The United States and other western nations became rich during the 1800s thanks to a combination of rule of law and very small government.

Sadly, very few nations – most notably East Asian tiger economies – have become rich in the modern era. Yes, some other countries have grown, but they are not on a path to converge with rich nations.

Chile, however, may be an exception to that unfortunate pattern. It has enjoyed amazing levels of growth since a shift to free-market policies starting about 40 years ago. It is now the richest country in Latin America and if its “improbable success” continues, it will soon be comfortably part of what used to be called the first world.

Chile, however, may be an exception to that unfortunate pattern. It has enjoyed amazing levels of growth since a shift to free-market policies starting about 40 years ago. It is now the richest country in Latin America and if its “improbable success” continues, it will soon be comfortably part of what used to be called the first world.

The flagship reform in Chile was the creation of a funded retirement system based on personal accounts. Basically universal IRAs.

Writing for the Weekly Standard, Fred Barnes shared what he learned about the nation’s private retirement system.

The rags-to-riches Chile story lives on as a model of what a poor country can achieve if it spurns socialism and adopts free markets and democracy. Peru is now copying Chile. More may follow. …Chile was once a Third World country headed downhill economically after Salvador Allende was elected president in 1970…bent on creating a Marxist state.

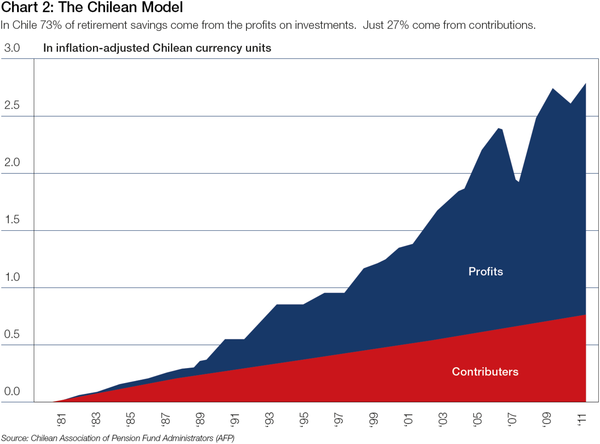

In 1973, the military led by General Augusto Pinochet staged a coup. …When he took over, Chile had one of the highest rates of poverty in South America. It was a basket case. Now it has the continent’s strongest economy. Without Pinochet’s having heeded the advice of economist Milton Friedman, imposed capitalism, and hired a team of free market economists, many trained at the University of Chicago, the rise to First World status wouldn’t have happened. One of the economists was José Piñera, brother of the new president and Harvard-educated. He created a stable, fully-funded pension program that has become a monument to the success of private markets. …Piñera released a study in January that found “72 percent of the capital accumulated in the personal retirement account of the average Chilean worker, after 36 years in the private pension system, comes from the return on the investments done with their contributions.” That’s a long way of saying the plan is a dazzling success.

Though there are opponents, mostly those inspired by the communist regime in Cuba and a Pope who thinks we should worship the state.

But obstacles remain. …Even with Fidel Castro gone, Cuba exports communism as aggressively as it once did sugar. …socialists have an ally in Pope Francis, who spent three days in Chile in mid-January. …there’s a disconnect between how people here feel about capitalism—as a concept anyway—and the economic success they are experiencing. Pinochet is partly to blame, I suspect. He’s a hard man to credit, given his bloody takeover.

Barnes’ final point is also important.

I’ve had many people tell me that personal accounts are bad because they were implemented during Pinochet’s reign. But that’s a silly argument, sort of like deciding to be against free trade because the dictatorial Chinese government opened up to the global economy.

As far as I’m concerned, tyrannical leaders are awful and should be condemned, but if they happen to grant citizens a slice of economic liberty, that’s a silver lining to an otherwise dark cloud.

Back to our main topic, Monica Showalter, in a column for the American Thinker, explained what makes Chile’s system a role model for the United States.

…the Chilean Model…shows some spectacular new results for ordinary citizens… the Chilean Model is working, big time. Basically, you skip Social Security taxes for starters, which leaves you a lot more money to play around with.

You then put 10% of your income into a government-certified private pension account (and you have many choices among them)… This is mass-scale wealth creation, and it benefits workers most of all. …Chile has no pension crisis as most of the rest of the developed world does – no worries about a “trust fund” and no Social Security “cuts” to speak of. This is why. Thirty nations have adopted the same plan… the left hates this stuff. It keeps workers out of the clutches of unions and un-dependent on government handouts. Of course leftists want it gone. They tried hard in Chile to turn workers against this pension idea.

And here’s a chart from her article showing how investment returns have played a big role in helping ordinary Chileans build nest eggs for their old age.

Let’s look at some additional research.

In a monograph published by the U.K.-based Institute of Economic Affairs, Kristian Niemietz takes an in-depth look at Chiles’s approach.

Taken together, the value of the assets accumulated by Chilean pension funds is equivalent to about two thirds of the country’s GDP (Figure 1). This places Chile in the same league as countries which have had private pensions for over a century, and miles ahead of countries with traditional Bismarckian systems…

The poverty rate among the elderly is lower than that of the population as a whole – 3.9 per cent vs. 10.3 per cent, or 8.4 per cent vs. 14.4 per cent, depending on the poverty measure used… Chile’s 1981 pension reform has given rise to a number of positive economic spillover effects: the prefunded system has been an active ingredient in the accelerated economic development that the country has been experiencing since the mid-1980s. …It has increased employment, especially in the formal sector… It has boosted the development and sophistication of Chile’s capital markets, and thus raised Total Factor Productivity… Despite the current backlash against it, Chile’s pension system is a success story. The system has achieved consistently high rates of return. It offers excellent value for money and solid pensions for those who contribute regularly. … The official retirement age is not as important in Chile as it is in countries with state-run systems. By and large, in that system, people retire when they have accumulated enough savings, not when politicians think they should retire.

Here’s the chart Kristian mentioned in the text. By this important metric, Chile is firmly ensconced in the upper tier of developed countries.

Now let’s address some of the critics.

Under the previous leftist government, there were protests against the country’s famous private social security system and attempts to undermine the model. Indeed, I wrote about that battle back in 2014. And I also noted that even some academics agreed that it would be foolish to undermine a successful approach.

Let’s see what’s happened since then. The Economist reported about the complaints about a year ago.

…tens of thousands of Chileans in Santiago…protest against the country’s privatised pension system. Organisers—a mix of unions, pensioners’ associations and consumer-advocacy groups—say that… Pensions are too small…benefits have not measured up to people’s unrealistic expectations.

The scheme’s founders told workers that if they contributed continuously throughout their careers they would receive a generous 70% of their final salaries upon retirement. …But most workers contributed far less. Women took time off to raise children (and retire earlier than men). Many Chileans spent time in informal jobs or unemployed. On average, they contribute for only 40% of their prime working years. …The system has generated high returns for pensioners, averaging 8.6% a year between 1981 and 2013. But…high fees have bitten a huge chunk out of those returns, reducing them to 3-5.4%.

Though the article also noted all the benefits of personal accounts.

Rather than saddle the government with an unaffordable pay-as-you-go system, in which today’s taxpayers support today’s pensioners even as the population ages, Chile created one in which workers save for their own retirement by paying 10% of their earnings into individual accounts. These are managed by private administrators (AFPs). …the system worked. Contributions to the AFPs flowed into capital markets, which boosted growth. Annual GDP growth from 1981 to 2001 was 0.5 percentage points higher than it would have been without the investment, according to one study. This helped lift millions of people out of poverty.

The last couple of sentences of the above passage are worth highlighting. As I’ve noted, even small differences in economic growth – if they are sustained for a long period – make a huge difference in terms of national prosperity. And 0.5 percent more growth every year is actually a big boost when looking at the impact of just one policy.

Last but not least, here’s Ian Vasquez’s response to the attacks on the Chilean system.

Critics in Chile assert that the average pension provided by the private pension fund companies is around $340 per month, which is not better than the public pension system. But as the Chile-based Liberty and Development institute (LyD) has shown, that is like comparing apples to oranges. To calculate the private system’s figures, all those affiliated with it are taken into account, even if they have only contributed to their accounts once in their lifetime.

The corresponding figure for the public pension system, however, only takes into account the pensions of those who have contributed for a minimum of 10 to 15 years, something that leaves out half of the people affiliated with that system. In addition, pensions under the private system are obtained through contributions that amount to 10 percent of wages, while in the public system the contribution is 20 percent. Correcting for those distortions shows that the value of the pensions the AFPs provide is three times higher than that of the public system. …it’s true that many Chileans do not contribute regularly to their retirement accounts because too many work outside the formal sector and getting work is still too precarious for many, that is a problem that affects any pension system, whether public or private, and can only be solved with labor reforms. …Chile’s private pension system can certainly be improved, but the reality is that it has been extremely successful. …old-age pensions no longer represent a burden on the treasury. Pension savings have reached $168 billion, about 70 percent of GDP, which has stimulated high growth and domestic investment, and has put Chile on the verge of becoming a developed country—a remarkable achievement.

Amen. Chile’s system isn’t perfect, but it’s far better, by several orders of magnitude, than the debt-ridden, pay-as-you-go models that are wreaking havoc with the public finances of other countries.

And Chile is prospering in a way unimaginable in other Latin nations.

It would be very nice to have a similar system of personal retirement accounts in the United States. And here’s the cartoon version of the argument.

P.S. Chile also has nationwide school choice.

P.P.S. Bill Clinton supported good Social Security reform and was prepared to work with congressional Republicans (and some Democrats) on good legislation for personal accounts, but that effort was sidetracked by the partisan impeachment fight. A genuine tragedy.

P.P.P.S. I’ve written before about overseas bathroom adventures and I now have another episode to add to the mix from my recent trip to India. I like modern facilities, including ones that have energy-saving features. But building engineers should realize that motion-activated lights may not make sense in bathrooms. At least not when people may be locked in stalls with no good options when the lights go out. Enough said.