The left wanted to get one thing from the Supercommittee, and that was to seduce gullible Republicans into a 1990-style tax increase deal in order to enable bigger government.

But I was pleasantly surprised when GOPers failed to surrender, which means that taxpayers didn’t get raped and pillaged. But winning a battle is not the same as winning a war.

The real fight is now whether the sequester is allowed to happen. In other words, will politicians preserve the provision that will automatically slow the growth of the federal budget so that spending over the next 10 years grows by about $2.0 trillion rather than $2.1 trillion.

This may not seem like much of an achievement, but it is a very important indicator of what will happen in the future. If we want to protect against higher taxes in the long run, we need to figure out how to restrain government spending.

At the very least, this means following Mitchell’s Golden Rule so that the private sector grows faster than government. This would slowly but surely shrink the burden of federal spending as a share of economic output, though actual spending cuts would be preferable and they would more quickly get us where we need to be.

The main obstacle to the sequester, at least on the right, is that it would slow the growth of the defense budget. According to recent calculations, the Pentagon budget would increase by only about $100 billion over the next 10 years if the sequester is implemented.

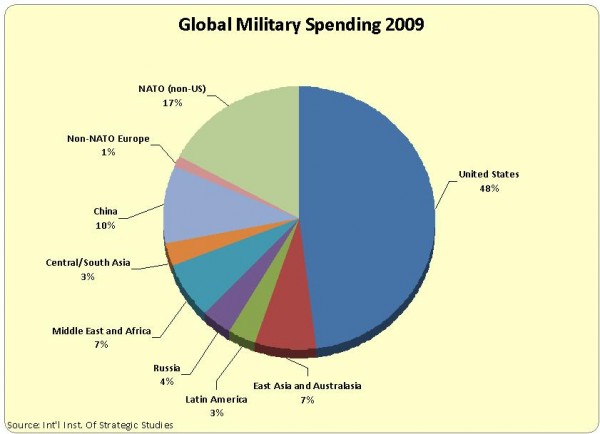

That might not be enough to keep pace with inflation, and some are wondering whether this puts America’s national security at risk. But this chart, which was developed by Cato Institute colleagues, shows that the United States dominates global defense spending.

Not only does the United States account for 48 percent of total defense spending, our allies in Europe and the Pacific Rim account for another 24 percent of military outlays.

And even if we use an absurdly expansive definition of possible enemies (Russia, China, all of Central/South Asia, and the entire Middle East and Africa), the military expenditures by those nations and regions don’t even amount to one-fourth of the world total.

More important, the combined spending by all potential adversaries is only about one-half of what the United States is spending, and only one-third of the combined spending of the United States and our allies.

This isn’t an argument for blindly slashing the defense budget. Nor is it an argument that says a sequester is the best way to prune military spending. But it certainly suggests that some modest restraint won’t put America in danger.

Moreover, perhaps the sequester will trigger some much-needed analysis of how best to protect America’s national security.

Maybe Mark Steyn and Steve Chapman are correct and it is time to revisit our spending on NATO, an alliance that was put together to fight the Warsaw Pact, an adversary that no longer exists.

Perhaps it means we shouldn’t spend huge sums of money to defend South Korea, which is far richer and stronger than its crazy northern neighbor.

Or maybe it means that the United States shouldn’t be engaged in nation-building exercises that exacerbate anti-American sentiment in other nations.

I’m not a defense/national security expert, so I don’t pretend to know the right approach to all of these issues.

But I have some familiarity with the way things get done in Washington. Politicians, lobbyists, interest groups, and bureaucracies will all act like the world is coming to an end if budgets are not endlessly expanded. That’s just as true for the Pentagon as it is for all other parts of the federal government.