payments on debt may be a better gauge of a nation’s fiscal health. The next chart (2011 data) shows the same countries, and the two nations with the highest interest costs, Greece and Ireland, already have been bailed out. Interestingly, Japan is in the best shape, even though it has the biggest debt. This shows why interest rates are very important. If investors think a nation is safe, they don’t require high interest rates to compensate them for the risk of default (fears of future inflation also can play a role, since investors don’t like getting repaid with devalued currency).

Based on this second chart, it appears that Italy, Portugal, and Belgium are the next dominos to topple. Portugal may be the best bet (no pun intended) based on credit default swap rates, and that certainly is consistent with the current speculation about an official bailout.

Spain is the wild card in this analysis. It has the second-lowest level of both debt and interest payments as shares of GDP, but the CDS market shows that Spanish government debt is a greater risk than bonds from either Italy or Belgium.

By the way, the CDS market shows that lending money to Illinois and California is also riskier than lending to either Italy or Belgium.

The moral of the story is that there is no magic point where deficit spending leads to a fiscal crisis, but we do know that it is a bad idea for governments to engage in reckless spending over a long period of time. That’s a recipe for stifling taxes and large deficits. And when investors see the resulting combination of sluggish growth and rising debt, eventually they will run out of patience.

The Bush-Obama policy of big government has moved America in the wrong direction. But if the data above is any indication, America probably has some breathing room. What happens on the budget this year may be an indication of whether we use that time wisely.