Last September, I wrote about some very disturbing 10-year projections that showed a rising burden of government spending.

Those numbers were rather depressing, but a recently released long-term forecast from the Congressional Budget Office make the 10-year numbers look benign by comparison.

The new report is overly focused on the symptom of deficits and debt rather than the underlying disease of excessive government. But if you dig into the details, you can find the numbers that really matter. Here’s some of what CBO reported about government spending in its forecast.

The long-term outlook for the federal budget has worsened dramatically over the past several years, in the wake of the 2007–2009 recession and slow recovery. …If current law remained generally unchanged…, federal spending rises from 20.5 percent of GDP this year to 25.3 percent of GDP by 2040.

And why is the burden of spending going up?

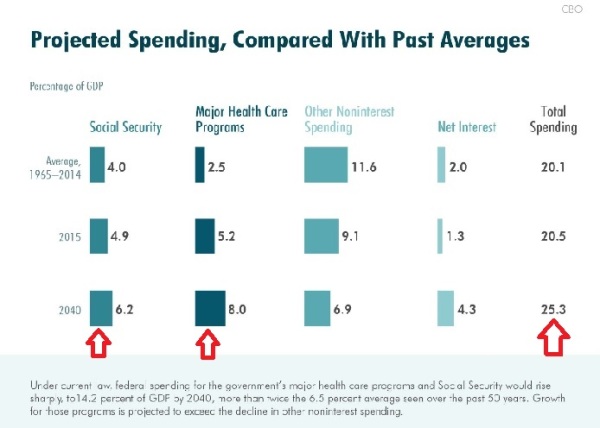

Well, here’s a chart from CBO’s slideshow presentation. I’ve added some red arrows to draw attention to the most worrisome numbers.

As you can see, entitlement programs are the big problem, especially Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and Obamacare.

Even CBO agrees.

…spending for Social Security and the government’s major health care programs—Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and subsidies for health insurance purchased through the exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act—would rise sharply, to 14.2 percent of GDP by 2040, if current law remained generally unchanged. That percentage would be more than twice the 6.5 percent average seen over the past 50 years.

By the way, while it’s bad news that the overall burden of federal spending is expected to rise to more than 25 percent of GDP by 2040, I worry that the real number will be worse.

After all, the forecast assumes that other spending will drop by 2.2 percent of GDP between 2015 and 2040. Yet is it really realistic to think that politicians won’t increase – much less hold steady – the amount that’s being spent on non-health welfare programs and discretionary programs?

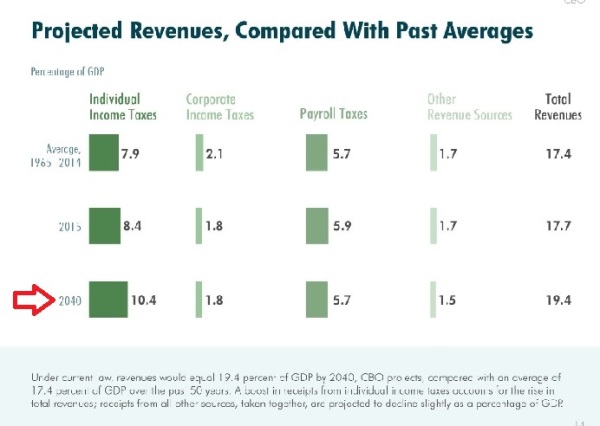

Another key takeaway from the report is that it is preposterous to argue (like Obama’s former economic adviser) that our long-run fiscal problems are caused by inadequate tax revenue.

Indeed, tax revenues are projected to rise significantly over the next 25 years.

Federal revenues would also increase relative to GDP under current law… Revenues would equal 19.4 percent of GDP by 2040, CBO projects, which would be higher than the 50-year average of 17.4 percent.

Here’s another slide from the CBO. I’ve added a red arrow to show that the increase in taxation is due to a climbing income tax burden.

These CBO numbers are grim, but they could be considered the “rosy scenario.”

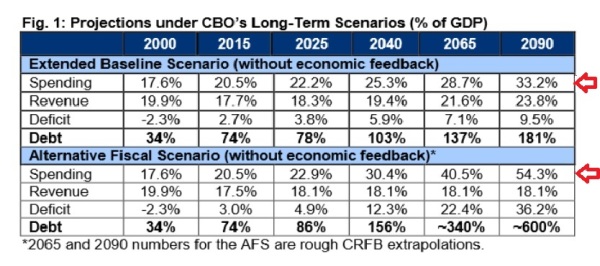

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) produced their own analysis of the long-run fiscal outlook.

Like the CBO, CRFB is too fixated on deficits and debt, but their report does have some additional projections of government spending.

Here’s the key table from the CRFB report. Not only do they show the CBO numbers for 2065 and 2090 under the baseline scenario, they also pull out CBO’s “alternative fiscal scenario” projections, which are based on more pessimistic (some would say more realistic) assumptions.

As you can see from my red arrows, federal spending will consume one-third of our economy’s output based on the “extended baseline scenario” as we get close to the end of the century. So if you add state and local spending to the mix, the overall burden of spending will be higher than it is in Greece today.

But if you really want to get depressed, look at the “alternative fiscal scenario.” The burden of federal spending soars to more than 50 percent of output. So when you add state and local government spending, the overall burden would be higher than what currently exists in any of Europe’s welfare states.

In other words, America is destined to become Greece.

Unless, of course, politicians can be convinced to follow my Golden Rule and exercise some much-needed spending restraint.

This would require genuine entitlement reform and discipline in other parts of the budget, steps that would not be popular from the perspective of Washington insiders.

Which is why we need some sort of external tool that mandates spending restraint, such as an American version of Switzerland’s Debt Brake (which you can learn more about by watching a presentation from a representative of the Swiss Embassy).

Heck, even the IMF agrees that spending caps are the only feasible solution.