I’ve written about the success of Hong Kong (particularly when compared to nations such as Cuba, France, and China), but haven’t paid as much attention to Singapore.

But it’s time to correct that oversight. I’m motivated to write about Singapore because of a story that reveals one of the unique features of that jurisdiction: The bureaucracy gets monetarily rewarded if the economy prospers.

Here are some passages from a Bloomberg report.

In Singapore, civil-servant bonuses rise and fall with the economy’s performance… The nation…links civil servants’ bonuses to how well the $298 billion economy does. …Civil servants are typically paid a variable incentive twice a year, on top of a fixed one-month bonus. The mid-year payment was skipped in 2009, when the economy contracted during the global recession. …“Singapore may be one of the few countries that explicitly pegs bonuses to growth,” said Vishnu Varathan, an economist in Singapore at Mizuho Bank Ltd.

Wow. Think of what that might mean if applied in the United States. Would we get as many crazy growth-sapping regulations from bureaucracies such as the EPA, IRS, and EEOC if the paper pushers knew they would lose bonuses?

To be honest, I’m not actually sure that this system makes much difference in Singapore or, if it does work there, whether it would work the same way in the United States (where bureaucrats seem to get bonuses based on bad behavior!).

But one thing we can say with certainty is that Singapore is an economic success story.

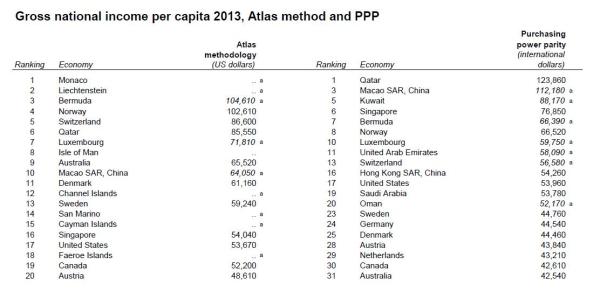

Look at the rankings for per-capita gross national income from the World Bank. You’ll notice a few trends, such as it’s good to be a tax haven (Monaco, Liechtenstein, Bermuda, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Isle of Man, etc) or to have a lot of oil (Qatar, Kuwait, Norway, UAE, etc).

But you’ll also notice that Singapore is one of the world’s most prosperous jurisdictions, regardless of which methodology is used.

So why is Singapore so rich?

Well, there aren’t many natural resources other than ocean access, so the only reasonable explanation is that the country has good economic policy.

And if you look at the latest data from Economic Freedom of the World, you’ll see that Singapore ranks second for economic liberty.

I’m particularly impressed by the nation’s fiscal policy. The corporate tax rate isjust 17 percent and the top tax rate for households is only 20 percent. In other words, there’s no Obama-Hollande class warfare against successful taxpayers.

Equally important, the burden of government spending is very small by world standards, averaging less than 20 percent of economic output since 1990 according to the IMF.

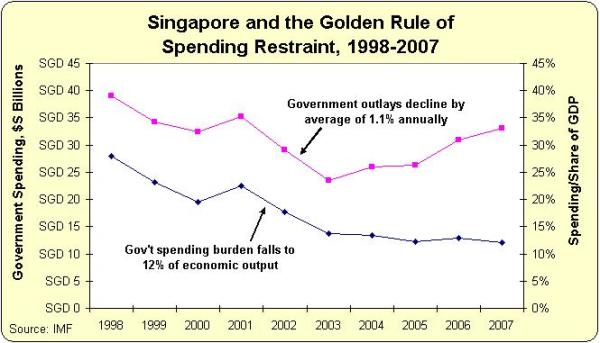

And the one time government spending climbed significantly about 20 percent of GDP (during the Asian financial crisis), the government then did a remarkable job of implementing the Golden Rule of spending restraint.

Singapore’s fiscal discipline between 1998 and 2003 was particularly impressive as spending was cut (genuine cuts, not the make-believe cuts you find in Washington) by an average of 9 percent each year.

But the statistic that matters most is that the burden of government spending dropped to 12 percent of GDP by 2007, a reduction of almost 16 percentage points (even larger than Sweden’s budget cutting between 1992 and 2001).

Government spending in Singapore has since 2007 slowly climbed back to about 18 percent of economic output, but that’s still quite good by modern standards (though much larger than government was in America back in the 1800s and early 1900s).

Let’s close by preemptively dealing with the statist argument that relatively small government somehow prevents the provision of genuine public goods.

Earlier this month, I shared some remarkable data from a study published by the European Central Bank. That research showed that “countries with small public sectors report the ‘best’ economic performance” and also receive the highest scores for providing public goods in a cost-efficient manner (referred to as “public sector efficiency”).

Looking at country groups, “small” governments post the highest efficiency amongst industrialised countries. Differences are considerable as “small” governments on average post a 40 percent higher scores than “big” governments. …This illustrates that the size of government may be too large in many industrialised countries, with declining marginal products being rather prevalent.

But as part of that post, I groused that the researchers were only looking at OECD member nations. Yet none of those countries have small public sectors.

I can’t help but wonder what the results would have been if Hong Kong and Singapore also were added to the mix. After all, I don’t consider the United States to have a “small” government. Same for Japan, Switzerland, and Australia. Those are simply nations where government isn’t as big and bloated as it is in France, Italy, Sweden, and Greece.

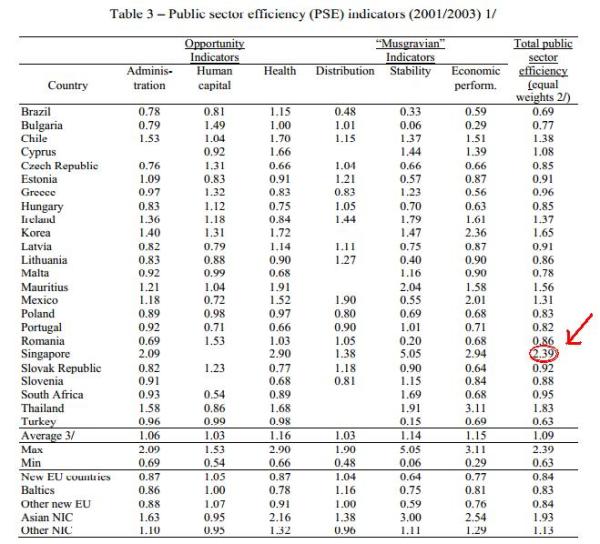

Well, I’m happy to report that I found another study from the European Central Bank that broadens the net to include some nations from Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America.

Singapore was one of the nations in the study and you won’t be surprised to learn that it received the highest score for “public sector efficiency.” But not merely the highest score, Singapore’s 2.39 was dramatically higher than the scores in the earlier study for the nations that supposedly had “small” governments (even though the actual burden of government spending in those countries is almost two times larger than it is in Singapore).

So what’s the bottom line?

The first ECB study clearly concluded that “small” government is more efficient and productive than either “medium” government or “big” government.

Based on the second ECB study, we can conclude that it’s even better if government is…well, I guess we’ll have to use the term “smaller than small.”

So congratulations to Singapore for readjusting the rankings. Now if we can find a jurisdiction where government consumes just 5 percent of GDP, we’ll be able to complete the research and finally figure out the “correct” size of government.