September 2010, Vol. X, Issue I

An Update on the OECD’s Campaign Against Tax

Competition, Fiscal Sovereignty, and Financial Privacy

By Daniel J. Mitchell

The Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has an ongoing project to prop up Europe’s inefficient welfare states by attacking tax competition in hopes of enabling governments to impose heavier tax burdens. This project received a boost when the Obama Administration joined forces with countries such as France and Germany, but the tide is now turning against high-tax nations – particularly as more people understand that such an approach inevitably leads to Greek-style fiscal collapse. Looming political changes in the United States will further complicate the OECD’s ability to impose bad policy. Because of these developments, low-tax jurisdictions should be especially wary of schemes to rush through new anti-tax competition initiatives at the Singapore Global Forum.

The next chapter in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) campaign against tax competition will take place at the Global Tax Forum in Singapore, Sept 29-30, 2010. The OECD, dominated and controlled by European welfare states, has been working for more than a decade to impose punitive international tax rules in order to prop up the inefficient policies of member nations such as France and Greece. This illiberal effort is now being pursued with even greater urgency because politicians from those nations hope to find new revenue sources to postpone the inevitable collapse of their bankrupt and corrupt fiscal systems.

Current status

Unfortunately, high-tax nations have made progress on their anti-tax competition efforts in the past few years. Low-tax jurisdictions, faced with direct and indirect threats of sanctions from powerful nations, have been forced to weaken their human-rights policies by agreeing that privacy laws no longer protect foreign investors. Indeed, jurisdictions are being coerced to sign tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs) to provide confidential data upon request to high-tax OECD countries.

Nailing down a network of these so-called information-exchange-agreements (a bit of a misnomer since the information flow is in one direction) is the main official agenda of this year’s conference.

This effort undermines good tax policy, which is based on the common-sense principle of territorial taxation, but the greater worry is whether the high-tax nations plan to make new demands. At last year’s OECD Global Forum, for instance, high-tax nations sprang the “Mexico City Surprise,” which was an attempt to give the OECD broad authority to attack tax avoidance and other legal forms of tax planning.

Why the campaign against tax competition will never cease: theory and reality

The OECD’s disingenuous stunt last year should not have been a surprise. The politicians from high-tax nations who control the OECD are guided by bad theory and motivated by…well, greed.

The bad theory is “capital export neutrality,” which is an odd name, but it refers to an ideological notion, taught by left-wing law professors, that taxpayers should never be allowed to benefit from better tax policy in other jurisdictions. OECD bureaucrats (as well as officials from finance ministries and finance departments in high-tax nations) are heavily influenced by the CEN mindset and this leads them to support policies designed to hinder all forms of tax competition.

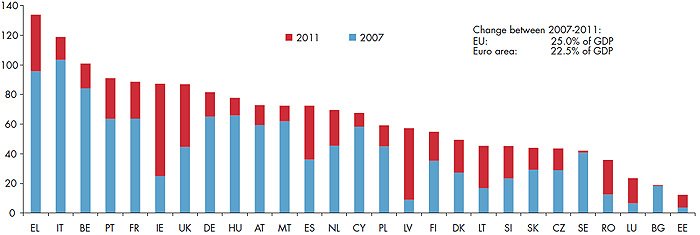

Politicians, of course, have no understanding of the theoretical issues. A common joke in the tax community is that most elected officials couldn’t even spell CEN. They simply want more tax revenue to buy more votes, and these base impulses are particularly acute as they all face some level of Greek-style fiscal chaos in the near future. Fiscal forecasts and analyses by the OECD, EU, IMF, and private entities paint the same grim picture. Most European nations have taxed and spent themselves into fiscal cul-de-sacs, and the anti-tax competition effort is an endeavor to buy more time before the house of cards collapses.

The next steps

The OECD has its own version of the Brezhnev Doctrine (“what’s mine is mine; what’s yours in negotiable”). Now that low-tax jurisdictions have been coerced into signing TIEAs, the Paris-based bureaucracy almost certainly will expand its demands. Last year’s Mexico City Surprise is an example of this pattern.

Low-tax jurisdictions should be fully aware of the OECD’s bad-faith approach. Some policy makers from these jurisdictions are being duped into thinking they are “partners” with the OECD and that signing TIEAs will end the harassment from high-tax nations.

This is a triumph of hope over reality. There’s an old saying that feeding your leg to a crocodile does not turn him into a vegetarian. The same is true about appeasing the OECD. Just as a crocodile will come back for another meal, the opponents of tax competition will put forth new demands.

The following policies are the most immediate areas of concern.

1. Automatic information sharingThe current system of TIEAs allows high-tax nations to request information about specific taxpayers if there is some reason to suspect they are investors in low-tax jurisdictions. It is quite likely that this system will not generate the desired windfall of new tax revenue. This is largely because estimates of foregone tax revenue are wildly exaggerated, but the OECD and its allies will argue that the “upon-request” model in inadequate and begin to push for automatic information sharing. This, of course, raises all sorts of concerns regarding data integrity, identity theft, misuse of information, and human rights abuses. And it would mean very high costs imposed on low-tax jurisdictions.

2. Attack on tax planning and tax avoidance

The “Mexico City Surprise” failed last year, but that does not mean the OECD and high-tax nations will let the issue drop. The CEN theory makes no distinction between tax evasion and tax avoidance. Revenue-hungry politicians also don’t care whether they are missing out on potential tax revenue because of legal or illegal actions. There is an assumption that substantially more tax can be collected from both rich people (high net worth individuals, or HNWIs) and corporations (particularly multinationals), and that this will require coordinated action. This would lead to much higher compliance burdens on targeted taxpayers, but also costly new rules and reporting regimes for low-tax jurisdictions.

3. Global and/or universal financial taxes

There is a drumbeat for some sort of worldwide financial tax. In some cases, advocates envision a global tax, perhaps imposed and collected by an international bureaucracy. The Tobin Tax would be one example of this approach. In other cases, proponents urge bank taxes imposed on a country-by-country basis, but with some sort of agreement that all jurisdictions participate since a tax cartel is needed to prevent investors/depositors from shifting funds across national borders. This latter approach often is characterized as a response to bailouts, either to recoup funds already spent or to accumulate funds for potential future bailouts. Regardless of the design, and regardless of the stated reason for the tax, politicians from high-tax nations are salivating at the thought of additional revenue. Imposing new costs on the “offshore” world would be a fringe benefit, sort of akin to icing on a cake.

4. Savings tax directive, part II

The European Union already has implemented a version of automatic information sharing, but the politicians are very unhappy with the system because it does not apply to all forms of capital income and asset accumulation and because some of the participating nations (all EU countries, plus a handful of non-EU jurisdictions) can choose a withholding tax instead. This system has not generated the desired (and hopelessly unrealistic) level of new tax revenue, so there are discussion about how to expand the scope of the directive – including a scheme to ensnare more jurisdictions into the cartel. This is a non-OECD issue, but rest assured it will be in the minds of all European representatives at the Singapore meeting.

5. Formula apportionment of business income

Proponents of tax harmonization would like all nations to impose identical tax regimes. Such an approach would, by definition, eliminate tax competition and give politicians from all nations a common ability to increase tax rates. And it is the logical end point for proponents of the CEN theory. A direct attack on fiscal sovereignty is not plausible in the current environment, however, so advocates hope to gain a partial victory by harmonizing the tax base (i.e., the definition of taxable income) and then dividing up a company’s profits based on some sort of formula based on sales, employment, and/or assets. The European Commission is pushing for such an approach (the common consolidated corporate tax base), and many of the left are urging that this system be imposed on a global basis. The motive for this approach is that companies earn a “disproportionately” large share of their profits in low-tax jurisdictions. But if there was some sort of harmonized tax base, perhaps imposed in a might-makes-right fashion by big nations, then a formula could be used that would unilaterally turn profits earned in so-called tax havens (as well as places such as Hong Kong, Switzerland, Ireland, Slovakia, and China) into taxable income for Germany, France, Japan, and the United States. This would dramatically undermine incentives to invest in jurisdictions with better tax policy and lead to a significant increase in the corporate tax burden.

6. Worldwide taxation

Worldwide taxation refers to the practice of nations taxing things that occur outside their borders, and the United States has the worst worldwide tax system of any nation. Most jurisdictions at least attempt to impose double taxation on individual capital income (dividends, interest, and capital gains) on a worldwide basis, and the United States certainly is in this category. But the United States is an outlier in that it imposes worldwide taxation on corporate income. And it is virtually alone in taxing the labor income of citizens who live and work abroad. Indeed, the United States actually restricts the right of emigration, imposing punitive exit taxes (disgracefully reminiscent of the policies of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia) on people who want tax residency in other jurisdictions. Other nations rely much more on territorial taxation, but not because of an affinity for good tax policy or respect for human rights. Instead, their tax authorities don’t have the long reach and unchecked power of the IRS. But as privacy gets eroded and it becomes easier for other nations to track economic activity across the globe, the temptation will grow to copy America’s bad approach. Politicians from high-tax nations would love to retain taxing power over companies and individuals that move to places such as Hong Kong, Switzerland, Cayman, Panama, Monaco, Singapore, etc. If they succeed, this would dramatically reduce incentives to move to jurisdictions with better tax law and (because of the crippling impact on tax competition) facilitate big increases in tax rates.

It is impossible to say which, if any, of these proposals will be discussed at the Singapore Global Forum. With any luck, none of these issues will get on the agenda. But that is just a matter of timing. Sooner or later, politicians from high-tax nations will pursue some or all of these policies. And since the OECD is a tool of those high-tax nations, it is quite likely that a Global Forum will be the vehicle for continued assaults on tax competition, fiscal sovereignty, and financial privacy.

What should low-tax jurisdictions do?

Prior to the 2008 election, the American government had a policy of benign neglect regarding the OECD’s anti-tax competition project. This was very helpful. After all, just as OPEC would be feeble without the participation of Saudi Arabia, a global tax needs U.S. support. Ever since the 2008 elections, however, the United States government has been aligned with Europe’s welfare states. This unfortunate development largely explains why the OECD was able to go back on offense and coerce low-tax jurisdictions into agreeing to upon-request TIEAs.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that the Obama Administration is on the verge of a sweeping repudiation in the mid-term elections. Republicans almost certainly will win control of the House of Representatives. And the White House’s statist policies are so unpopular that it’s even possible that the Senate may switch to the GOP (something that almost certainly will happen in 2012 anyway because of which seats will be in play that year).

This has important implications for the tax competition battle. The Coalition for Tax Competition, led by the Center for Freedom and Prosperity and comprised of various taxpayer organizations, think tanks, and free market groups, intends to make a much more concerted effort to reduce the huge subsidy that American taxpayers provide to the OECD. And because of the backlash among voters against excessive government spending, and because Republicans feel they have to prove that they “got the message” after losing the last two elections because they had become big spenders during the Bush years, there will be a very receptive climate for the Coalition’s anti-OECD message.

So what will this mean? The OECD is like every other government bureaucracy. The first imperative is more money and more staff. And OECD bureaucrats know they have a very comfortable scam. Not only do they receive above-market compensation, but they also are exempt from paying any tax on their overly-generous incomes (yes, it goes without saying that it is ironic that tax-free bureaucrats get to jet-set around the world seeking to raise taxes on everybody else).

If Republicans take control of the House of Representatives (and even more so if they also win the Senate), it then becomes an open question whether the OECD is able to maintain an aggressive anti-tax competition campaign. There will be direct and indirect pressure to ease up on the big-government agenda. Other divisions of the Paris-based bureaucracy, for instance, will understand that their gravy train may get derailed because of the actions of the Committee on Fiscal Affairs, so there will be significant internal pressure to be more rational.

From the perspective of low-tax jurisdictions, it means that the OECD and high-tax nations should not be allowed to ram through any new initiatives. The clock is not on their side, so it is imperative to block the OECD from any schemes designed to accelerate the process. There will then be an opportunity to reassess after the American elections.

Fighting for Prosperity and Opportunity

Part of the OECD’s strategy has been to imply that low-tax jurisdictions are rogue regimes that somehow threaten the global economy. This is why they have striven to make “tax haven” a negative term. And remember when politicians from high-tax nations asserted the financial crisis somehow was caused by “hot money” from tax havens? Even gullible journalists quickly realized that was an absurd assertion.

It’s time to regain the offensive. The high-tax nations are the rogue regimes. They are the nations with unsustainable fiscal policy. Places such as Greece, Spain, Italy, and France are examples of high-tax nations that will destabilize the world economy by causing sovereign debt crises. OECD nations are the ones with punitive tax systems that undermine growth.

Tax havens and other low-tax jurisdictions are outposts of fiscal sanity – at least relatively speaking. Yes, they periodically fall into bad habits and let government get too big and spend too much, but at least they’re subject to the discipline of global markets and can’t bury their heads in the sand and cross their fingers that big new sources of revenue will be magically forthcoming.

The world would be a much better place if OECD nations copied the fiscal policy of tax havens, not vice versa.

Tax competition means better policy

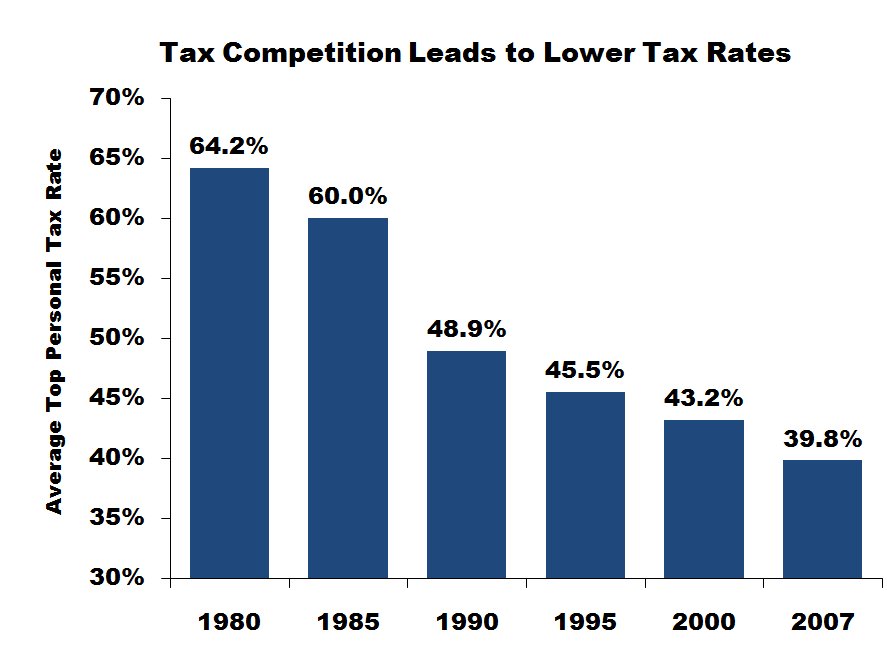

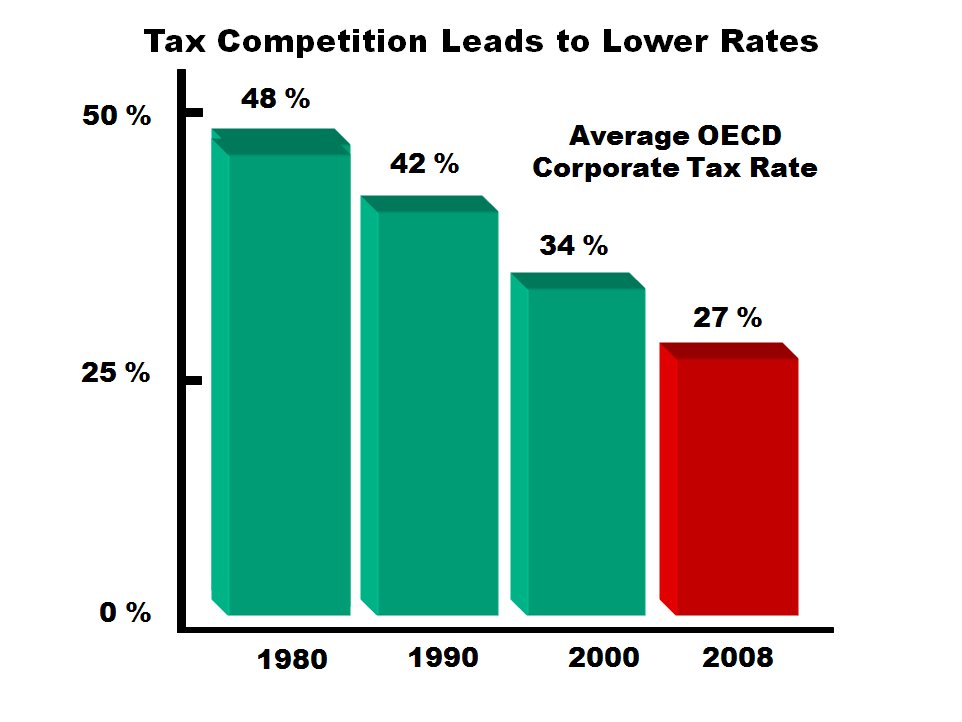

Low-tax jurisdictions generally are the ones with good tax policy. There is wide agreement among public finance economists that an ideal tax system should be based on low tax rates, no double taxation, no loopholes, and territoriality. Yet the OECD’s anti-tax competition effort is designed to help high-tax nations impose double taxation on an extraterritorial (or worldwide) basis.

This is why economists tend to be strong supporters of competition between jurisdictions. Tax competition encourages nations to adopt good tax policy, even if politicians from those countries would prefer to adopt class-warfare policies because of perceived short-run electoral considerations.

Rather than reiterate the main points in a conclusion, the best way to end this paper is with a series of quotes from Nobel laureates. These economists understand that a cartel of high-tax nations would be a mistake. An “OPEC for politicians” would hurt the global economy and condemn people around the world to a more dismal future.

“…competition among nations tends to produce a race to the top rather than to the bottom by limiting the ability of powerful and voracious groups and politicians in each nation to impose their will at the expense of the interests of the vast majority of their populations.”

Gary Becker

“…tax competition among separate units…is an objective to be sought in its own right.”

James Buchanan

“Competition among national governments in the public services they provide and in the taxes they impose is every bit as productive as competition among individuals or enterprises in the goods and services they offer for sale and the prices at which they offer them.”

Milton Friedman

“…international competition provided a powerful incentive for other countries to adapt their institutional structures to provide equal incentives for economic growth and the spread of the ‘industrial revolution.’”

Douglas North

“Competition among communities offers not obstacles but opportunities to various communities to choose the type and scale of government functions they wish.”

George Stigler

“[Tax competition] is a very good thing. …Competition in all forms of government policy is important. That is really the great strength of globalization …tending to force change on the part of the countries that have higher tax and also regulatory and other policies than some of the more innovative countries. …The way to get revenue is doing all you can to encourage growth and wealth creation and then that gives you more income to tax at the lower rate down the road.”

Vernon Smith

“With apologies to Adam Smith, it’s fair to say that politicians of like mind seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise taxes. This is why international bureaucracies should not be allowed to create tax cartels, which benefit governments at the expense of the people.”

Ed Prescott

“[I]t’s kind of a shame that there seems to be developing a kind of tendency for Western Europe to envelope Eastern Europe and require of Eastern Europe that they adopt the same economic institutions and regulations and everything. …We want to have some role models… If all these countries to the East are brought in and homogenized with the Western European members then that opportunity will be lost.

Edmund Phelps

__________________________________

Daniel Mitchell is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute (www.cato.org), a free-market think tank located in Washington, DC. He also co-founded the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation and serves as the Chairman of its Board of Directors.

The Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization operating under Section 501(C)(3). It is privately supported, and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

The Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation, the research and educational affiliate of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity (CF&P), can be reached by calling 202-285-0244 or visiting our web site at www.freedomandprosperity.org.

_______________________________________________

Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation

P.O. Box 10882

Alexandria, Virginia 22310-9998

Phone: 202-285-0244

info@freedomandprosperity.org

www.freedomandprosperity.org