August 2018, Vol. XII, Issue III

Fiscal Crisis in America, Part 2:

Greece – A Harbinger for the United States?

By Sven R. Larson*

A fiscal crisis in the United States is no longer unthinkable. It is difficult to assess the probability and the exact timing of a crisis; to do so would require large sets of data from similar events in the past. Since fiscal crises have been unusual historically, traditional economic analysis is of little help here. However, the fiscal crisis in Greece that began ten years ago is a compelling case study for what the United States could be looking forward to. There are compelling similarities between the macroeconomic and fiscal situations in Greece before the crisis and in the United States today.

The Greek crisis became global news in 2010 when the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund formed what has since become known as the “Austerity Troika” or, for short, the “Troika”. In response to fading debt-market investor confidence in Greek treasury bonds, the Troika intervened to coordinate lending to the Greek government, bring borrowing costs under control and stem the tide of surging interest rates.

In return, the Greeks would have to accept tough fiscal measures designed to quickly bring down the deficit. Initially, in February 2010 when the first austerity package was announced, the implication was that one such package would be enough to bring the Greek fiscal crisis under control. That would have been a tall order to fill: in January that year, Greek treasury bonds had come under “ferocious pressure” in response to a budget deficit of almost 13 percent of GDP.[1]

Since 2010, the Troika has subjected Greece to approximately one dozen austerity packages (depending on how one technically separates the packages) and although the intensity in austerity policies has decreased, to date there is no guarantee that the crisis is over. At no point has either the Troika or the government in Athens explained why previous austerity measures have not been enough to solve the fiscal crisis, or why more of the same fiscal medicine would have a different effect than than previous packages.

As the budget finally balances in 2018, the Greek nation has paid a hefty price for eight years of fiscal crisis measures:

- Gross Domestic Product fell by one quarter in current prices;

- Youth unemployment topped out at 60 percent in 2013, subsequently stabilizing around 50 percent;

- The average Greek family has lost 38 cents of every euro they made before the crisis;

- One fifth of government spending is gone, yet taxes have increased from 39 percent of GDP to 50 percent.

This tally is not indicative of any specific outcome of a U.S. fiscal crisis. However, it is important to note that when the Greek crisis broke out, there were no forecasts to be found that would come even close to predicting just how serious the situation would become. Therefore, the similarities between pre-crisis Greece and the United States, together with this tally, suggest that the U.S. economy could pay a literally unimaginable price if it fell into a fiscal crisis.

Spending is the problem in Greece – and in the United States

Economists often point to growth as a remedy for structural problems in the economy. There are good reasons for this, as explained by Dan Mitchell in a 2014 article in the Wall Street Journal.[2] Growth allows poor and low-income families to find better-paying jobs; it increases demand for high-paid workers, thus motivating people to improve their labor market skills; it opens new, profitable opportunities for entrepreneurs and rewards risk taking.

All in all, economic growth lifts people out of dependency on government. This should mean that government spending would be less of a problem in economies with strong growth. Specifically, strong growth should allow governments to collect more than enough taxes to pay for whatever spending is essential over the long term.

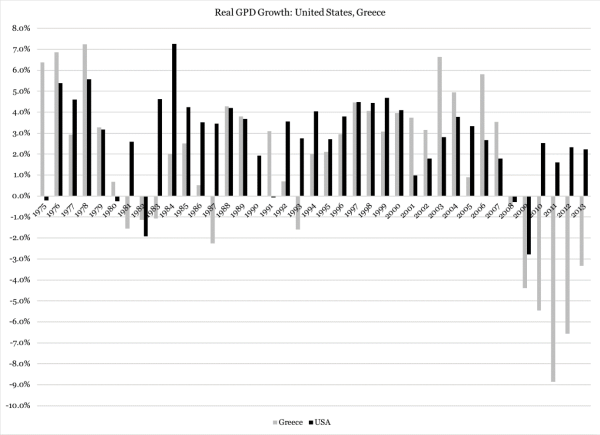

Since the Greek fiscal crisis erupted after a long streak of budget deficits, it is reasonable to ask whether the country’s economy had suffered from slow growth. As Figure 1 explains, that is not the case – on the contrary, over the past few decades, Greece has been able to match the United States in GDP growth:

Figure 1

Source: United Nations National Accounts Database

It was not for lack of economic growth that the Greek economy fell into a fiscal crisis. Notably, both the Greek and the U.S. economies saw growth rates in the 2-3 percent range as recently as in the 2000s (with the Greek GDP occasionally expanding much faster). By any reasonable account, both countries should have been able to feed their governments with enough tax revenue to maintain balanced budgets.

With relatively strong growth, both the Greek and the U.S. economies could grow tax revenue at more than adequate rates. In Greece, during the ten years immediately before the crisis began in 2008, total tax revenue grew by more than seven percent per year. In current prices, tax revenue more than doubled from 1996 to 2006.

The U.S. government saw its revenue grow almost as fast: from 1988 to 2007, federal tax revenue expanded by 5.8 percent per year on average. In 2005 and 2006, revenue growth reached 14.5 percent and 11.8 percent, respectively.

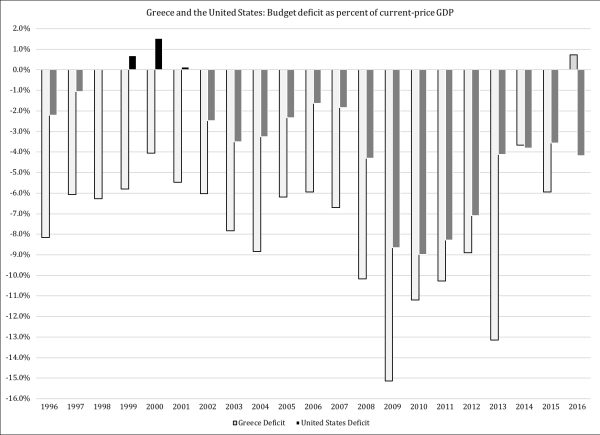

Despite rapid expansion in tax collections, neither country’s government was able to pay for its spending:

Figure 2

Source: Eurostat

There is no other way to characterize the lead-up to the Greek crisis than as a virtually chronic problem with excess government spending. For this reason, it is worth taking seriously the similarities between Greece and the United States.

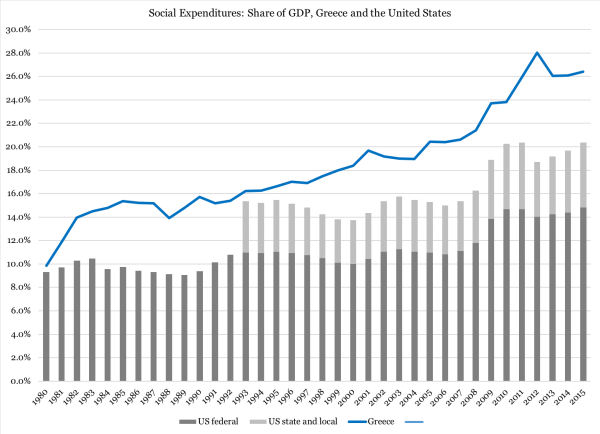

To reinforce this parallel, Figure 3 reports growth rates in so-called social expenditures, or what is known in American parlance as “entitlements”. In both countries, this form of government spending has grown as share of current-price GDP:

Figure 3*

Source: Eurostat (Greece); Office of Management and Budget (U.S. federal); Census Bureau (U.S. State and Local)

The steady growth in social expenditures explains why healthy growth rates in GDP cannot yield enough tax revenue to pay for all of government outlays. The purpose of social expenditures is to redistribute income and consumption between citizens, the goal being a gradual diminution of economic differences between citizens.[3] In order to fulfill this goal, governments must gradually, over time, grow social expenditures as share of the economy. Therefore, the ideological foundation of government spending makes it inevitable that it grows over time and as share of GDP.

When government grows as share of GDP, by definition it creates a lasting need for higher taxes. A tax system with constant rates and a constant tax base will only grow tax revenue when GDP grows; tax revenue will remain a constant share of GDP. When spending grows faster than GDP, government will have to expand its taxation either by raising tax rates or by growing its tax base (or both). If tax hikes do not keep up with the expanding welfare state, the inevitable consequence is a growing government debt.

Similarities and differences

There are obvious limitations to a comparison between the Greek and the American economy. Greece has a GDP the size of Alabama, with an industrial structure that is a far cry from as diversified as the U.S. economy. Greece is also much more dependent on foreign trade.

At the same time, there are enough similarities to make a serious comparison worth the while. Both economies are subject to the same universal economic laws, such as the incentives and disincentives created by government participation in the economy. High taxes and generous entitlements have the same discouraging effects everywhere on investments, entrepreneurship and workforce participation.

As the social-expenditure data indicates, there are also important institutional similarities between the two countries. Government provides for retirement and poverty relief, gives cash and in-kind benefits to families with lower incomes, and funds their spending with taxes that disproportionately target higher incomes. Health care is under government hands to a larger extent in Greece than in the United States, but over the years the differences have become smaller.

With regard to government spending, the main difference is in the growth trend. Greek expenditures have grown continuously, while U.S. spending has jumped with recessions. There is a visible jump in federal social expenditures around 1980, in the wake of the second oil-price recession of the 1970s. During the Reagan presidency federal social expenditures dipped below ten percent of current-price GDP.

With the recession in the early 1990s the ratio for federal spending once again climbed above ten percent and has never been below that mark again. Not even the strong growth period in the late 1990s could bring the ratio down to Reagan-era levels.

The Millennium and Great Recessions bumped up the social expenditures ratio in two increments, such that it is now above 14 percent of GDP. There is even a hint of a rise in the past couple of years, right as the economy was recovering from the Obama-era recession and stagnation.

It is important to note that the American welfare state differs from most of its European peers in one important way: it splits its spending between three levels of government. States and local governments are responsible for social expenditures equal to approximately five percent of GDP, money that must be added to the federal outlays in order to give an accurate picture of just how big the American welfare state is.

While there is no one-stop database for welfare-state spending in the United States, the Census Bureau and the Office of Management and Budget produce data of comparable quality. When added together, these two forms of social expenditures are now at 20 percent of GDP; the U.S. levels of spending are not at contemporary Greek levels. However, it is worth noting that when the Great Recession began in 2008, Greek social expenditures were just a smidge above 20 percent of GDP.

The fact that U.S. social expenditures are now at “Greek” levels of ten years ago adds to the long-term growth trend in this spending category. While this does not place the United States at the doorstep of a fiscal crisis, it does suggest a dangerous level of fiscal vulnerability. The level of social expenditures reveals an irresponsible magnitude of entitlement promises. These promises, in turn, structurally exceed the levels that U.S. taxpayers can fund.

In lieu of substantial spending reform, the federal budget is returning to trillion-dollar deficits.[4] These forecasts do not take into account the budgetary effects of the next recession; a decline in tax revenue following a dip in macroeconomic activity could easily generate a deficit shockwave in the federal budget. Since most of the spending driving this deficit is of the entitlement kind, it is likely that any warning signals of a looming deficit shock will go unnoticed. This is yet another “Greek” parallel.

The fiscal crisis comes to Athens

The big, unanswered question is what a fiscal crisis could look like in the United States. Since our country has never experienced anything comparable to such a crisis, it is again relevant to draw on the experience from Greece.

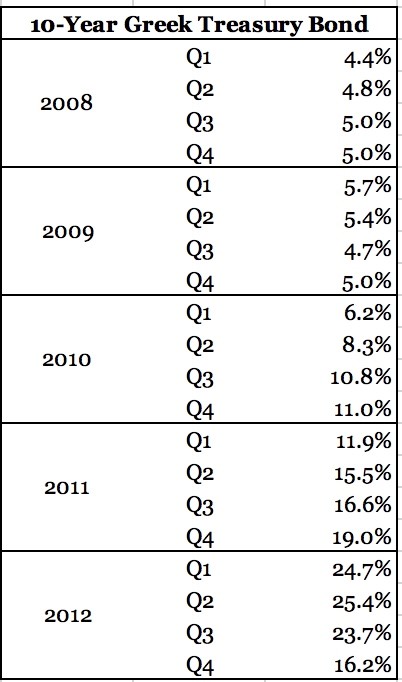

Once government debt and deficits were at a point where global debt-market investors lost confidence in the Greek economy, interest rates began rising. Initially the increase was moderate: the ten-year treasury bond rate rose from 3.4 percent in the third quarter of 2005 to five percent by the end of 2008. Then the increase accelerated:

Table 1

Source: European Central Bank

It is an open question whether or not such interest rates are possible in the United States. On the one hand, the European Central Bank quelled the spike by unleashing a bond-buying program that really was nothing more than a masked, and massive, deficit monetization program. This raises the possibility that the Federal Reserve could keep U.S. rates in check by copying the ECB strategy.

On the other hand, the Federal Reserve has already engaged in various forms of deficit monetization for approximately a decade. Its penchant for printing money gained global notoriety under the Bernanke era as “quantitative easing”. Since Janet Yellen’s chairmanship the Federal Reserve has been trying to distance itself from this era, ostensibly to rebuild some muscle in the event of new runaway budget deficits. However, that does not mean that the central bank would have anywhere near the credibility or even capability needed to neutralize a debt-market loss of confidence in the U.S. Treasury.

In other words: the responsible approach is to consider seriously the possibility that budget deficits at the trillion-dollar level will at some point be associated with a rapid, and rather violent, spike in interest rates.

If that happened, it would have serious effects on the federal budget. At the current (July 2018) approximate interest rate on U.S. debt of 2.75 percent, net interest payments are expected to reach $315 billion:

- If the rate doubled to 5.5 percent, the debt would cost taxpayers $41 billion more than Medicare;

- If the rate tripled to 8.25 percent, the debt would cost taxpayers more than Defense, Veterans Benefits and Transportation together;

- If the rate quadrupled eleven percent, the debt cost would by far be the biggest item in the federal budget, costing $1.25 for every $1 spent on Social Security.

The Greek ten-year bond rate did not peak until it had exceeded 25 percent. That peak, again, was reached only because of unprecedented intervention by the European Central Bank, the European Union and the International Monetary Fund.

There is no way of confidently estimating the risk of a U.S. interest-rate spike, let alone to suggest how Congress would react to it. However, even if the risk of quadrupled or even tripled interest rates is small, it is important to note that even smaller increases can have very serious effects on the federal budget, and force Congress into legislation that, today, would seem unthinkable.

Greece was forced by its unraveling debt situation to subject its government budget to repeated austerity packages. The practical meaning of these packages were a long series of rapid-fire spending cuts and tax hikes.

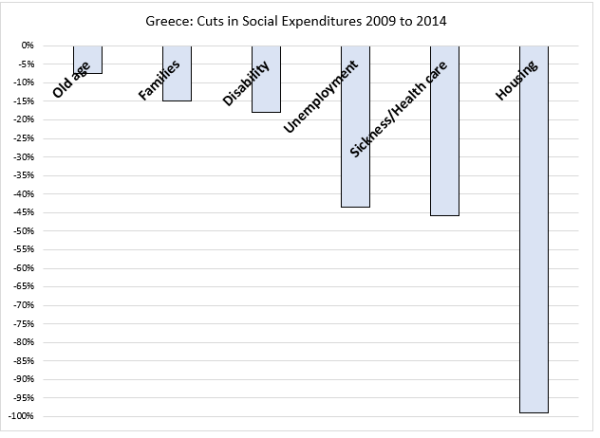

On the spending side, all categories of social expenditures took a beating:

Figure 4

Source: Eurostat

Some of the hardest-hitting reductions took place in unemployment benefits. From 2009 to 2014, total spending declined from 3.4 billion euros to 1.9 billion euros, in current prices. While not the largest cuts percentage-wise, the impact on an individual level was substantial, with a decline from 7,000 to 1,500 euros per year.

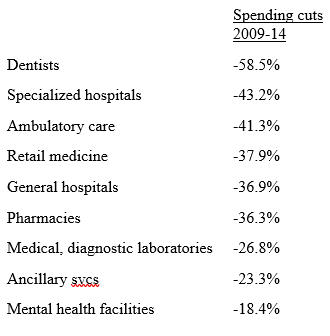

Tax-paid health care, a staple of the European welfare state, also took a hard beating. From 2009-2014, government reduced health care spending by 46 percent. Table 2 explains how government walked away from its promises to provide benefits practically across the entire health-care spectrum:[5]

Table 2

All these spending cuts represent partial or full-scale defaults on promises that the welfare state has made to its citizenry. When people are given a promise from government that they will be taken care of in the event of unemployment and other adverse experiences, they reduce their own contingency-based savings. Likewise, when government promises health care, housing subsidies and other entitlements, people place their standard of living above their means. Therefore, rapidly executed spending cuts have deeply negative effects on people’s personal finances in a way that predictable, gradual, long-term spending reductions do not.

As if to drive home the point about the difference between unpredictable spending cuts and reductions made in a predictable manner, the Greek government was perfectly able to bring its spending under control when they wanted to enter the euro zone (which they did in 2000). As part of its initiation rite, the Greek government had to at least look like they were trying to comply with the EU’s budget rules of a deficit at or below three percent of GDP and a debt no higher than 60 percent of GDP.

From 1996 to 2000, the Greek government managed to cut its deficit in half, from -8.2 percent of GDP to -4.1 percent.[6] Once the euro-zone membership was secured, deficits began increasing again. From 2001 through 2007, the deficit averaged -6.7 percent of GDP.

During the belt tightening leading up to the euro-zone entry, the Greek economy showed no visible signs of macroeconomic distress. The Greek government had time to implement spending restraint that would resonate with private-sector confidence. It is likely that if they had maintained this regime and gradually phased out the deficit, they could have avoided the fiscal crisis entirely.

Destructive tax hikes

Predictable deficit reduction means, in part, taking measures that avoid higher taxes. In fact, when spending cuts are done right they pave the way for future tax reductions. That, however, presupposes that the goal with reducing spending is to reduce the government’s fiscal footprint in the economy.

Policy measures in response to a fiscal crisis do not have the same purpose: they are dictated entirely by the need to mitigate a confidence meltdown among government creditors. Therefore, predictable policy measures are preventative and therefore proactive in helping a government avoid a fiscal crisis; once the crisis breaks out, there is only time for reactive, crisis-mitigating measures.

Due to the need to execute the highest amount of deficit reduction in the shortest time possible, crisis-ridden governments will resort to tax increases when they come with a smaller political price tag than spending cuts. For this reason, the macroeconomic repercussions of austerity in response to fiscal crises are always negative (Larson 2014). Greece is a case in point:

- in 2004, taxes tallied up to 38.8 percent of GDP

- in 2008, when the crisis started, they were 40.7 percent of GDP;

- in 2012, three years after the Troika had begun its reign in Athens, taxes suddenly claimed 46.5 percent of GDP;

- by 2016 they had gone up even further to 49.7 percent.

By 2012, GDP had declined by more than 19 percent. By 2016 it had fallen by a total of 25 percent, an almost unprecedented loss of economic activity in the modern, industrialized world.

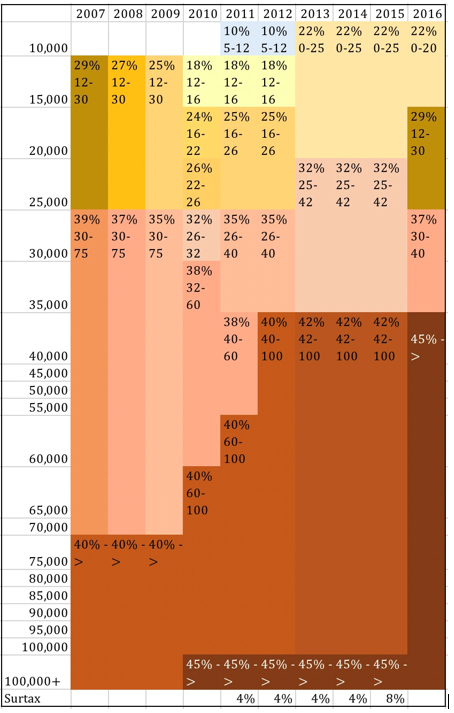

The causal relationship from higher taxes to declining GDP is easy to understand against the backdrop of multiple increases in income taxes. As Table A reports, prior to the first Troika-imposed austerity package in 2010, Greece was on a slow path toward tax relief, at least for low-income families. As mentioned earlier, the GDP growth record was strong before the crisis set in.

Starting in 2010, the Greek parliament raised income tax rates in several steps. One of many effects was the gradual extension of the the highest 45-percent tax bracket, from incomes above 100,000 euros down to 35,000 euros. However, all income layers saw taxes go up, often significantly:

Table 3

Source: OECD

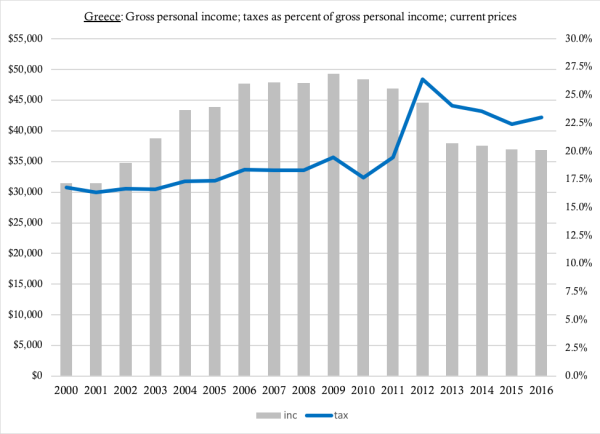

Figure 5 explains how sharp the effect of the income-tax increases actually was. It reports gross personal income for a family in Greece with approximately average incomes and the percentage of that income the family paid in taxes:

Figure 5

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Other taxes also increased, either in isolation or in combination with spending cuts:

- Another package in October 2011 raised taxes in multiple steps through 2014. Among the tax hikes were a “solidarity levy” on personal income, a cut of the standard income-tax deduction by more than half (from 12,000 euros to 5,000 euros), a substantial increase in the VAT for restaurants, a one-third hike in excise taxes on fuel, cigarettes and alcohol, to mention a few. These tax hikes were combined with reductions in government employee wages, the national defense budget, health care, income security, pensions, local governments and education (which led to the closing or merger of almost 2,000 schools).[7]

- By March 2012, new cuts in pensions, health care and defense spending were accompanied by large layoffs of government workers.[8] The cuts were accompanied by a slash to the country’s minimum wage, meant to slow the rise in unemployment.[9]

- In July 2013, BBC reported that corporate income-tax rates were going up, while low-earning farmers would lose their tax-exempt status.[10]

- In July 2015, CNBC reported on a “big hike” in Greek consumption taxes. The tax, which applied to both goods and services, increased from 13 percent to 23 percent. CNBC also reported that this incease in cost of living would take an extra 1,500 euros ($1,625) per year out of an average family budget.[11]

- Less than a year later, in May 2016, Reuters reported that the Greek parliament passed yet another increase in consumption taxes from 23 to 24 percent. This was “the sixth VAT hike in as many years” that “would depress sales by 3 percent, increase tax evasion”.[12]

- Also, in May 2016, The Guardian reported on “array of new levies, from a special import tax on coffee to extra duties on hotel bookings and a consumption tax on beer.”[13]

- January 2, 2017, Deutsche Welle explained that the Greek government yet again increased the value-added tax, adding “higher duties on tobacco products, coffee, and automotive fuels.”[14]

Multiple tax increases of such tangible proportions do double harm to the economy. The impact in terms of higher cost of living and of doing business is immediate and likely responsible for the brunt of the decline in the Greek economy. However, there is also the longer-term effect of increased uncertainty for both households and businesses. When taxes go up drastically and frequently, and when the tax hikes are announced on short notice as “emergency measures”, uncertainty spreads among economic decision makers. Consumers who can still afford to, will hoard as much cash as possible for future contingencies and refrain from taking on new spending commitments such as a car loan or a second mortgage. Business owners will make short-sighted but critically necessary decisions to maintain or increase their operating margins in an effort to be prepared when the next tax hike comes.

When consumers and businesses become short-sighted in their decision making, it has a negative effect on long-term economic activity. By injecting uncertainty into the private sector, government derelicts on one of its very few duties in the economy, namely to provide a predictable and non-obstructive legal and regulatory framework. In upsetting that stable framework, a government engaged in fiscal-crisis reaction does yet more harm, long term, to an economy that is already hurt by a rapidly rising government burden.

Inevitable crisis, impossible response

When a country reaches a certain point, a fiscal crisis becomes inevitable. While some questions remain unanswered as to exactly when and how that point is reached, there is little question about what a government’s options are once it passes that point. Experience of varying degrees of fiscal crises in Europe suggests that when a country has maxed out its credit with the global debt market, and when the central bank has tapped out its ability to monetize deficits, all that remains is a series of fiscal measures aimed exclusively at crisis mitigation. There is no longer any room for proactive anti-deficit measures.

Once the crisis becomes inevitable, the response that the government can produce becomes impossible. Rapid spending cuts and tax increases may improve the budget upfront, but their macroeconomic consequences can almost as quickly neutralize whatever gains government made in reducing the deficit.

Adding insult to injury, the unpredictability of spending cuts and the unpalatability of tax hikes can put a significant political price tag on austerity.[15] In April 2010, before the Greek government had started on its first Troika-imposed austerity package, some analysts already pointed to the impossibility of the task they were charged with. Explained Kai Lange of the German business newspaper Manager Magazin:[16]

According to an assessment by Deutsche Bank, Greece is in for a “Herculean challenge”. The country will push its deficits down from its current 13.5 percent of GDP to two percent of GDP. It is expected that the strict austerity measures will slow economic activity by almost ten percent through 2012. Growth is a prerequisite for alleviation of the debt burden – economic activity must not be depressed.

Lange succinctly summarizes the situation that the Greek government had put itself in. At the start of the austerity era, in 2010, the budget deficit was 11.2 percent of current-price GDP. If the government had responded to this deficit with an equally balanced combination of higher taxes and spending cuts, the deficit reduction would have required an 8.8-percent cut in total government spending and an increase in tax revenue by 11.1 percent.

In a U.S. context, these tax increases would increase the tax burden on an average family of two adults and two children by $4,800 per year.[17] This burden would be imposed on them directly in the form of higher income taxes, or indirectly through rising corporate taxes (passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices and to employees in the form of layoffs and pay cuts).

Drastic, rapid-fire spending cuts of the aforementioned magnitude would likely cause a political uproar in American politics. This is also what happened in Greece. As a testimony to the virtual impossibility of the legislative situation created by a fiscal crisis, in a January 2010 closed meeting Troika officials discussed “how to press Athens to forge ahead” with highly unpopular anti-deficit policies.[18] Similar discussions took place within the IMF at the time.[19]

Conceivably, the political turmoil would have been worth the while if the economy would have responded positively to the first, or the first couple of austerity packages. However, that did not happen: the Troika itself admitted that the policies it imposed on Greece were ineffective.[20] By October 2011 they warned of consequences from their own austerity policies that they initially had not accounted for. The Greek economy, they said, was in a substantial decline and would “contract by 15% from 2009 to 2012”.[21]

These insights did not lead the Troika to re-evaluate its fiscal policies. On the contrary, it doubled down and demanded more and faster anti-deficit measures.[22]

Herein lies a very important policy lesson for the United States. Once we cross the line between a fiscally troubled situation and an overt fiscal crisis, and the global debt market expects austerity policies similar to those in Greece, Congress will be locked on a policy path that is destructive both politically and economically.

This outlook should serve as a stark warning that our elected officials better take the opportunity to reverse course on big spending, before it is too late.

__________________________________

* Ph.D., political economist and associate scholar with the Center for Freedom and Prosperity. Dr. Larson has a total of 20 years of experience in politics, political economy and public policy, stretching across three countries. His research is published by referee journals and free-market think tanks, and in books such as The Rise of Big Government: How Egalitarianism Conquered America (Routledge, 2018) and Industrial Poverty (Gower/Routledge 2014).

The Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization operating under Section 501(C)(3). It is privately supported and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

_______________________________________________

Endnotes

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/jan/28/greece-papandreou-eurozone

[2] https://www.wsj.com/articles/daniel-j-mitchell-tax-credits-wont-lift-economic-growth-1408576960?cb=logged0.6939418085385114

* Disaggregated data for state and local government spending is only available for a limited period of time.

[3] Larson, Sven: The Rise of Big Government: How Egalitarianism Conquered America; Routledge, 2018.

[4] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53651-outlook.pdf

[5] For a street-level perspective on these cuts, see: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/07/03/deadly-austerity-greece-health_n_7718306.html accessed 9/24/17

[6] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32000D0427&from=EN

[7] http://www.bbc.com/news/business-13940431

[8] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/18/world/europe/papademos-says-greece-could-force-creditors-to-take-losses.html

[9] http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/schuldenkrise-griechisches-parlament-billigt-sparprogramm-1.1282416

[10] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-20996508 accessed 9/27/17

[11] https://www.cnbc.com/2015/07/20/how-greek-firms-are-coping-with-massive-tax-hikes.html accessed 9/27/17

[12] http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-greece-economy-tax/greeces-vat-tax-hike-is-counterproductive-trade-association-idUKKCN0YF1DN accessed 9/27/17

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/16/tax-hikes-greece-coffee-austerity-economy-bailout accessed 9/27/17

[14] http://www.dw.com/en/higher-tax-burden-for-greeks-in-2017/a-36974136 accessed 9/27/17

[15] https://web.archive.org/web/20111103195312/http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/breaking/2010/0423/

breaking28.html

[16] Author’s translation; original German text: “Nach Einschätzung der Deutschen Bank steht Griechenland vor einer “Herkulesaufgabe”. Hellas will seine Neuverschuldung von derzeit 13,5 Prozent des BIP binnen vier Jahren auf 2 Prozent des BIP drücken. Der strikte Sparkurs dürfte die Wirtschaftsleistung bis 2012 um knapp 10 Prozent einbrechen lassen. Wachstum ist aber Voraussetzung für eine Entschuldung – die Konjunktur darf nicht vollends abgewürgt werden.” http://www.manager-magazin.de/finanzen/artikel/a-690920.html

[17] This number does not take into account the distribution of the federal income-tax burden that places a disproportionate amount of the tax burden on high-income families.

[18] https://www.wsj.com/articles/no-headline-available-1391179002?tesla=y

[19] https://www.wsj.com/articles/past-rifts-over-greece-cloud-talks-on-rescue-1381197278?tesla=y

[20] http://www.protothema.gr/news-in-english/article/153442/eu-give-greece-the-sixth-tranche/

[21] https://www.theguardian.com/business/blog/2011/oct/20/eu-crisis-emergency-talks#block-27

[22] http://www.ekathimerini.com/145123/article/ekathimerini/news/troika-wants-faster-cuts