April 2018, Vol. XII, Issue I

The European Bank for

Reconstruction and Development:

Cronyism and Corruption Instead of Growth

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development was created in 1990 to help former Soviet-Bloc nations make the transition from communism. The ostensible mission of this multilateral development bank, which began operations in 1991, is “furthering progress towards market-oriented economies and the promotion of private and entrepreneurial initiative.”

While these are very admirable goals, the EBRD has been ineffective, perhaps even counterproductive. There is no evidence that its policies have generated additional growth. Indeed, it is highly likely that the EBRD undermines prosperity since much of its operations are based on cronyism, with bureaucrats providing special privileges to politically connected private companies – thus politicizing the allocation of capital, undermining competitive markets, and fomenting corruption.

Given the dismal track record of other international bureaucracies, as well as the systemic failure of foreign aid to produce better economic performance, it’s unclear whether any reforms could salvage the EBRD.

By Daniel J. Mitchell

Introduction

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) started operations in 1991 with a primary goal of helping promote economic development in nations that had been part of the former Soviet Bloc. Most of the original donor nations were from Western Europe, though a handful of other nations such as the United States and Australia also were inaugural supporters of the ERBD.

Donors at the time committed the equivalent of 10 billion euros to the EBRD in order “to foster the transition towards open market‑oriented economies and to promote private and entrepreneurial initiative in the Central and Eastern European countries committed to and applying the principles of multiparty democracy, pluralism and market economics.”[1]

Structurally, the ERBD is a regional multilateral development bank, similar to the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank. Like other multilateral development banks, the EBRD is supposed to be self-sustaining. Some would even say profitable. But this is somewhat misleading since “…MDBs receive subsidies from their shareholders in the form of subsidised capital and tax exemptions and from their borrowers in the form of their preferred creditor status.”[2]

In any event, there is a difference between the ERBD and other MDBs. The creators of the EBRD decided to follow an unconventional path. Instead of helping to finance government projects such as infrastructure, which would be a typical activity of the other regional development banks, the EBRD “was given a mandate to finance investments, mostly in the private sector.”[3]

The important issue that will be addressed in this report is whether the EBRD has been successful in its core mission of promoting economic developing in post-Soviet economies. Unfortunately, an analysis of the actions of this comparatively new international bureaucracy indicates that it hinders rather than enables market-friendly reforms in transition economies.

Key Finding – Wrong Approach, Ineffective Results

The EBRD was created with the best of intentions. The collapse of communism was an unprecedented and largely unexpected event, and policymakers wanted to encourage and facilitate a shift to markets and democracy. A successful transition was seen as good for people in former Soviet-Bloc countries, of course, but it also was viewed as a smart investment on behalf of taxpayers in western nations.

But good intentions don’t necessarily mean good results. Especially when the core premise was that growth somehow would be stimulated and enabled by the creation of another multilateral government bureaucracy. There already had been numerous post-World War II initiatives – the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, national foreign-aid programs, etc – that were based on the notion that government intervention somehow could create growth in less-developed parts of the world.

These initiatives did not work.[4] Simply stated, nations grow if local politicians adopt the right policies. And that growth occurs even if there’s not one penny of aid. But if they impose the wrong policies, their economies will remain stagnant, regardless of how much aid they receive. This is known as the “Foreign Aid Paradox.”[5]

If poor nations want better economic performance, there is a recipe for growth and prosperity. It involves small government, free markets, and non-intervention. Here are the five major indices associated with growth, based on Economic Freedom of the World, an annual index published by Canada’s Fraser Institute.[6]

If poor nations want better economic performance, there is a recipe for growth and prosperity. It involves small government, free markets, and non-intervention. Here are the five major indices associated with growth, based on Economic Freedom of the World, an annual index published by Canada’s Fraser Institute.[6]

- Size of government – a measure of the fiscal burden of taxes and spending.

- Legal system and property rights – a measure of the quality and honesty of the rule of law.

- Sound money – a measure of monetary stability and open capital markets.

- Freedom to trade internationally – a measure of barriers to global markets.

- Regulation – a measure of red tape in credit markets, labor markets, and business operations.

Incidentally, the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom[7] and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report[8] also measure the quality of government policy based on similar indices. And they get very similar results. The bottom line is that outsiders can’t produce growth in a developing or transition nation unless they somehow have the power to coerce good policy.

At the risk of understatement, that’s not how multilateral development banks such as the EBRD or other global bureaucracies operate. At best, the EBRD and other aid providers can use moral suasion to encourage good policy. But in practice, aid providers rarely do even that.

Development experts openly admit that outside governments and bureaucracies are ineffective.

- Professor William Easterly, now at New York University after many years at the World Bank, sagely observed that, “The West’s efforts…have been even less successful at goals such as promoting rapid economic growth, changes in government economic policy to facilitate markets, or promotion of honest and democratic government. …Economic development happens, not through aid, but through the homegrown efforts of entrepreneurs and social and political reformers.”[9]

- Peter Bauer, a development economist and winner of the 2002 Milton Friedman Prize, cynically observed that foreign aid was basically “an excellent method for transferring money from poor people in rich countries to rich people in poor countries.”[10]

- Dambisa Moyo, writing about her home continent, grimly noted that, “The most obvious criticism of aid is its links to rampant corruption. Aid flows destined to help the average African end up supporting bloated bureaucracies in the form of the poor-country governments and donor-funded non-governmental organizations. …A constant stream of “free” money is a perfect way to keep an inefficient or simply bad government in power.”[11]

Unfortunately, even though its founding documents pay homage to markets and even though the webpage today contains similar rhetoric, there’s nothing in the track record of the EBRD that indicates it has learned from pro-intervention and pro-statism mistakes made by older international aid organizations. Indeed, there’s no positive track record whatsoever.

- There is no evidence that nations receiving subsidies and other forms of assistance grow faster than similar nations that don’t get aid from the EBRD.

- There is no evidence that nations receiving subsidies and other forms of assistance enjoy more job creation than similar nations that don’t get aid from the EBRD,

- There is no evidence that nations receiving subsidies and other forms of assistance have better social outcomes than similar nations that don’t get aid from the EBRD.

Problems

Let’s review some of the specific shortcomings and mistakes of the EBRD. We’ll look at both design flaws and operational flaws.

Capital Misallocation

A “macro” problem that is common to all multilateral development banks, as well as other international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, is that the decisions of these bureaucracies distort the allocation of capital.

In a normal economy, savers, investors, intermediaries, entrepreneurs, and others make decisions on what projects get funded and what businesses attract investment. These private-sector participants have “skin in the game” and relentlessly seek to balance risk and reward. Wise decisions are rewarded by profit, which often is a signal for additional investment to help satisfy consumer desires.

There’s also an incentive to quickly disengage from failing projects and investments that don’t produce goods and services valued by consumers. Profit and loss are an effective feedback mechanism to ensure that resources are constantly being reshuffled in ways that produce the most prosperity for people.

The EBRD interferes with that process. Every euro it allocates necessarily diverts capital from more optimal uses. Defenders of the status quo argue that the EBRD fulfills an important role by supplying capital to underserved regions. But this is wrong on two levels.

- Good investments would not need subsidized capital, particularly is a world awash in capital seeking profitable opportunities.

- If investments in a certain region are not attractive, that means one of two things.

- It would be a waste of money to divert capital to that region.

- There are policy barriers to capital that local governments should fix.

Cronyism

A “micro” problem is that the EBRD is in the business of “picking winners and losers.” This means that intervention by the bureaucracy necessarily distorts competitive markets. Any firm that gets money from the EBRD is going to have a significant advantage over rival companies. Preferential financing for hand-picked firms from the EBRD also is a way of deterring new companies from getting started since there is not a level playing field or honest competition.

As the Economist observed, “…for the past 20 years, from Malaysia to Mexico, crony capitalists—individuals who earn their riches thanks to their chumminess with government—have had a golden era” and “Industries that have a lot of interaction with the state are vulnerable to crony capitalism.”[12]

And Matt Ridley, writing for the U.K.-based Times, warned, “Continuing prosperity depends on…what the economist Joseph Schumpeter called creative destruction. …there is ever more opportunity to live off “rents” from artificial scarcity created by government… businesses become embedded in government cronyism…heavily dependent on government contracts, favours or subsidies.”[13]

In other words, cronyism is a threat to prosperity. It means the playing field is unlevel and that those with political connections have an unfair advantage over those who compete fairly.

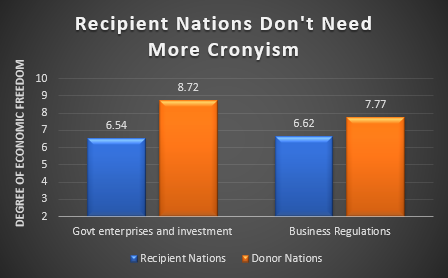

To make matters worse, nations that receive funds from the ERBD already get dismal scores from Economic Freedom of the World for the two subcategories (“government enterprises and investment” and “business regulations”) that presumably are the best proxies for cronyism.[14] This chart compares donor nations from Western Europe and the United States to recipient nations in the former Soviet Bloc. The gaps are substantial.

Given that recipient nations already have a severe problem with cronyism, is it remarkable that the EBRD is enabling and encouraging these bad policies. Especially when the donor nations – while far from perfect – have done a decent job of insulating their economies from cronyist policies.

Given that recipient nations already have a severe problem with cronyism, is it remarkable that the EBRD is enabling and encouraging these bad policies. Especially when the donor nations – while far from perfect – have done a decent job of insulating their economies from cronyist policies.

Some might argue that the EBRD’s track record of not losing money insulates it from the charge of cronyism.[15] But after-the-fact profitability is not a measure of success since subsidized capital can allow a firm to gain an undeserved advantage over competitors. In other words, it’s a sign of successful cronyism rather than successful governance.

Corruption

When governments have power to arbitrarily disburse large sums of money, that is a recipe for unsavory behavior. For all intents and purposes, the practice of cronyism is a prerequisite for corruption. The EBRD openly brags about the money it steers to private hands,[16] so is it any surprise that people will engage in dodgy behavior in order to turn those public funds into private loot?

For instance, a column in the EU Observer noted that, “EBRD money has ended up in the pockets of people associated closely with the authoritarian regime of President Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus, raising some doubts over the verification mechanisms in place at the bank to ensure the public money it disburses actually benefits ordinary people in its theatre of operations.”[17]

Another analysis found that, “in the EBRD’s projects, an increasing number of cases are becoming visible in which serious allegations of corruption do not seem to have had an impact on the EBRD’s stance towards the project or the company leading the projects.”[18]

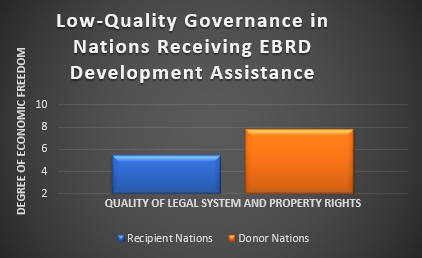

None of this should be a surprise. Recipient nations get comparatively poor scores for “legal system and property rights” from Economic Freedom of the World. They also do relatively poorly when looking at the World Bank’s “governance indicators.”[19] And they also have disappointing numbers from Transparency International’s “corruption perceptions index.”[20]

So, it’s no surprise that monies ostensibly disbursed for the purpose of development assistance wind up lining the pockets of corrupt insiders. For all intents and purposes, the EBRD and other dispensers of aid enable and sustain patterns of corruption.

Ironically, even the EBRD’s own research indicates that government facilitates and enables corruption. A working paper from 2015 found that “…unexpected financial windfalls increase corruption in local government. … Our results imply that a 10 per cent increase in the per capita amount of disbursed funds leads to a 12.2 per cent increase in corruption. …Our results highlight the governance pitfalls of…assistance from international organisations.”[21]

Ironically, even the EBRD’s own research indicates that government facilitates and enables corruption. A working paper from 2015 found that “…unexpected financial windfalls increase corruption in local government. … Our results imply that a 10 per cent increase in the per capita amount of disbursed funds leads to a 12.2 per cent increase in corruption. …Our results highlight the governance pitfalls of…assistance from international organisations.”[21]

Leftward Drift

Like many multilateral organizations, the EBRD advocates policies that would increase the power of the state relative to the private economy. In the case of the EBRD, however, these statist policies are directly contrary to the ostensible pro-market mission of the bureaucracy.

Consider the EBRD’s 2016-17 transition report, for instance, which embraced destructive capital taxes.

Taxing wealth…may be an effective method of fiscal redistribution, as well as a means of raising additional revenue. Taxes on inheritance, in particular, tend to be less distortionary, in the sense that they affect people’s level of effort or employment decisions to a lesser extent.[22]

This is remarkably shoddy economic analysis. Taxing wealth and inheritances may not have a big impact of incentives to provide labor, but such policies surely have a major impact on incentives to provide capital. And since all economic theories, even socialism and Marxism, agree that capital accumulation is a vital prerequisite for economic growth, rising living standards, and higher wages, punitive taxes on saving and investment are especially destructive.

The transition report also veers into class warfare by expressing support for higher taxes and bigger government.

Tackling broader inequality requires…redistribution through taxation and public spending.[23]

To be fair, the report does note that inequality is not necessarily bad. Moreover, it draws a distinction between earned wealth and cronyism-generated wealth. That insight suggests that there should be a very aggressive campaign to stamp out government favoritism, but the EBRD appears to be somewhat muted on this topic – perhaps because one of its core functions is diverting capital to favored companies and industries.

Even when the EBRD identifies a genuinely important issue, there is an unwillingness to propose real solutions. For instance, the report highlights the importance of education to promote equality of opportunity, yet there is no discussion of pro-market reforms such as school choice that would deliver better results for less money.

Another example is that the 2016-17 transition report has an entire chapter on “financial inclusion” and the extent to which low-income people can access and benefit from the banking system. And that chapter specifically notes that “A lack of documentation is…an issue for the young” and that “Documentation requirements may have a particular impact on workers in the informal sector and the self-employed.” Yet there is only very weak and indirect criticism of the “money-laundering laws” that impose high costs on financial firms and specifically make financial services too expensive for poor people.

The 2017-18 transition report is not quite so slanted, but it has a chapter on “Green Growth” which is based on the illogical premise that relatively poor economies can benefit from utilizing more expensive forms of energy. The EBRD could have been honest and put forth an argument that it is necessary and desirable to sacrifice growth to achieve ostensible environmental benefits. Instead, it decided to promote the economic version of a perpetual motion machine.[24]

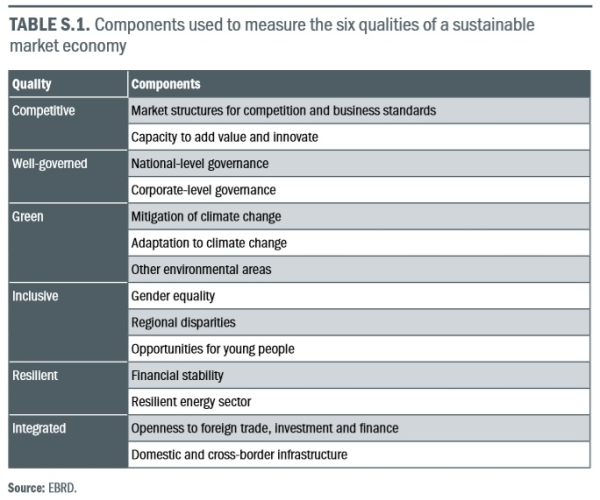

The EBRD’s muddled approach to economics is captured in the components used to measure a “sustainable” market economy, which confuses means and ends. Components such as “capacity to add value and innovate” are merely descriptions of a competitive economy. And “well-governed” certainly is a good trait for both the public sector and corporate sector. But those are ends. What about means? Table S.1. lists some positive policies such as open trade and capital markets, but it also lists “climate change” and “gender equality,” which easily could be excuses for anti-market interventions by governments.

For all intents and purposes, it appears the EBRD now openly rejects its original mission, openly disputes the notion that markets are the engine for growth and prosperity.

For all intents and purposes, it appears the EBRD now openly rejects its original mission, openly disputes the notion that markets are the engine for growth and prosperity.

Views on the roles of the state and the private sector have also evolved since the start of the transition process. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the prevailing economic thinking was that the economic role of the state should be limited… More recently, however, it has increasingly been recognised – particularly after the 2008-09 financial crisis – that unfettered markets…can lead to suboptimal outcomes such as rising inequality… The slow growth that has been observed in the aftermath of the financial crisis – especially the high unemployment rates and the weak growth in real incomes – has contributed, in some countries, to public disillusionment with markets and a decline in public support for market reforms.[25]

This is not the mentality of a bureaucracy that is going to help nations shrink the size and scope of government.

Additional problems

There are other concerns about the EBRD.

- Bad fiscal policy and/or lack of good fiscal policy – Like many international bureaucracies, the EBRD almost always says the right thing on trade policy. And the EBRD usually is reasonably sensible on regulatory policy (with “climate” being a notable exception). But the bureaucracy is AWOL – at best – on fiscal policy. The EBRD’s transition indicators, for instance, could be greatly strengthened by including taxation (overall burden, marginal tax rates, tax complexity, etc). Even the World Bank includes such measures in Doing Business.[26]

- Duplication and mission creep – It’s unclear why the EBRD was created since it fulfills (at least in theory) the same mission as the World Bank. Was there really a need for another bureaucracy? The EBRD’s bureaucrats would say yes, naturally, since they get lavish salaries that are exempt from national taxation.[27] That’s good for them, but that doesn’t change the fact that there’s no evidence that the EBRD improves growth in recipient nations. Yet that isn’t stopping the bureaucracy from expanding. Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, and Lebanon were never part of the Soviet Bloc, yet they are now getting subsidies from the EBRD.[28]

- Whither Democracy? – The founding documents of the EBRD and the current website laud “multi-party democracy” and “pluralism”, and for good reason. Indeed, the EBRD ostensibly is only supposed to help nations satisfying those criteria.[29] Yet the bureaucracy is diverting capital to several governments that are ranked as “not free” by Freedom House. Indeed, both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are ranked about being among the world’s 10-most repressive governments.[30]

Conclusion

The EBRD has a noble-sounding mission. But good intentions and lofty rhetoric don’t produce economic growth, higher living standards, and better outcomes.

The EBRD is a duplicative bureaucracy that was created under the dubious premise that a new multilateral institution could somehow boost economic performance notwithstanding the dismal track record of foreign aid.

Even more troubling, the EBRD has chosen to operate as a cronyist organizations, distorting the allocation of capital and undermining competitive markets by providing preferential funds to politically well-connected firms.

The only identifiable beneficiaries of the EBRD, other than favored companies, are the bureaucrats. That’s not a worthwhile legacy.

__________________________________

Daniel J. Mitchell is a co-founder of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation and serves as the Chairman of its Board of Directors.

The Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization operating under Section 501(C)(3). It is privately supported and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

_______________________________________________

Endnotes

[1] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Basic Documents of the EBRD,” September 30, 2013. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/institutional-documents/basic-documents-of-the-ebrd.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Willem Buiter and Steven Fries, “What should the multilateral development banks do?”, Working Paper No. 74, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, June 2002. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/economics/workingpapers/wp0074.pdf.

[4] Dženan Đonlagić and Amra Kožarić, 2010. “Justification Of Criticism Of The International Financial Institutions,” Economic Annals, Faculty of Economics, University of Belgrade, vol. 55(186), pages 115-132.

[5] Daniel J. Mitchell, “The Foreign Aid Paradox,” International Liberty, October 31, 2016. Available at https://danieljmitchell.wordpress.com/2016/10/31/the-foreign-aid-paradox/.

[6] James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, and others, Economic Freedom of the World, Fraser Institute, September 28, 2017. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2017-annual-report.

[7] Terry Miller, Anthony B. Kim, and James M. Roberts, 2018 Index of Economic Freedom, Heritage Foundation, January 2018. Available at https://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2018/book/index_2018.pdf.

[8] Klaus Schwab, ed, Global Competitiveness Report, 2017-2018, World Economic Forum, 2017. Available at http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2017-2018/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2017%E2%80%932018.pdf.

[9] William Easterly, “Why Aid Doesn’t Work,” Cato Unbound, April 2, 2006. Available at https://www.cato-unbound.org/2006/04/02/william-easterly/why-doesnt-aid-work.

[10] The Economist, “A Voice for the Poor,” May 2, 2002. Available at https://www.economist.com/node/1109786.

[11] Dambisa Moyo, “Why Foreign Aid Is Hurting Africa,” Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2009. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB123758895999200083.

[12] Economist, “Comparing crony capitalism around the world,” May 5, 2016. Available at https://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2016/05/daily-chart-2.

[13] Matt Ridley, “Cautious crony organizations stifle innovation,” Times, April 9, 2018. Available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/comment/cautious-crony-organisations-stifle-innovation-0bswjhk8p.

[14] Economic Freedom of the World, “Dataset,” 2017. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/economic-freedom/dataset?geozone=world&year=2015&page=dataset&filter=1&min-year=2&max-year=0.

[15] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “2016 in Numbers,” (accessed April 10, 2018). Available at http://2016.ar-ebrd.com/in-numbers/.

[16] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Stories,” (accessed April 10, 2018).. Available at http://2016.ar-ebrd.com/category/our-stories/.

[17] Ionut Apostol, “Lessons Learned for the EBRD,” EU Observer, April 10, 2012. Available at https://euobserver.com/opinion/115831.

[18] CEE Bankwatch Network “Coal and corruption – the case of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development,” December 2013. Available at https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/EBRD-coal-corruption.pdf.

[19] World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, (accessed April 10, 2018). Available at http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=worldwide-governance-indicators.

[20] Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index, 2017, February 21, 2018. Available at https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017.

[21] Elena Nikolova and Nikolay Marinov, “Do public fund windfalls increase corruption? Evidence from a natural disaster,” Working Paper No. 179, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, April 2015. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/documents/oce/do-public-fund-windfalls-increase-corruption-evidence-from-a-natural-disaster.pdf.

[22] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Transition Report 2016-17”, November 4, 2016. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/transition-report/transition-report-201617.html.

[23] Ibid.

[24] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Transition Report 2017-18,” November 22, 2017. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/transition-report-2017-18.

[25] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Transition Report 2017-18,” November 22, 2017. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/transition-report-2017-18.

[26] World Bank, Doing Business: Reforming to Create Jobs, October 31, 2017. Available at http://www.doingbusiness.org/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2018.

[27] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Basic Documents of the EBRD,” September 30, 2013. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/institutional-documents/basic-documents-of-the-ebrd.html.

[28] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Where We Are,” accessed April 9, 2018. Available at http://www.ebrd.com/where-we-are.html.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Freedom House, “Freedom in the World, 2018,” January 16, 2018. Available at https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2018.