May 2011, Vol. XI, Issue I

Monitoring the OECD’s Campaign Against Tax

Competition, Fiscal Sovereignty, and Financial Privacy:

Strategies for Low-Tax Jurisdictions

The Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has an ongoing anti-tax competition project. This effort is designed to prop up inefficient welfare states in the industrialized world, thus enabling those governments to impose heavier tax burdens without having to fear that labor and capital will migrate to jurisdictions with better tax law. This project received a boost a few years ago when the Obama Administration joined forces with countries such as France and Germany, which resulted in all low-tax jurisdictions agreeing to erode their human rights policies regarding financial privacy. The tide is now turning against high-tax nations – particularly as more people understand that ever-increasing fiscal burdens inevitably lead to Greek-style fiscal collapse. Political changes in the United States further complicate the OECD’s ability to impose bad policy. Because of these developments, low-tax jurisdictions should be especially resistant to new anti-tax competition initiatives at the Bermuda Global Forum.

By Daniel J. Mitchell and Brian Garst

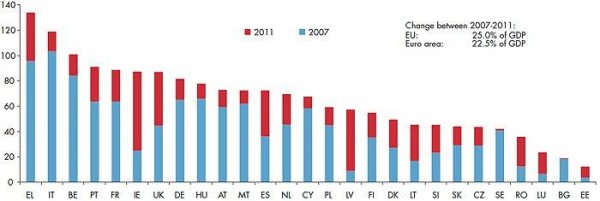

The next chapter in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) campaign against tax competition will take place at the Global Tax Forum in Bermuda, May 31-June 1, 2011. The OECD, dominated and controlled by European welfare states, has been working for more than a decade to impose punitive international tax rules in order to prop up the inefficient policies of member nations such as France and Greece. This illiberal effort is now being pursued with even greater urgency because politicians from those nations hope to find new revenue sources to postpone the inevitable collapse of their bankrupt and corrupt fiscal systems.

Current status

Unfortunately, high-tax nations have made progress on their anti-tax competition efforts in the past few years. Low-tax jurisdictions, faced with direct and indirect threats of sanctions from powerful nations, have been forced to weaken their human-rights policies by agreeing that privacy laws no longer protect foreign investors. Indeed, jurisdictions are being coerced to sign tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs) to provide confidential data upon request to high-tax OECD countries.

Expanding the network of these so-called information-exchange-agreements (a bit of a misnomer since the information flow is in one direction) is a major goal of this year’s forum. Simply stated, high-tax nations want the ability to impose higher tax rates on income that is saved and invested, and this means they are demanding other jurisdictions help them in their efforts to track – and tax – flight capital.

This effort undermines good tax policy, which is based on common-sense principles such as low tax rates, no tax bias against saving and investment, and territorial taxation. Ironically, the OECD’s economists agree on these principles of good tax policy, which strips away even the pretense of any intellectual justification for the anti-tax competition scheme being pushed by the OECD’s Fiscal Affairs Committee. For instance:

- The OECD has acknowledged that, “The overall tax burden is found to have a negative impact on output per capita. Furthermore, controlling for the overall tax burden, there is an additional negative effect coming from an extensive reliance of direct taxes.”1

- Another OECD study confessed that it is very misguided to double-tax saving and investment, noting, “Any taxation of capital income, however, represents a significant departure from the neutrality of taxation over time, favouring present over future consumption.”2

- And other study from the OECD stated, “Taxation of capital income, rather than the taxation of the consumption from that income, introduces a bias into the tax system. It ensures that the eventual consumption that flows from saving, over time, is less than that obtained by consuming immediately.”3

- Ironically, even an anti-tax competition manifesto published by the OECD admitted that, “The more open and competitive environment of the last decades has had many positive effects on tax systems, including the reduction of tax rates and broadening of tax bases which have characterized tax reforms over the last 15 years. In part these developments can be seen as a result of competitive forces that have encouraged countries to make their tax systems more attractive to investors. In addition to lowering overall tax rates, a competitive environment can promote greater efficiency in government expenditure programs.”4

The high-tax nations that dominate the OECD don’t care about good policy, however. The politicians from those countries simply want more tax revenue in hopes of postponing the day of reckoning. This point is evidenced by the recent agreement between Swiss authorities and the UK to “regularize” British funds in Swiss banks by taxing them at a 50% rate. The UK authorities were more than willing to drop their original goal of eliminating financial privacy in return for an injection of revenue. But like the drug addict, it won’t be long before they need their next fix.5

The key issue, for advocates of good tax policy, is how to prevent the high-tax nations from making more progress in their efforts to create a global tax cartel. That means guarding against schemes to expand the OECD’s power. The 2010 Global Forum in Singapore was uneventful, but the OECD did spring the “Mexico City Surprise” at the 2009 Forum in an attempt (fortunately unsuccessful) to give the OECD broad authority to attack tax avoidance and other legal forms of tax planning.

Why the campaign against tax competition will never cease: theory and reality

The OECD’s disingenuous stunt in 2009 should not have been a surprise. The politicians from high-tax nations who control the OECD are guided by bad theory and motivated by an unending appetite for more tax revenue.

The bad theory is CEN, which is an abbreviation for “capital export neutrality.” CEN refers to an ideological notion, taught by left-wing law professors, that taxpayers should never be allowed to benefit from better tax policy in other jurisdictions. OECD bureaucrats (as well as officials from finance ministries and finance departments in high-tax nations) are heavily influenced by the CEN mindset and this leads them to support policies designed to hinder all forms of tax competition.

From the perspective of CEN, any form of tax planning is illegitimate. Tax avoidance is just as bad as tax evasion. This is why the “Mexico City Surprise” should not have been a surprise. Adherents of CEN want to eliminate all forms of tax planning and create – for all intents and purposes – a tax cartel. From an economic perspective, this inevitably leads to an “OPEC for politicians.” Except instead of a price-fixing agreement, it would be a tax-fixing cartel.

Politicians, of course, have no understanding of the theoretical issues. A common joke in the tax community is that most elected officials couldn’t even spell CEN. They simply want more tax revenue to buy more votes, and these base impulses are particularly acute as they all face some level of Greek-style fiscal chaos in the near future. Fiscal forecasts and analyses by the OECD, EU, IMF, and private entities paint the same grim picture. Most European nations have taxed and spent themselves into fiscal cul-de-sacs, and the anti-tax competition effort is an endeavor to buy more time before the house of cards collapses.

The next steps

The OECD has its own version of the Brezhnev Doctrine (“what’s mine is mine; what’s yours in negotiable”). Now that low-tax jurisdictions have been coerced into signing TIEAs, the Paris-based bureaucracy almost certainly will expand its demands. Low-tax jurisdictions should be fully aware of the OECD’s bad-faith approach. Some policy makers from these jurisdictions are being duped into thinking they are “partners” with the OECD and that signing TIEAs will end the harassment from high-tax nations.

This is a triumph of hope over reality. There’s an old saying that feeding your leg to a crocodile does not turn him into a vegetarian. The same is true about appeasing the OECD. Just as a crocodile will come back for another meal, the opponents of tax competition will put forth new demands.

The following policies are the most immediate areas of concern.

1. Automatic information sharing.

The current system of TIEAs allows high-tax nations to request information about specific taxpayers if there is some reason to suspect they are investors in low-tax jurisdictions. It is quite likely that this system will not generate the desired windfall of new tax revenue. This is largely because estimates of foregone tax revenue are wildly exaggerated, but the OECD and its allies will argue that the “upon-request” model is inadequate and begin to push for automatic information sharing. This, of course, raises all sorts of concerns regarding data integrity, identity theft, misuse of information, and human rights abuses. And it would mean very high costs imposed on low-tax jurisdictions.

2. Attack on tax planning and tax avoidance

The “Mexico City Surprise” failed in 2009, but that does not mean the OECD and high-tax nations will let the issue drop. The Capital Export Neutrality theory makes no distinction between tax evasion and tax avoidance. Revenue-hungry politicians also don’t care whether they are missing out on potential tax revenue because of legal or illegal actions. There is an assumption that substantially more tax can be collected from both rich people (high net worth individuals, or HNWIs) and corporations (particularly multinationals), and that this will require coordinated action. This would lead to much higher compliance burdens on targeted taxpayers, but also costly new rules and reporting regimes for low-tax jurisdictions.

3. Global financial taxes

There is a drumbeat for some sort of worldwide financial tax. In some cases, advocates envision a global tax, perhaps imposed and collected by an international bureaucracy. The Tobin Tax would be one example of this approach. In other cases, proponents urge bank taxes imposed on a country-by-country basis, but with some sort of agreement that all jurisdictions participate since a tax cartel is needed to prevent investors/depositors from shifting funds across national borders. This latter approach often is characterized as a response to bailouts, either to recoup funds already spent or to accumulate funds for potential future bailouts. Regardless of the design, and regardless of the stated reason for the tax, politicians from high-tax nations are salivating at the thought of additional revenue. Imposing new costs on the “offshore” world would be a fringe benefit, sort of akin to icing on a cake.

4. Savings tax directive, part II

The European Union already has implemented a version of automatic information sharing, but the politicians are very unhappy with the system because it does not apply to all forms of capital income and asset accumulation and because some of the participating nations (all EU countries, plus a handful of non-EU jurisdictions) can choose a withholding tax instead. This system has not generated the desired (and hopelessly unrealistic) level of new tax revenue, so there are discussions about how to expand the scope of the directive – including a scheme to ensnare more jurisdictions into the cartel. This is a non-OECD issue, but rest assured it will be in the minds of all European representatives at the Bermuda meeting.

5. Formula apportionment of business income

Proponents of tax harmonization would like all nations to impose identical tax regimes. Such an approach would, by definition, eliminate tax competition and give politicians from all nations a common ability to increase tax rates. And it is the logical end point for proponents of the Capital Export Neutrality theory. A direct attack on fiscal sovereignty is not plausible in the current environment, however, so advocates hope to gain a partial victory by harmonizing the tax base (i.e., the definition of taxable income) and then dividing up a company’s profits based on some sort of formula based on sales, employment, and/or assets. The European Commission is pushing for such an approach (the common consolidated corporate tax base), and many on the left are urging that this system be imposed on a global basis. The motive for this approach is that companies earn a “disproportionately” large share of their profits in low-tax jurisdictions. But if there was some sort of harmonized tax base, perhaps imposed in a might-makes-right fashion by big nations, then a formula could be used that would unilaterally turn profits earned in so-called tax havens (as well as places such as Hong Kong, Switzerland, Ireland, Slovakia, and China) into taxable income for Germany, France, Japan, and the United States. This would dramatically undermine incentives to invest in jurisdictions with better tax policy and lead to a significant increase in the corporate tax burden.

6. Worldwide taxation

Worldwide taxation refers to the practice of nations taxing things that occur outside their borders, and the United States has the worst worldwide tax system of any nation. Most jurisdictions at least attempt to impose double taxation on individual capital income (dividends, interest, and capital gains) on a worldwide basis, and the United States certainly is in this category. But the United States is an outlier in that it also imposes worldwide taxation on corporate income. And it is virtually alone in taxing the labor income of citizens who live and work abroad. Indeed, the United States actually restricts the right of emigration, imposing punitive exit taxes (disgracefully reminiscent of the policies of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia) on people who want tax residency in other jurisdictions. Other nations rely much more on territorial taxation, but not because of an affinity for good tax policy or respect for human rights. Instead, their tax authorities don’t have the long reach and unchecked power of the IRS. But as privacy gets eroded and it becomes easier for other nations to track economic activity across the globe, the temptation will grow to copy America’s bad approach. Politicians from high-tax nations would love to retain taxing power over companies and individuals that move to places such as Hong Kong, Switzerland, Cayman, Panama, Monaco, Singapore, etc. If they succeed, this would dramatically reduce incentives to move to jurisdictions with better tax law and (because of the crippling impact on tax competition) facilitate big increases in tax rates.

7. National Blacklists

To augment the OECD attack on low-tax jurisdictions, some governments have created national blacklists. This usually means a high-tax nation will impose a law that specifically identifies “tax havens” and imposes restrictions on economic relations. Discriminatory withholding taxes are sometimes imposed, and there also can be restrictions on doing business with companies domiciled in the targeted low-tax jurisdictions.

These national efforts, to be sure, are not an official part of the OECD’s anti-tax competition campaign. But it is rather revealing that low-tax jurisdictions are targeted – even if they are “participating partners” in the OECD’s global forum. If the bureaucrats in Paris and the high-tax nations that dominate the OECD actually believed in a fair process, these national blacklists would be forbidden.

It is impossible to say which, if any, of these proposals will be discussed at the Bermuda Global Forum. With any luck, none of these issues will get on the agenda. But that is just a matter of timing. Sooner or later, politicians from high-tax nations will pursue some or all of these policies. And since the OECD is a tool of those high-tax nations, it is quite likely that a Global Forum will be the vehicle for continued assaults on tax competition, fiscal sovereignty, and financial privacy.

What should low-tax jurisdictions do?

Prior to the 2008 election, the American government had a policy of benign neglect regarding the OECD’s anti-tax competition project. This was very helpful. After all, just as OPEC would be feeble without the participation of Saudi Arabia, a global tax needs U.S. support. Ever since the 2008 elections, however, the United States government has been aligned with Europe’s welfare states. This unfortunate development largely explains why the OECD was able to go back on offense and coerce low-tax jurisdictions into agreeing to upon-request TIEAs.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that the Obama Administration recently suffered a sweeping repudiation in the mid-term elections. There is now a divided government, as Republicans control the House of Representatives.

This has important implications for the tax competition battle. The Coalition for Tax Competition, led by the Center for Freedom and Prosperity and comprised of various taxpayer organizations, think tanks, and free market groups, is coordinating a much more concerted effort to reduce the huge subsidy that American taxpayers provide to the OECD. Because of the backlash among voters against excessive government spending, and because Republicans feel they have to prove that they “got the message” after losing the last two elections due to profligate spending during the Bush years, there is a much more receptive climate for the Coalition’s anti-OECD message.

So what does this mean? The OECD is like every other government bureaucracy. The first imperative is more money and more staff. And OECD bureaucrats know they have a very comfortable scam. Not only do they receive above-market compensation, but they also are exempt from paying any tax on their overly-generous incomes (yes, it goes without saying that it is ironic that tax-free bureaucrats get to jet-set around the world seeking to raise taxes on everybody else).

With Republicans now in control of the House of Representatives, it is an open question whether the OECD will be able to maintain an aggressive anti-tax competition campaign. Direct and indirect pressure is growing for the Paris-based bureaucracy to ease up on the big-government agenda.

In response to the anti-OECD message, one budget proposal submitted by several dozen members of the House even included a complete cut of OECD funding. Other divisions of the Paris-based bureaucracy will hopefully learn from this that their gravy train may get derailed because of the actions of the Committee on Fiscal Affairs, so there will be significant internal pressure to be more rational.

From the perspective of low-tax jurisdictions, it remains critical that the OECD and high-tax nations not be allowed to ram through any new initiatives before this pressure can fully materialize. The clock is not on their side, so it is imperative to block the OECD from any schemes designed to accelerate the process. In addition, low-tax jurisdictions can help solidify a reversal of the decades-long trend toward big-government by beginning to speak up and raise their objections to the process.

Speak Up And Fight Back

The OECD and high-tax jurisdictions count on quiet acquiescence from their low-tax counterparts. So long as low-tax jurisdictions are intimidated and shamed into rolling over and playing dead, the process of eroding fiscal sovereignty will continue to advance.

If the constant moving of the goal posts has proven anything, it is that appeasement is not a viable strategy. By speaking up and aggressively defending the superiority of their tax policies on both fiscal and moral grounds, low-tax jurisdictions can force those driving the agenda to have to choose between openly displaying their contempt for the interests of the jurisdictions that they are seeking to saddle with bad tax policy, or allowing the process to hoist them with their own petard.

While standing up for themselves is the preferred strategy for low-tax jurisdictions, even the simple act of talking more can serve an important function by forcing OECD bureaucrats and delegates from high-tax nations to address key issues. If nothing else, this can be useful because where there is substantial disagreement between large and small states, the OECD chair needs time to ‘wind down’ the objections of the speakers before moving on. If there is no winding down, issues either get tabled or the position of the small countries is conceded.

Speaking up also helps solve the false consensus problem. Often times, issues are agreed to simply because no one objects, making it seem as if there is greater consensus than there really is. One way to get the ball rolling in preventing false consensus from building against low tax jurisdictions is to ask questions. It’s quite likely that the large jurisdictions will respond with objectionable answers, thus giving other jurisdictions reason to speak up, and help thwart the false consensus the OECD seeks to create. However for this to happen, countries must speak up. The Forum is depending on countries to stay in line. Combating the consensus building can be a powerful tool, as it relies on an absence of dissenting voices. Any dissenting voice must be responded to.

The problem, of course, is that low-tax jurisdictions are concerned that they will be singled out for discriminatory and unfriendly attention if they make comments. There is a widely shared perception, for instance, that the OECD is using the “peer review” evaluations for precisely this purpose.

A number of low tax jurisdictions have already received ‘deficient’ phase I evaluations. These evaluations give these countries reason to speak up. After all, there’s no point in being compliant if you’ve already been mistreated.

But other jurisdictions should add their voices. If a sufficient number point out the flaws in the process, it becomes very difficult for OECD nations to engage in retribution.

Indeed, the key recommendation of this paper is that officials from low-tax jurisdictions have nothing to lose by being more assertive. Officials from Barbados, for instance, have been rather vocal at times in their reaction to bad-faith behavior by the OECD.6 Has this put them in any worse position than other persecuted jurisdictions? Panama officials also have been somewhat vocal and this has not resulted in any additional harassment.

The OECD and high-tax nations want to put smaller jurisdictions out of business, and meek responses encourage rather than discourage this destructive mentality. Some representatives from low-tax jurisdictions privately complain that it is too risky to make noise. But this don’t-raise-your-head-above-the-foxhole approach is a recipe for gradual extinction.

Fighting for Prosperity and Opportunity

Part of the OECD’s strategy has been to imply that low-tax jurisdictions are rogue regimes that somehow threaten the global economy. This is why they have striven to make “tax haven” a negative term. And remember when politicians from high-tax nations asserted the financial crisis somehow was caused by “hot money” from tax havens? Even gullible journalists quickly realized that was an absurd assertion.

It’s time to regain the offensive. The high-tax nations are the rogue regimes. They are the nations with unsustainable fiscal policy. Places such as Greece, Spain, Italy, and France are examples of high-tax nations that will destabilize the world economy by causing sovereign debt crises. OECD nations are the ones with punitive tax systems that undermine growth.

Tax havens and other low-tax jurisdictions are outposts of fiscal sanity – at least relatively speaking. Yes, they periodically fall into bad habits and let government get too big and spend too much, but at least they’re subject to the discipline of global markets and can’t bury their heads in the sand and cross their fingers that big new sources of revenue will be magically forthcoming.

The world would be a much better place if OECD nations copied the fiscal policy of tax havens, not vice versa.

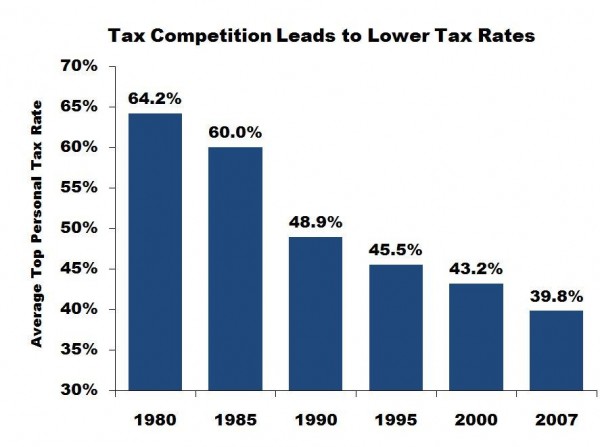

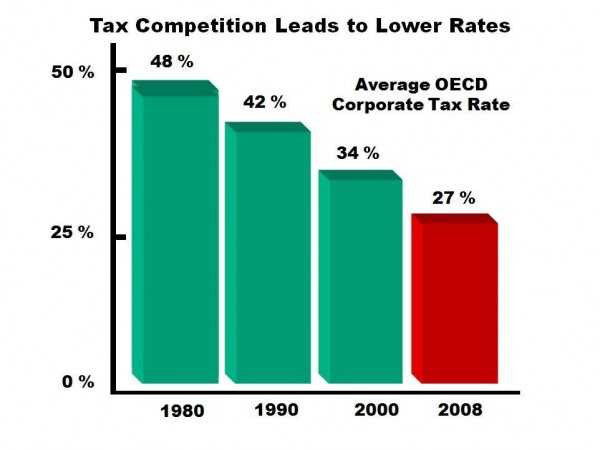

Tax competition means better policy

Low-tax jurisdictions generally are the ones with good tax policy. There is wide agreement among public finance economists that an ideal tax system should be based on low tax rates, no double taxation, no loopholes, and territoriality. Yet the OECD’s anti-tax competition effort is designed to help high-tax nations impose double taxation on an extraterritorial (or worldwide) basis.

This is why economists tend to be strong supporters of competition between jurisdictions. Tax competition encourages nations to adopt good tax policy, even if politicians from those countries would prefer to adopt class-warfare policies because of perceived short-run electoral considerations.

Conclusion

No matter what the high-tax lobby claims, the anti-financial privacy agenda is not being pushed to benefit low-tax jurisdictions. They will make that claim, but it is nothing more than the bait intended to lure the next prey on which they will feast. As we have shown, the stark reality is that all of these efforts are being undertaken to identify additional sources of revenue to prop-up, even if only temporarily, the high-tax welfare states.

In order to help facilitate the process of defending low-tax jurisdictions, CF&P is willing to confer privately with interested jurisdictions and offer our expertise. We will also be available at the Bermuda Global Forum to meet with delegates.

Finally, rather than reiterate the main points in a conclusion, the best way to end this paper is with a series of quotes from Nobel laureates. These economists understand that a cartel of high-tax nations would be a mistake. An “OPEC for politicians” would hurt the global economy and condemn people around the world to a more dismal future.

“…competition among nations tends to produce a race to the top rather than to the bottom by limiting the ability of powerful and voracious groups and politicians in each nation to impose their will at the expense of the interests of the vast majority of their populations.”

Gary Becker

“…tax competition among separate units…is an objective to be sought in its own right.”

James Buchanan

“Competition among national governments in the public services they provide and in the taxes they impose is every bit as productive as competition among individuals or enterprises in the goods and services they offer for sale and the prices at which they offer them.”

Milton Friedman

“…international competition provided a powerful incentive for other countries to adapt their institutional structures to provide equal incentives for economic growth and the spread of the ‘industrial revolution.’”

Douglas North

“Competition among communities offers not obstacles but opportunities to various communities to choose the type and scale of government functions they wish.”

George Stigler

“[Tax competition] is a very good thing. …Competition in all forms of government policy is important. That is really the great strength of globalization …tending to force change on the part of the countries that have higher tax and also regulatory and other policies than some of the more innovative countries. …The way to get revenue is doing all you can to encourage growth and wealth creation and then that gives you more income to tax at the lower rate down the road.”

Vernon Smith

“With apologies to Adam Smith, it’s fair to say that politicians of like mind seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise taxes. This is why international bureaucracies should not be allowed to create tax cartels, which benefit governments at the expense of the people.”

Ed Prescott

“[I]t’s kind of a shame that there seems to be developing a kind of tendency for Western Europe to envelope Eastern Europe and require of Eastern Europe that they adopt the same economic institutions and regulations and everything. …We want to have some role models… If all these countries to the East are brought in and homogenized with the Western European members then that opportunity will be lost.

Edmund Phelps

Endnotes

1 Andrea Bassanini and Stefano Scarpetta, “The Driving Forces Of Economic Growth: Panel Data Evidence For The OECD Countries,” OECD Economic Studies No. 33, November 2001. Available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/2/18450995.pdf.

2 Richard Herd and Chiara Bronchi, “Increasing Efficiency and Reducing Complexity in the Tax System in the United States,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 313, December 2001, available at http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/increasing-efficiency-and-reducing-complexity-in-the-tax-system-in-the-united-states_641187737504.

3 Economic Survey of the United States, 2001, available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/47/31/2673115.pdf.

4 OECD, ‘The OECD’s project on harmful tax practices: the 2001 progress report’ (the ‘2001 report’), Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/60/28/2664438.pdf.

5 Vanessa Houlder, “Britons to be taxed on secret billions,” Financial Times, May 2, 2011, available at http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/6b4f2fb2-74da-11e0-a4b7-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1MmbynbCd

6 “Barbados: Government’s Assault on The OECD.” Press Release, available at http://www.caribbeanpressreleases.com/articles/8195/1/Barbados-Governments-Assault-On-The-OECD/Page1.html.