One of the tax increases buried in Obamacare was an onerous and intrusive “1099″ scheme that would have required businesses to collect tax identification numbers for just about any vendor and then send paperwork to the IRS whenever they did more than $600 of business.

- Send one of your sales people to New York for a couple of nights? They would have to get the tax ID for the hotel and submit a form to the IRS.o Buy a printer for the office? The printer company would need to provide a tax ID and the purchaser would have to submit a form to the IRS.

- Have a retirement dinner for somebody in the accounting department? Get the restaurant’s tax ID and submit another form to the IRS.

This system was seen as a nightmare, even leading to rather amusing cartoons mocking the law and showing how it would expand an already abusive IRS. And in a rare fit of common sense, the 1099 requirement was repealed earlier this year.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that an international version of Obamacare’s 1099 scheme also was enacted early last year. But since the burden is largely falling on foreigners, there’s no groundswell among voters to repeal the law – even though it will impose far more damage on the American economy.

Known as the FATCA (the acronym for the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act), this law was included as a revenue-raising provision to pay for one of Obama’s failed stimulus bills.

But while the bill didn’t create jobs, it has created a giant nightmare for all sorts of people and firms – including foreign financial institutions that may now decide that it’s no longer worth the trouble to invest in America.

Consider these excerpts from a shocking story in the Financial Times.

…one of Asia’s largest financial groups is quietly mulling a potentially explosive question: could it organise some of its subsidiaries so that they could stop handling all US Treasury bonds?

Their motive has nothing to do with the outlook for the dollar.

…Instead, what is worrying this particular Asian financial group is tax. In January 2013, the US will implement a new law called the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act.

…[T]he new rules leave some financial officials fuming in places such as Australia, Canada, Germany, Hong Kong and Singapore. …[I]implementing these measures is likely to be costly; in jurisdictions such as Singapore or Hong Kong, the IRS rules appear to contravene local privacy laws. …Terry Campbell, head of Canada’s banking association, points out, the rules are essentially akin to “conscripting financial institutions around the world to be arms of US tax authorities”.

…[T]he IRS is threatening to impose a withholding tax of up to 30 per cent on sales of US assets by groups that it deems to be “non-compliant” – and the assets could include US shares or US Treasury bonds.

Hence the fact that some non-US asset managers and banking groups are debating whether they could simply ignore Fatca by creating subsidiaries that never touch US assets at all.

“This is complete madness for the US – America needs global investors to buy its bonds,” fumes one bank manager. “But not holding US assets might turn out to be the easiest thing for us to do.”

…“Right now my board is probably as concerned about political risk in America as Indonesia, from a business perspective – perhaps more so,” says the head of one large global bank. It is a complaint that American politicians ignore at their peril.

Many people, when hearing about foreign banks resisting demands by the IRS, might automatically assume the issue involves jurisdictions with strong human rights laws with regards to financial privacy, such as Switzerland or the Cayman Islands.

There are plenty of those stories, to be sure, but American tax law has become so bad that the IRS is causing headaches and anger even in nations with high taxes and weak protection of client data.

Here’s an excerpt from an article from the Financial Post in Canada.

Toronto-Dominion Bank is putting up a fight against a new U.S. regulation that would compel foreign banks to sort through billions of dollars of deposits to find U.S. citizens who might be hiding money. According to Bloomberg News, TD has complained that the proposed IRS rule is unreasonable because it would require the bank to make US$100-million investment in new software and staff. Other lenders resisting the effort include Allianz SE of Germany, Aegon NV of the Netherlands and Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Bloomberg said. Now the Canadian Bankers association has joined the fray. In an emailed statement the CBA called the requirement “highly complex” and “very difficult and costly for Canadian banks to comply with.” …According to the New York-based Institute of International Bankers, major global banks would end up spending US$250 million or more to comply with the regulation in terms of new technology employee training.

The vast majority of Americans are very fortunate that they don’t have any personal interactions with the IRS’s onerous international tax rules. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t care. The tax treatment of cross-border economic activity can have enormous implications for America’s prosperity, as I’ve already explained in my discussions of a reckless IRS regulation that could drive more than $100 billion of capital out of American banks.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. FATCA is far more onerous and extensive, so the damage will be much greater. Not surprisingly, the law utterly fails to satisfy any sort of cost-benefit analysis.

From the perspective of politicians, the “benefit” is more tax revenue. So how does FATCA score on this basis? During the 2008 campaign, Obama claimed this policy would generate $100 billion of additional revenue every year. When it came time to score the legislation, however, the Joint Committee on Taxation predicted that the law will generate only $870 million per year. That’s a big drop-off, even by the shoddy standards of Washington.

Yet for this tiny amount of revenue, the law imposes a giant regulatory burden on all individuals, companies, and institutions that meet two criteria: 1) They have some form of cross-border economic activity, and 2) They have a business or citizenship relationship with the United States.

Americans living overseas are one of the groups that will be severely penalized. Simply stated, foreign financial institutions are treating U.S. citizens like lepers because they don’t want to deal with the IRS and be deputy enforcers of terrible American law. Here are comments from some of Americans living in other nations (all of whom wish to remain anonymous because they fear being targeted by a thuggish IRS).

- From an American with a spouse working in Germany – “…when he went to create an account, he discovered that the bond fund could not be sold to US citizens.”

- From a non-profit group operating in Europe – “…we received notification from [bank redacted] that they were terminating our account.”

- From an American working in Switzerland – “I’m in the process of having my…accounts with [bank redacted] forced closed, except for the mortgage. I’ve been unable to open an account with any other Swiss bank.”

- From an American living in Belgium – “…my portfolio of investments held at their bank was blocked. …He advised me that as of that date, I could no longer trade, but could only hold, sell or transfer my portfolio. I was banned from trading in either US stocks or all others.”

- From a retired teacher in Germany – “I was denied the policy because I am an American citizen. My agent very clearly said that he could sell the policy that I wanted to any other nationality, except me-because I was American!”

- From an American working in Saudi Arabia – “As a resident of Saudi Arabia, I have twice been rejected as a customer, purely on the basis of my US citizenship. In both instances, I was told that increased administrative and compliance burdens imposed by US authorities have led the banks in question to refuse to open securities accounts for American citizens.”

- From an American in Japan – “All of these banks and institutions are cutting me off from participation in any but the most simple of basic bank account. Why? Because they do not want to take the time and instill the systems and carry the cost of reporting the income of each of their US citizen clients to the US government.”

- From an American married to a European – “I have been unable to gain legal advice in Switzerland regarding US Wills and Guardianships because [bank redacted] lawyers are ‘not permitted to speak to Americans about legal, tax or banking matters in specific terms.’”

- From an American married to a European – “The company who has been holding my modest UK share portfolio wrote to me in September 2010 saying they were closing my account. They were removing all US persons from their client base due to the increased reporting and audit costs placed on them by the Fatca legislation.”

- From an American in Europe with a foreign spouse – “They sent me a letter saying: Our records show that you are an American citizen. Because of various strict new American rules regarding securities accounts held by American shareholders, we are closing such accounts including yours.”

- From an American assigned overseas by his company – “I was extremely surprised and outraged by the fact that not one bank (including foreign branches of US banks!) would allow me to open a simple savings account to pay my rent and bills. All of the banks cited my US citizenship and the difficulties they experience with the US government.”

- From an American in Spain – “I have been forced to close a U.S. bank account due to being an overseas citizen and cannot open new bank or brokerage accounts in the U.S. I am also being denied the opening of new brokerage accounts in Spain.”

Last but not least, another set of victims are foreigners who legally reside in the United States. That makes them tax residents according to American tax law, which means that they also are lepers from the perspective of foreign financial institutions.

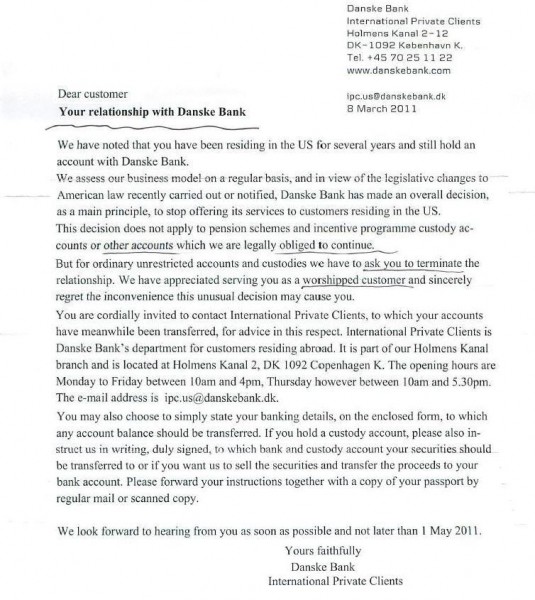

Let’s close this lengthy post by including this letter from a Danish bank to a Danish citizen living in the United States. Once again, identifying information is redacted because the person did not want to suffer IRS persecution (it should disturb all of us, by the way, that there is such universal fear of IRS thuggery).