July 2018, Vol. XII, Issue II

Fiscal Crisis in America, Part 1:

Is A U.S. “Greek” Economic Disaster Possible?

By Sven R. Larson*

The very idea of a Greek-style fiscal crisis in the United States is likely to provoke frowning disbelief. This the world’s largest economy cannot suffer a crisis of such grave proportions; after all, a necessary condition for a crisis would be that the U.S. government runs out of credit. With the global strength of the dollar, the Federal Reserve should be able to continue as the nation’s last-resort lender for a very long time to come.

There is no doubt that the Federal Reserve is highly capable as buyer of government debt, and that it can probably continue in that capacity for some time still. However, the credit worthiness of the U.S. government does not solely depend on the central bank, but on a number of other factors; under some conditions, even a highly respected central bank like the Federal Reserve may lose its ability to shield a deeply indebted welfare state from the verdict of the global debt market.

Eventually, the capability of the Federal Reserve will be determined by two simple, yet central fiscal variables: tax revenue and government spending. If the two diverge far enough, and the pace of the divergence is fast enough, there is a more than theoretical possibility that even the credit line from the Federal Reserve will prove inadequate for the U.S. Treasury.

So far, nobody has been able to pinpoint exactly when this breaking point appears. There is a good reason for this: there is not enough historic experience of fiscally collapsing welfare states with globally established currencies to provide useful historic experience.

What history does provide, however, is the experience with fiscal collapse. One does not have to go as far back as to the Weimar Republic; the most notorious case in our time, Greece during the Great Recession, is informative enough. At a point in time where U.S. interest rates are rising, and forecasts again point to a growing budget deficit even as GDP growth is expected to pick up, it is time to examine the case for a Greek-style fiscal crisis in the United States.

What is a Fiscal Crisis?

The single most important characteristic of a fiscal crisis is that legislators lose control over the budget deficit. Under regular circumstances of fiscal policy, a nation’s legislature can follow its regular time table on passing a budget and changing taxes. Under fiscal panic, external circumstances demand changes to spending and taxation at a far greater pace than is normal and prudent for the legislature.

When, for example, debt-market investors lose faith in a nation’s ability to honor its treasury bond obligations, they demand a rapid increase in the risk premium on those bonds. The risk-premium demands pile on to the cost of existing debt and to new borrowing at such a pace that the legislature feels obligated to take extra-ordinary action against its budget deficit.

The prevailing idea among legislators and economic analysists is that, in a situation of fiscal panic, it is imperative that the legislature reacts quickly to rising interest rates. The sooner it reacts, the better. At the same time, when the legislature is under pressure to take immediate anti-deficit action, a rapid response will inevitably be focused on tax hikes and spending cuts that will have immediate, upfront effects on the deficit.

Due to the swiftness with which rapid-response measures are crafted and passed, the long-term effects are rarely given appropriate attention. Therefore, as exemplified by the recent fiscal crises in Greece and Spain or in Sweden in the 1990s and Denmark in the 1980s, the long-term effects of fiscal-crisis measures are rarely given appropriate attention. For example, while spending cuts are necessary in any situation with a structural budget deficit, cuts executed under fiscal-panic conditions tend to reduce government without removing obstacles to private sector expansion. A classic example from European cases of fiscal panic are cuts to government-provided health care: while, e.g., government reduces hospital staffing and cuts subsidies of prescription drugs, those cuts do not come with regulatory removals or tax cuts to allow the private sector to fill the gap created by the spending cuts.

In Europe, the debate over fiscal-crisis policies has often characterized the spending cuts as an attack on the welfare state by forces wanting to return the economy to small government and the free reign of capitalism. However, this is not the case: not only do spending cuts under fiscal panic maintain government spending programs – only at smaller dimensions – but they also come with unchanged or higher taxes. The net result, therefore, is an expanded government: taxpayers pay the same or higher price for watered down services and benefits.

The macroeconomic outcome of anti-deficit measures in a fiscal crisis are negative. By increasing the net price of the welfare state, government actually makes it costlier for businesses and families to live and work. Over time, this reduces economic growth, exacerbating the problems for government to fund its spending. In Greece, depression of growth extended the fiscal crisis that rapid-reaction spending cuts and tax increases were supposed to end.[1]

Trump’s Tax Reform: One for the Welfare State

A necessary condition for a fiscal crisis is that government is running a chronic budget deficit. The United States meets this condition in abundance: the federal budget has been in the red 90 percent of the time over the past half century. However, far more aggravating is the fact that fiscal policy under the Trump administration is showing signs of compounding the chronic-deficit problem:

- On the revenue side, the Trump tax reform broke with a long-standing tradition in American tax policy, trying to pair upfront tax revenue collection with incentives toward economic growth;

- On the spending side, Congress has removed restrictions on spending, and there is growing support for major new entitlement programs.

While these signs of a possible looming fiscal crisis are not without challenge, they present a picture of our near-term future that merits closer examination.

A central tenet in supply side economics as applied to tax reform is that it prioritizes economic growth over the collection of tax revenue. As carefully explained by Arthur B Laffer, a boost in tax revenue is a bonus, so to speak, but it is achieved entirely through a surge in private sector economic activity.[2] Unfortunately, with the Trump tax cuts, U.S. tax policy appears to have taken a turn away from growth-oriented supply side theory.

The break with tradition is significant, especially in view of the three supply-side oriented, major tax reforms that Congress has passed since World War II. The first took place under President Kennedy, whose tax cuts ended a decades-long era with 90+ percent marginal income taxes. In 1964, the Kennedy cuts reduced the top tax rate from 91 to 77 percent and the bottom rate from 20 to 16. A year later they declined to 70 and 14 percent, respectively.

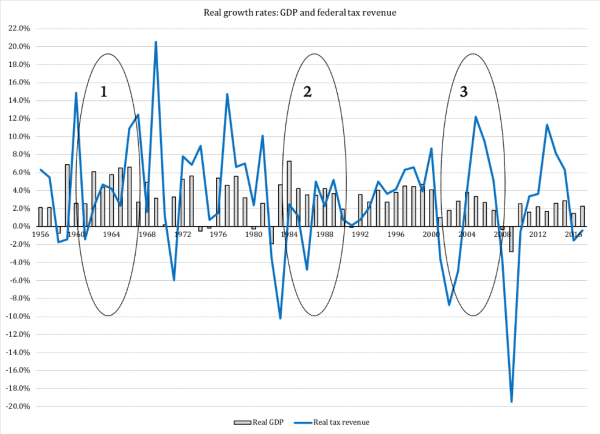

While the number of tax brackets remained largely the same after the reform as before, as Figure 1 explains the effect on economic growth and tax revenue are clearly visible in economic statistics (period 1).

The Reagan-era tax cuts had an even stronger supply-side profile. After the initial reduction of the top personal-tax rate from 70 to 50 percent in 1982, the big change took effect five years later when the number of brackets fell from 15 to 5 and the top rate came down to 38.5 percent.

A year later, only two brackets remained: 15 and 28 percent.

As shown in the second episode in Figure 2, the Reagan tax cuts were followed by a sustained period of GDP growth and growth in federal tax revenue:

Figure 1

Raw data sources: Office of Management and Budget; Bureau of Economic Analysis

Presidents Bush Sr. and Clinton gradually increased the number of brackets to five, raising the top rate to 31, then to 39.6 percent. President Bush Jr. added a sixth bracket but brought the top rate down to 35 percent. Since his reform was milder in its supply-side profile than the Reagan reform, it is understandable the the third period in Figure 1 exhibits a smaller bump in growth and a more temporary increase in tax revenue.

When a tax reform combines a reduction in tax rates with a reduction in tax brackets, the effect is a weakening of the punitive marginal-rate profile of the income tax. This can be accomplished even without a reduction in the number of brackets, if the reform noticeably reduces tax rates. In this regard, the Trump tax reform has broken with tradition. Contrary to both supply side theory in general and the Laffer lessons in particular, President Trump maintained the Obama-era seven brackets, as well as its top rate. While reducing the tax burden for lower income earners through more generous deductions, the bulk of the reform took place on the corporate side of the tax code.

By focusing its tax-burden reduction on lower income earners, the reform has exacerbated an already-existing bias in the distribution of the tax burden. Fewer people are responsible for even more of the tax revenue.

At the same time, once a taxpayer pays more in taxes than he gets in deductions and credits, the effective tax rate he encounters rises just as fast as it did before the reform.

There is a policy strategy behind this profile of the reform, namely to preserve as much revenue as possible while still hoping to generate a sustained boost in GDP growth. There is little doubt that the significant cuts in corporate income taxes have already generated more growth, but since its effect on household income and purchasing power is only indirect – increasing employment and helping businesses increase pay – the personal side of the tax code still offers a very steep marginal-tax ladder. It is therefore a valid question how much of that generated new income will translate into sustained increases in household spending and savings.

From a tax revenue side, this leads to questions about the future of the federal government’s tax revenue, and consequently its deficits and its debt.

This is no small problem. When fewer people pay a larger share of all taxes, there is a greater risk for volatility and unpredictability in tax revenue. Already before the Trump tax reform, the distribution of the personal tax burden was heavily concentrated to the upper layers of income earners. Already before the Trump tax reform, the personal-income tax burden was heavily concentrated: one quarter of all taxpayers, in other words those who make more than $100,000 per year, paid 80 percent of all personal federal income taxes.[3] Since personal federal income taxes, and the social security taxes that come on top of them, account for 80 percent of all federal tax revenue, this group pays about 64 percent of all federal taxes.[4]

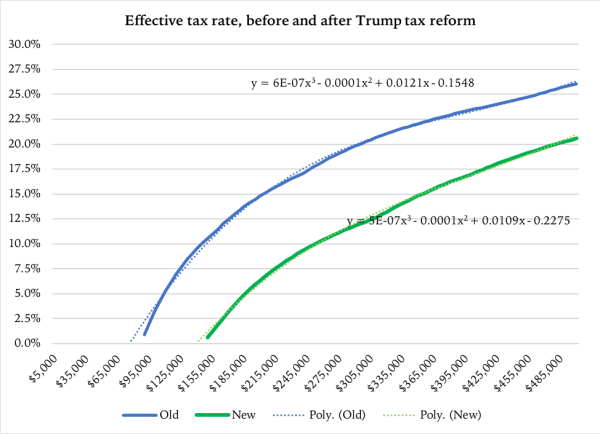

Even fewer are going to be responsible for even more taxes. Figure 2 explains how the progressive profile of the personal income taxes, for a married couple filing jointly, has not changed with the Trump reform. The effective tax rate on a person’s income rises as fast as it did before:[5]

Figure 2

Source for raw data: Internal Revenue Service

While low-income families get to keep more of their money – obviously good for both them and the economy – the taxation hill is just as steep as it was before (as illustrated by the trend line equations in Figure 2). However, with the expanded standard deduction, up from $13,000 to $24,000 for a married couple filing jointly, the reform has exacerbated the concentration of the tax burden.

Why did Congress prefer to keep the steep marginal profile? There was no real debate about this prior to the reform, but it is not far-fetched to conclude that Congress and President Trump were concerned about losing tax revenue upfront. Growth-oriented, Laffer-inspired tax reforms sacrifice upfront revenue because the first priority is to give the private sector more room to grow. A boost in revenue comes only when the economy responds to the growth incentives that are put in place by lower tax rates.

A growth-minded Congress would accept the initial loss of revenue for the good of a growing economy. However, by maintaining high marginal tax rates, they signal a preference for upfront tax revenue over growth stimulus.

The economy ends up paying a price for this focus on tax revenue. Progressive income taxes discourage productive workforce participation. When the price for earning the last dollar increases beyond a certain point, people choose not to increase their earnings. More effort is instead diverted to reducing the tax burden, a point that even liberal economists like Austan Goolsbee will concede.[6]

A Decades-Old Spending Problem

When a tax reform is biased toward upfront tax revenue more than economic growth, it conveys a political message that there are no major reductions in government spending to be expected. This has negative effects on government finances, both short term and long term. The short term effect is that entitlements aimed at lower income households will remain in place, and with them their work-discouraging incentives. Spending programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, SNAP (a.k.a., food stamps) and Medicaid create a high, effective marginal tax on lower incomes: a family earnings less than $40,000 can lose so much in entitlements, while encountering higher income taxes, that their effective marginal tax rate can match that of a household making ten times as. much (Larson 2018).

Long term, the work-discouraging combination of steep marginal income taxes and redistributive entitlements slow down economic growth. They also drain the federal budget, where, absent reform, spending continues to outgrow tax revenue.

There is further evidence that the Republican-led Congress does not have major spending reform in mind. For example, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has been protective of Obamacare funding since the birth of the reform.[7] He worked closely with Senator Schumer (D-NY) on the February 2018 bipartisan budget deal,[8] which suspended the debt ceiling to March 2019, ended budget sequestration and killed the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) in Medicare.

Technically, the IPAB never had any influence over Medicare spending, but its elimination signals a policy priority that is not conducive toward spending restraint. It fits in the context of the suspension of the debt ceiling and the termination of the sequester mechanism, without any other structural spending measures replacing them.

A tax reform that statically focuses on preserving tax revenue, as opposed to dynamically pursuing more revenue, goes hand in glove with a spending policy that removes spending restraints. However, these policy priorities are mere symptoms of a more deeply rooted, structural problem in the federal government’s budget. The threat of a Greek-style fiscal crisis is rooted at this level and is known as the welfare state.

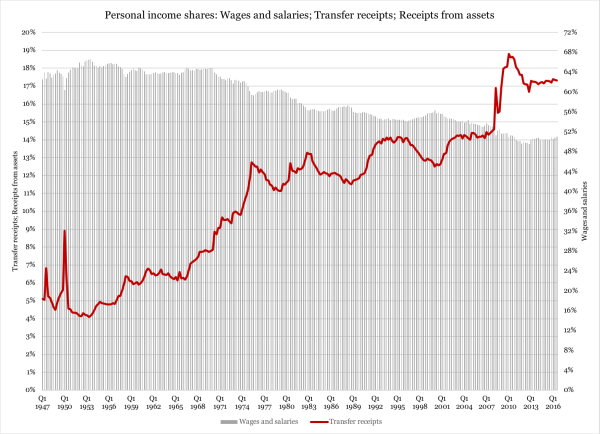

Since the War on Poverty began, tax-paid entitlements have transformed the average American household budget. Handouts from government have increased their share of personal income from less than seven percent in 1964 to more than 17 percent half a century later. At the same time, work-based income from wages and salaries has declined to where it currently barely accounts for 50 percent of U.S. personal income:

Figure 3

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Our dependency on government has gone so far that American families now depend more on transfers from government than on investment income. In 2016,

- Earnings from dividend and interest accounted for 14.9 percent of all the personal income in the country; at the same time,

- Transfers, a.k.a., entitlements, provided 17.4 percent of our total personal income.

Investment-based income is not just for the rich. A middle-class family that has saved for their retirement over the years and draws from their retirement account when they leave the workforce, live off private investments. A family that sells a house to buy a smaller one, and gradually spends down the “left over” money, is also living off investment income.

In other words, it is not at all strange to middle-class America to reap the fruits of prudent, long-term savings. Yet the rise of welfare-state entitlements has come with a decline in long-term financial self-reliance: tax-paid entitlements have been more important to personal finances than investment income since 2009.

Growing dependency on government handouts raises the political price tag for spending reform. While this can explain why Congress and the Trump administration prioritize tax revenue over restraint on outlays, it does not explain how they intend to bring an end to U.S. budget deficits, let alone prevent a possible fiscal crisis.

New entitlements: paid family leave

Paid family leave is an income-security entitlement for people who are active in the workforce and who are of child-bearing age. The idea is that a parent with a newborn child gets a number of weeks off from work while being paid by government. This is a popular program in Europe and has a following in Canada as well.

There is now growing support for it here in the United States, support that has reached deep into the layers of the Republican party. President Trump included a primitive version of paid leave in his first budget; in Congress, Senator Macro Rubio (R-FL) has emerged as the leading Republican proponent. He dipped his toes into this issue already in 2015, when he gave a speech to the Values Voter Summit explaining[9]

his plan to provide a 25 percent tax credit to any business that offers four to 12 weeks of paid leave. Mr. Rubio gave an example of a business that gives an employee $400 per week for four weeks of leave, saying the business would earn a $400 tax credit.

A tax credit program looks innocent enough, so innocent that Senator Fischer (R-Neb.) decided to tag it on to the Trump tax reform.[10] In fact, “tax credit” sounds like there is no government spending involved, because all it does – right? – is to let people keep more of their money.

Technically, this is correct, and it is always better when government has less tax revenue than more. However, to make sense for low-income families, Senator Rubio’s tax credit would have to be refundable. If not, the cut would only matter to the decreasing number of working Americans who are net payers of federal income taxes.

Senator Rubio has not explicitly promoted his paid-leave program as refundable, but there is no way either Republicans or Democrats would accept a new tax-credit program that is not refundable. Otherwise, it would be limited to high-income earners only.

Recently, Senator Rubio has modified his stance on paid leave, but not in the fiscally conservative direction. Together with Senators Ernst (R-IA) and Lee (R-UT) he has proposed a spending model where paid leave is tagged on to Social Security.[11] As Bloomberg News explains, this program, originally introduced by the Independent Women’s Forum (IWF), would

let employees set aside some of their Social Security contributions to allow them to be paid while out on parental leave. … The measure would allow a worker to deduct Social Security contributions to use for pay when on leave from work for situations including the birth of a child. To repay those funds, the worker would delay retirement, those on the call said.

This Social Security-based paid leave program could easily become a major budget boondoggle. The Social Security system is already close to insolvency: according to the Social Security Administration’s own estimates, the program goes insolvent in 2034.[12] If Social Security were amended with a paid leave program as the IWF suggests, young mothers and fathers could draw billions of dollars in benefits from the program between now and Insolvency Day.

Suppose half of the parents of newborns, or two million people, use this program. Suppose they, on average, take a modest $1,250 in benefits per month for six months. That amounts to $15 billion per year.

If this program started in 2019, by 2034 it will have drained Social Security for 16 years, depleting the Trust Fund of almost a quarter of a trillion dollars.

The mere prospect of a sped-up path to Social Security insolvency is serious enough to raise red fiscal-crisis flags above Capitol Hill. However, support for this idea is widespread among right-of-center organizations. In 2015, American Action Forum (AAF) published a report favoring a federal paid-leave program.[13] In 2016 they ramped it up, proposing a full-blown paid-leave program that should make every liberal green with envy.[14]

The American Enterprise Institute favors paid family leave.,[15] as does the pragmatically libertarian Niskanen Center.[16]

None of these organizations have provided credible calculations as to the cost of paid family leave. This is troubling: under realistic conditions, the annual cost of a standard paid-leave program could run as high as as high as $391 billion, though under some conditions the yearly cost could surge past half-a-trillion dollars.[17]

New entitlements: single-payer health care

In addition to the prospect of paid family leave, and the addition of possibly hundreds of billions of dollars in annual federal spending, there is growing support in right-of-center circles for single payer health care. The failure of the Republican-led Congress to repeal Obamacare – only removing the individual mandate – has reignited the debate over what would be the largest entitlement ever created in the history of the United States.

While support for this all-out government health care system has not yet surfaced among Congressional Republicans, many of their ideological peers around the public-policy arena are sounding off in its favor. For example, on March 26, 2017, center-right opinion commentator Jennifer Rubin explained in the Washington Post that anyone who was opposed to Obamacare and more government in health care was resorting to “anti-government hysterics”.[18] One of the policy recommendations she dispensed to Republicans in Congress was to keep Obamacare and expand Medicaid.

Two days later New York Times opinion columnist David Leonhardt concurred, calling on Republicans to expand government-paid health care “in a conservative-friendly way”.[19] He also predicted that Republicans will come down in favor of single-payer health care.

On March 30, 2017, in the New York Post, conservative-leaning commentator and Scalia Law School professor Francis H Buckley urged Republicans to abandon their “do-nothing strategy” on health reform.[20] Instead, he said, they should go for a Canadian-style single payer system.

The same day, the late conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer noted:[21]

A broad national consensus is developing that health care is indeed a right. This is historically new. And it carries immense implications for the future. It suggests that we may be heading inexorably to a government-run, single-payer system. It’s what Barack Obama once admitted he would have preferred but didn’t think the country was ready for. It may be ready now.

Krauthammer also cautioned his readers to not be surprised “if, in the end, single-payer wins out”. His prediction was echoed a week later by Jesse Walker at the Reason Foundation’s Hit & Run Blog[22] and again on May 8, 2017, when Washington Post opinion writer Eugene Robinson explained that Republican efforts to repeal Obamacare “are paving the way” for single-payer health care.[23]

Another, similar prediction came in October 2017 from Tevi Troy, CEO of the American Health Policy Institute. Writing for Commentary Magazine,[24] Troy explained that single-payer health care would rise from the ashes of a Republican surrender before Obamacare:

If the Republicans could not repeal Obamacare at a time when they hold the House, the Senate and the White House, and when nearly all of these GOP officials were elected in no small measure on the basis of their personal commitments to repeal and replace Obamacare, when might they ever repeal it – or any large-scale government program?

Troy points out that the law’s combination of an individual mandate and subsidies for insurance premiums effectively constitutes universal coverage. While the insurance mandate was repealed in 2018, the rest of Obamacare remains in place. As a result, those who drop insurance without the mandate, yet who still cannot afford to buy a plan because of the cost-driving features of Obamacare, are going to flock to Medicaid.

Since the Republicans in Congress are not willing to return America to a market-based health insurance system, they are left with two options: expand Medicaid for all states or go for a “Medicare for all” solution.

Either way, the GOP has de facto made Obamacare irrepealable. There is a case to be made that Congress is mission-creeping into single payer health care.

Has America Crossed the Rubicon?

The combination of a tax reform that is not unequivocally supply-side in nature and a trajectory in government spending that points decisively upward, is a compelling case for a U.S. fiscal crisis in the near future. Is it strong enough to make a Greek-style crisis inevitable?

The answer to this question depends on how strongly the American political establishment stands behind the fiscal institutions – entitlement programs and progressive taxes – that constitute the case for a crisis. Growing right-of-center support for even more entitlement programs is worrisome; as political scientist Patrick Deneen explained in the Fall 2017 issue of the Hedgehog Review, the American political landscape could very well be locked in on the same trajectories exhibited in federal government finances.

Deneen defines the political landscape not as a struggle between opposing ideologies, but a battle “between liberalism’s two sides”. The political discourse no longer includes a dichotomy between “protection of individual liberty and expansion of the state’s efforts to redress injustices”. The state and the individual are seen as two mutually dependent vessels; the prevailing opinion is that they are inextricably tied together.

If one replaces Deneen’s liberalism with egalitarianism, the picture gets its proper context: the egalitarian welfare state appears to have been overwhelmingly successful, thus forcing a consensus between radical proponents and ardent opponents. Put plainly: Democrats built the welfare state and Republicans have polished it. Over time, a consensus has emerged around big government, a consensus where the only debate is over how to continue to expand the role of government in people’s lives.

If this interpretation of the American landscape is correct, there is little to hope for from the two big political parties in terms of awareness of a looming fiscal crisis. In fact, ignorance of the possibility of a crisis in itself increases the likelihood of a crisis. The stronger the consensus around

__________________________________

* Ph.D., political economist and associate scholar with the Center for Freedom and Prosperity. Dr. Larson has a total of 20 years of experience in politics, political economy and public policy, stretching across three countries. His research is published by referee journals and free-market think tanks, and in books such as The Rise of Big Government: How Egalitarianism Conquered America (Routledge, 2018) and Industrial Poverty (Gower/Routledge 2014).

The Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization operating under Section 501(C)(3). It is privately supported and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

_______________________________________________

Endnotes

[1] Part 2 in this series of papers will explain in detail how the Greek crisis unfolded.

[2] Laffer (2004).

[3] See IRS personal income and tax data: https://www.irs.gov/statistics

[4] See Office of Management and Budget: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/

[5] The effective tax rate is the ratio between the actual amount we pay in taxes and the actual taxable income.

[6] See Goolsbee (1999).

[7] http://www.conservativehq.com/node/14284

[8] https://townhall.com/columnists/donaldlambro/2018/02/09/mcconnells-unholy-big-budget-alliance-with-schumer-and-the-democrats-n2446327

[9] https://www.nytimes.com/politics/first-draft/2015/09/25/marco-rubio-proposes-tax-credit-to-spur-paid-family-leave/

[10] https://www.fischer.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2017/12/fischer-paid-family-leave-proposal-included-in-tax-reform-conference-report

[11] https://www.bna.com/senate-republicans-readying-n57982088437/

[12] https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/fast_facts/2017/fast_facts17.html#page35

[13] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/menu-of-women-and-family-friendly-work-options/

[14] https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/08/a-new-conservative-entitlement-for-paid-family-leave/495686/

[15] https://www.aei.org/feature/paid-family-leave/

[16] https://niskanencenter.org/blog/family-allowances-conservative-alternative-paid-family-leave/

[17] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3015990

[18] https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/right-turn/wp/2017/03/26/republicans-dangerous-health-care-delusions/?utm_term=.433ba2ecf035

[19] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/28/opinion/republicans-for-single-payer-health-care.html

[20] https://nypost.com/2017/03/30/why-trump-should-embrace-single-payer-health-care/

[21] https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-road-to-single-payer-health-care/2017/03/30/bb7421d0-156c-11e7-ada0-1489b735b3a3_story.html?utm_term=.87a8069d0654

[22] https://reason.com/blog/2017/04/06/republicans-for-single-payer

[23] https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/republicans-are-accidentally-paving-the-way-for-single-payer-health-care/2017/05/08/3fc40ab2-3422-11e7-b4ee-434b6d506b37_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.444dcaf074b7

[24] https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/republicans-might-bring-single-payer-health-care/

References:

Goolsbee, Austan: Evidence on the High-Income Laffer Curve from Six Decades of Tax Reform; Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, September 1999.

Laffer, Arthur: The Laffer Curve: Past, Present and Future; Backgrounder No. 1765, The Heritage Foundation, June 2004.

Larson, Sven: The Rise of Big Government: How Egalitarianism Conquered America; Routledge, 2018.

Troy, Tevi: How Republicans Might Bring About Single-Payer Health Care; Commentary Magazine, Sept. 2017.

———

Image credit: Bjoertvedt | CC BY-SA 3.