February 2008, Vol. VIII, Issue I

The Global Flat Tax Revolution:

Lessons for Policy Makers

Thanks largely to tax competition, governments are dramatically improving tax policy. Over the past 30 years, tax rates on productive activity have been sharply reduced. Personal and corporate income tax rates have been slashed. Capital gains tax rates, wealth taxes, and death taxes have been lowered or eliminated. These pro-growth reforms have boosted the global economy, lowered poverty, and improved living standards.

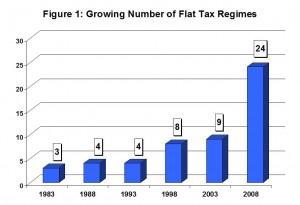

Perhaps the most exciting development, though, is the flat tax revolution. The number will probably be higher by the time you are reading this, but as this article went to press, 24 nations have adopted some form of single-rate tax regime. These reforms have generated impressive results, including faster growth, more jobs, and increased competitiveness. While politicians generally are most concerned about losing tax revenue, they should not worry. Flat tax systems oftentimes generate higher tax revenues because of more income and better compliance.

The economic consequences of tax reform are positive, but the political implications also are profound. Governments are deciding – in part because labor and capital can cross national borders to escape punitive tax rates – that it no longer makes sense to discriminate against highly-productive taxpayers. Thanks to tax competition, expect the number of flat tax countries to continue to grow.

By Daniel J. Mitchell

Thirty years ago, the average top personal income tax rate in industrialized nations was more than 65 percent, and the average corporate tax rate was nearly 50 percent. Double taxation of dividends and capital gains was ubiquitous, and most nations taxed income a third time with either death taxes or wealth taxes-or sometimes even both. Not surprisingly, economic stagnation was common, and policy debates focused on how to divide a shrinking pie.

Today, the world of fiscal policy is profoundly different. Beginning with “radical” reforms implemented by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, governments across the globe have been racing to lower tax rates on productive behavior. Personal and corporate income tax rates have been dramatically reduced, and the tax burden on saving and investment has been lowered.

In a growing number of nations, the debate now is focused on fundamental tax reform. A fiscal revolution is taking place and 24 jurisdictions now have flat tax regimes (Figure 1). The only question now seems to be is how many new nations will join the flat tax club with each passing year.

This flat tax revolution is changing the world. Jurisdictions with the most aggressive and far-reaching single-rate tax systems, such as Estonia, Hong Kong, and Slovakia, are enjoying rapid economic growth. Flat tax systems also are leading to more revenue in many cases, reaffirming the Laffer Curve notion that reasonable tax rates and strong economic growth are the best way to generate monies for government. Perhaps most important, the flat tax revolution signifies a victory over the notion that the tax code should be used to penalize those who contribute most to economic growth. The ultimate irony is that this revolution in both economic and moral attitudes is being led by nations in Central and Eastern Europe-countries that were part of the Communist Bloc less than two decades ago.

Thanks to tax competition, it is likely that the list of flat tax nations will continue to expand. Because the geese that lay the golden eggs can more easily fly across the border, globalization is putting pressure on politicians to lower tax rates and reform tax systems. Nations that adopt flat taxes are attracting jobs and capital from uncompetitive high-tax nations. Perhaps after France relents and implements tax reform, a flat tax will even be adopted in the United States.

What is a Flat Tax?

The pure flat tax system is based on the proposal put forth by Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. Hall and Rabushka brought the concept of the flat tax to national attention in a 1981 Wall Street Journal article and later in a 1983 book (which has been updated).1 Casual observers frequently associate flat tax plans with radical simplification, but postcard-sized tax returns are the potential result-not the cause-of the pro-growth components of a flat tax. These positive features include:

- A Single Flat Rate. The flat tax has a single rate, and the goal is to bring the rate down as low as possible, usually less than 20 percent. The low, flat rate reduces penalties against productive behavior, such as work, risk taking, and entrepreneurship.

- Elimination of Special Preferences. The flat tax eliminates provisions of the tax code that create tax advantages for certain behaviors and activities. Getting rid of deductions, credits, exemptions, and other loopholes promotes growth both by allowing a low tax rate and by removing incentives to misallocate resources merely to reduce tax liability.

- No Double Taxation. Flat tax proposals are based on the principle that income should be taxed only one time. This means no death tax, no wealth tax, no capital gains tax, no double taxation of saving, and no double tax on dividends. Eliminating the tax code’s bias against capital formation is conducive to job creation and capital formation.

- Territorial Taxation. The flat tax is based on the common-sense notion of “territorial taxation,” meaning that governments only tax income that is earned inside national borders. Getting rid of “worldwide taxation” simplifies the tax system, promotes international comity, and enables taxpayers and companies to compete on a level playing field around the world.

The flat tax has other selling points, including transparency (it is difficult to swap campaign cash for special tax breaks when the tax system is based on two postcards) and generous personal allowances based on family size. These features are politically important, but the economic benefits of fundamental reform result from the above factors-particularly the low tax rate on productive behavior and the end to tax code biases based on the source of income, use of income, or level of income.

The Flat Tax Sweeping the World

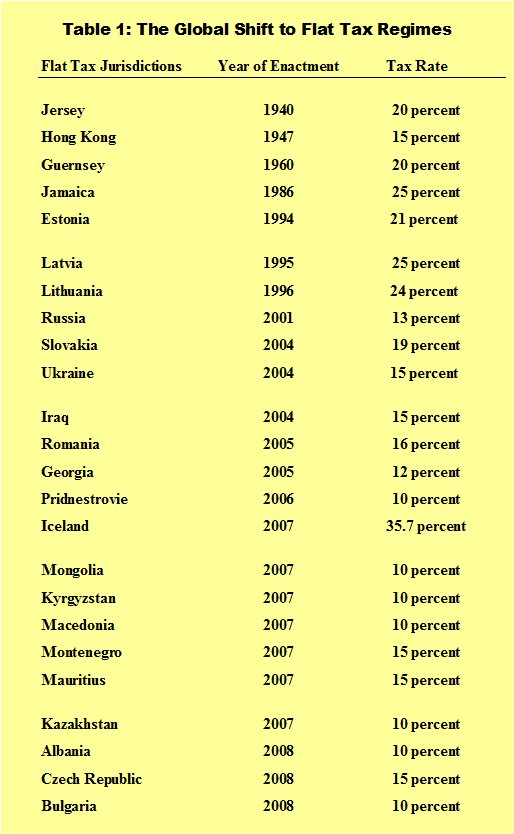

Single-rate tax systems have suddenly become very popular. Up until 1994, the only jurisdictions with flat tax systems were Hong Kong, two other (very obscure) British territories-Jersey and Guernsey, and Jamaica. Today, by contrast, there are 24 flat tax systems. With just a handful of exceptions, the new flat tax jurisdictions are former Soviet Republics or Soviet Bloc nations.2 But Iceland’s shift to a flat tax in 2007 is a key development since it shows that tax reform is possible in a mature and prosperous democracy.

The shift to flat taxes is dramatic. For decades, critics said a flat tax was unrealistic and that Hong Kong was a special case. They never explained why it was a special case, but supposedly a flat tax could not work anyplace else. They made similar assertions after the Baltic nations adopted flat tax systems, but adapted their arguments to suggest that a flat tax only worked in small jurisdictions. But then when Russia and other large Eastern European nations hopped on the flat tax bandwagon, opponents began to concede that flat tax regimes were feasible, but rationalized that tax reform worked only in transition economies. Now that Iceland has a flat tax, one can only imagine the new excuses that will be used to argue the flat tax does not work or that it is impractical.

If imitation is the highest form of flattery, the flat tax certainly is getting lots of praise. The flat tax revolution is especially remarkable because so many wanted to dismiss it as a fad. Indeed, as recently as 2006, an International Monetary Fund study boldly stated that, “Looking forward, the question is not so much whether more countries will adopt a flat tax as whether those that have will move away from it.”3 Yet within months of the IMF study being released, as seen in Table 1, several new nations were part of the flat tax club – and several more nations hopped on the flat tax bandwagon this year. The international bureaucracy’s powers of prediction certainly leave much to be desired, both because the study was wrong about whether more nations would adopt flat taxes, but also because the speculation about countries moving in the other direction proved false as well.

The durability of the flat tax is just one of several noteworthy observations about the flat tax revolution.

- Nations are choosing low-rate flat taxes. With the exception of Iceland, every flat tax adopted this decade has a tax rate of less than 20 percent. This is important since the economic benefits of a flat tax are directly linked to the reduction in marginal tax rates on productive behavior. In the mid-1990s, the Baltic flat taxes had rates ranging between 25 percent and 33 percent. While these rates were much better than the confiscatory levies imposed by Western European nations, flat-tax rates above 25 percent are more likely to discourage work, saving, and investment than rates below 20 percent.

- Tax rates are dropping. Not only are new flat tax nations choosing low rates, nations that already have flat tax systems are reducing their rates. Estonia has dropped its rate from 26 percent to 21 percent, and the rate is scheduled to fall to 18 percent by 2011. Lithuania’s rate has fallen from 33 percent to 24 percent. Macedonia’s flat tax was just implemented at the low rate of 12 percent, but it already has dropped to 10 percent. Montenegro’s flat tax rate, meanwhile, will fall to 9 percent in 2010-giving it the lowest flat tax rate in the world.4

- More nations are considering the flat tax. The Czech Republic and Bulgaria are among the nations that just adopted the flat tax. Mauritius also just joined the flat tax club. Single-rate tax systems currently are being discussed in Poland and Hungary. There is even a growing interest in flat tax systems in Western Europe – a debate that presumably will intensify because of tax competition.

- No nation has returned to a so-called progressive tax. Notwithstanding faulty analysis from the IMF, the flat tax seems to be remarkably resilient. None of the flat tax nations have returned to a discriminatory rate structure. The most recent threats to single-rate regimes came in Russia, where lawmakers overwhelmingly rejected a scheme to create a progressive system with a top rate of 30 percent.5 More impressive, Slovakian voters in 2006 elected a coalition of socialists and nationalists, leading many to conclude that this did not bode well for the flat tax implemented by the outgoing government. Yet Slovakia’s new leaders decided not to tinker with the goose that was laying golden eggs and the flat tax seems securely enshrined.6

While the flat tax has become very trendy, it is not a cure-all for every economic ill. To maximize the economic benefits of tax reform, a nation should have the rule-of-law, property rights, sound money, limited government, and low levels of regulation. In such an environment, a flat tax ensures that the tax code will not be an obstacle to growth. In a nation such as Russia, however, a flat tax is going to have only limited success because people worried about arbitrary expropriation by the government are unlikely to feel confident about investing in the nation’s future. Likewise, the flat tax created for Iraq in 2004 is almost irrelevant to that country’s economic prospects because of ongoing turmoil.

Leading Flat Tax Systems

Not all flat tax systems are created equal. In some cases, such as Lithuania and Russia, there is a significant difference between the corporate rate (which is higher in Russia) and individual rate (which is higher in Lithuania), creating artificial incentives to manipulate how income is received. A gap in the rates is not a big issue if the difference is small and both rates are low-as in Hong Kong-but one of the goals of a flat tax is to encourage people to be productive without worrying about finding the best niche in the tax code. Last but not least, many flat tax nations fail to achieve the important goal of taxing income only one time.

While all 24 flat tax jurisdictions have features worthy of attention, there are a handful of flat tax regimes that are worth highlighting. There is no nation with a pure Hall-Rabushka two-postcard system, but many countries have done a remarkable job in creating tax codes that fulfill most or all of the major goals of a pro-growth tax system. These include:

i.) Hong Kong: Starting the Trend

Hong Kong has enjoyed a flat tax since 1947 and the system works so well that Hong Kong routinely is the world’s fastest growing economy. Indeed, growth is so robust that the government has just lowered flat tax rates to keep budget surpluses from becoming even bigger. As of April 1, 2008, Hong Kong taxpayers enjoy a low-rate optional flat tax of 15 percent on personal income.7 Taxpayers also can choose an alternative system with graduated rates, and the top rate in this system is just 17 percent. Interestingly, there is no withholding in Hong Kong, meaning that taxpayers pay their entire income tax liability themselves (usually twice a year). The corporate tax is not perfectly aligned with the personal tax, but the flat rate is just 16.5 percent, so the gap is very small. Hong Kong generally does not double-tax dividends, interest, and capital gains, so the system is very close to fulfilling the goal of taxing income only one time. Likewise, there is no death tax or wealth tax. Hong Kong also has a territorial system, so there is no second layer of tax on income earned by Hong Kong citizens in other jurisdictions.

Other features of the fiscal system are equally impressive. There are no payroll taxes in Hong Kong. Workers put 10 percent of their income into private retirement accounts. There also is not a general sales tax or value-added tax in Hong Kong. The entire tax code, even after being in place for 60 years, is only about 200 pages long. Because of the absence of other taxes, Hong Kong has a very low burden of government spending, at least by modern standards. Indeed, the budget consumes less than 20 percent of GDP. The Hong Kong fiscal system certainly has generated good results, such as:

- Hong Kong’s budget usually has a budget surplus and there is very little government debt. Indeed, the government has net surplus reserves.8

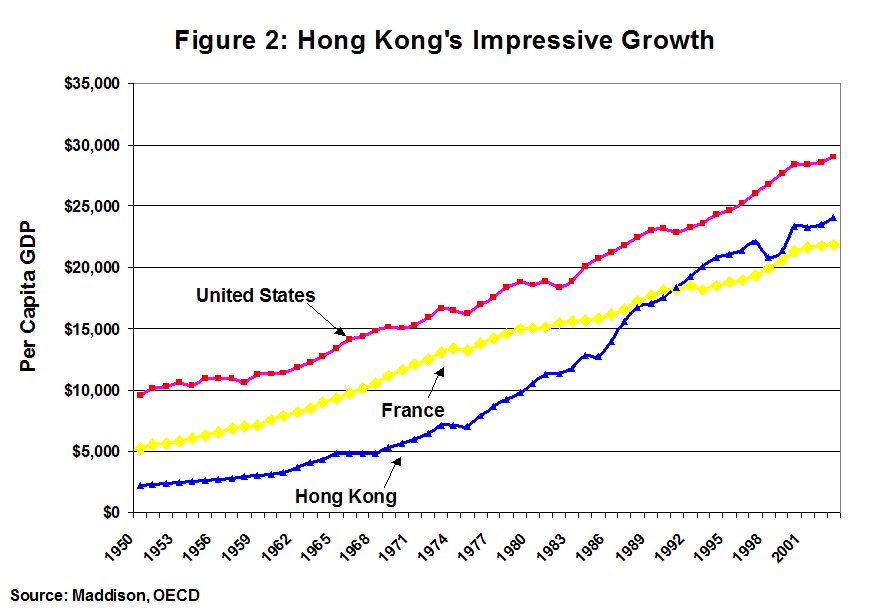

- Hong Kong has been one of the world’s fastest growing economies. Per capita income today is about $30,000, up from less than $2,000 after World War II.9 As shown in Figure 2, Hong Kong has surpassed France and has dramatically narrowed the income gap with the United States.

- The wealthy pay most of the tax in Hong Kong. The bottom 60 percent pay no income tax while the richest 100,000 taxpayers (the top 8 percent) pay 57 percent of the total tax burden.10

ii.) Estonia: Leading the Way for Ex-Soviet Bloc Nations

Estonia has a flat tax of 21 percent, and the rate keeps falling. When first implemented in 1994, the rate was 26 percent. By 2011, it will drop to 18 percent. The business rate also is 21 percent and it will drop in lock-step with the personal income tax rate, though it is important to understand that Estonia has, for all intents and purposes, eliminated the corporate income tax-at least as it is conceived in most other nations. Businesses merely impose a withholding tax of 21 percent on any dividends paid to owners. There is no double-tax on those dividends, and interest also is free from double taxation. There also is no death tax or wealth tax, so Estonia has done a good job of eliminating the tax bias against saving and investment. There is a capital gains tax, though individuals easily can avoid the tax by setting up companies to hold and manage investments.

Unlike Hong Kong, Estonia does have other taxes, including an onerous 29 percent payroll tax (technically 33 percent, but four percentage points go directly into a personal retirement account). Estonia also has a value-added tax of 18 percent. The payroll and VAT levies are substantial, which is why the overall burden of government in Estonia is approximately twice as high-as a share of GDP-as it is in Hong Kong. But this still means that government in Estonia is smaller than it is in most other European nations. And the presence of other taxes should not detract from the key achievement of the flat tax, which include:

- Economic growth, even after adjusting for inflation, has averaged nearly 9 percent over the past six years.

- The budget has been in surplus for the past six years because revenues are rising so quickly.11 Personal income tax revenues have doubled since 2000 and corporate revenues have jumped by about 300 percent during the same period.12

- Unemployment has dropped from more than 12 percent at the beginning of the decade to barely 6 percent today.13

iii.) Slovakia: The Slavic Tiger

Slovakia implemented a flat tax rate of 19 percent on January 1, 2004. The flat tax rate applies equally to labor income and business income. Most forms of double taxation have been abolished. Dividends paid to shareholders are not subject to a second layer of tax. As part of the reform, the death tax and gift tax were both abolished. There also is no wealth tax.

Like Estonia, other taxes are significant in Slovakia. The country has a 19 percent value-added tax. Payroll taxes are a significant burden. Counting both employee and employer shares, they are nearly 50 percent, though there is a cap on the amount of income subject to payroll taxes. Even with these onerous taxes, the aggregate tax burden in Slovakia is about 30 percent of GDP, down from a peak of 41 percent of GDP in 1993 and one of the lowest levels among developed nations. In addition to tax reform, Slovakia has implemented personal retirement accounts, liberalized labor markets, enacted school choice, and reformed the welfare system.

- The flat tax and other reforms have improved economic performance. Economic growth, after adjusting for inflation, has averaged 6.6 percent per year, and is projected to average nearly 8 percent in 2007-08.14

- The flat tax reform has generated a supply-side feedback effect. Because lower income tax rates stimulated additional productive behavior, personal income tax revenue collections in the first year were higher than forecasted by static revenue estimates. Likewise, value-added tax collections were lower than forecast in response to the generally higher tax rate.15

- Slovakia’s system is widely seen as a model for other nations, leading one economist to state, “The Slovak public finance reform will be studied in economic textbooks all over the world one day.”16

iv.) Iceland’s High-Rate Flat Tax

Iceland is an exception to the rule that flat tax systems have low tax rates. Beginning January 1, 2007, the island nation near the Arctic Circle has a 35.7 percent flat tax. While it is remarkable that a Nordic nation has chosen to abandon so-called progressive taxation, a system with a tax rate above the highest tax rate in the U.S. system is an outlier in the flat tax community. On the other hand, Iceland has significantly reduced the double taxation of income that is saved and invested. The corporate tax rate, for instance, is just 18 percent – and soon will fall to 15 percent. There is also a low tax rate of just 10 percent on various forms of capital income paid to individuals, such as dividends, interest, and capital gains. The death tax has been cut to 5 percent, and the wealth tax has been abolished.

Like other European nations, Iceland has an onerous value-added tax, in this case 24.5 percent. But payroll taxes are modest, totaling less than 6 percent.17 Nonetheless, the aggregate tax burden is sufficiently high to finance a government that consumes about 43 percent of national economic output. In addition to tax reform, Iceland also has adopted other market-based reforms, such as personal retirement accounts and privatized fisheries.18 Iceland’s flat tax is too new to draw any conclusions, but other policies to reduce the burden of government have played a salutary role:

- Thanks in part to market-oriented reforms, Iceland is now one of the world’s richest countries, ranking in the top 10 according to both methods used by the World Bank.19

- Unemployment is almost nonexistent, with fewer than 2 percent of the working-age population without a job.20

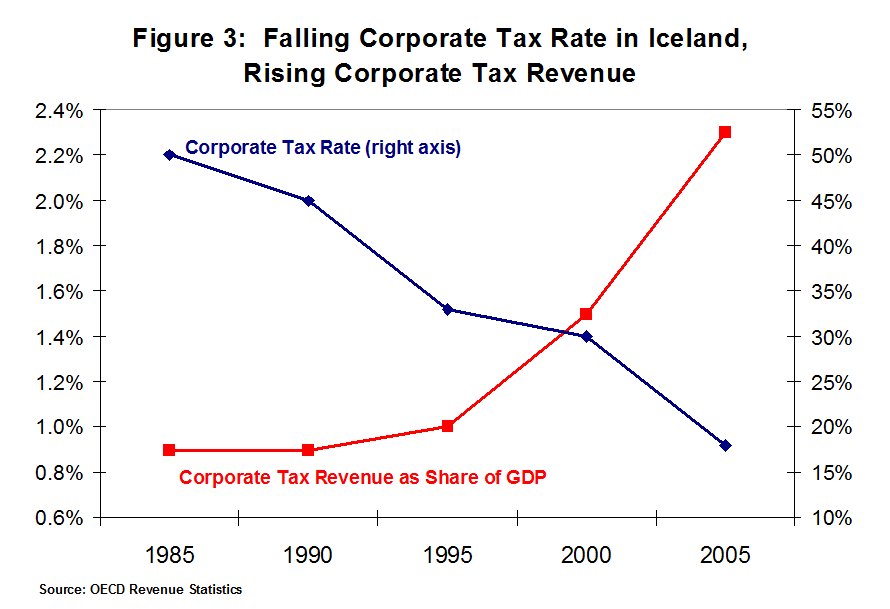

- The corporate tax rate has been dramatically reduced, yet revenues have climbed. As shown in Figure 3, corporate tax revenues have jumped significantly, rising from less than 1 percent of GDP to more than 2 percent of GDP.

Other Positive Results

Like Iceland, many of the flat tax systems are so new that it is difficult to draw conclusions, but some flat tax systems have been in place long enough to show positive effects. To augment the earlier discussion of Estonia, the World Bank reports that the three flat tax Baltic nations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are the richest nations of all the former Soviet Republics.21 The IMF, meanwhile, reports that GDP in the three Baltic nations increased by 9.0 percent in 2005 and 9.7 percent in 2006-and projects growth to average nearly 8 percent in 2007 and 2008.22

Slovakia’s flat tax also was discussed earlier, but the results are even more impressive when compared to other Eastern European nations. The IMF, for instance, reports that Slovakia is growing faster than the Czech Republic, and is expected to continue growing faster-by nearly three percentage points annually-over the next couple of years.23 The key difference: Slovakia has had a flat tax since 2004 whereas Czech lawmakers waited until 2008 to implement a simple and fair tax system. Romania is another positive story. The economy has been expanding by about 6 percent each year, and the IMF expects the trend to continue-an impressive performance compared to nearby non-flat tax jurisdictions such as Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, and (prior to this January) Bulgaria.24

Georgia is another success story. Its 12 percent flat tax went into effect in 2005 and annual growth has averaged 9 percent since then, and the IMF expects growth to remain high at about 7 percent for the next two years.25 But Georgia is not resting on its laurels. It has now combined the 12 percent flat tax and 20 percent payroll tax into a combined 25 percent tax – a seven percentage-point reduction in the combined tax rate, and it intends to lower this combined tax to just 15 percent over the next five years.

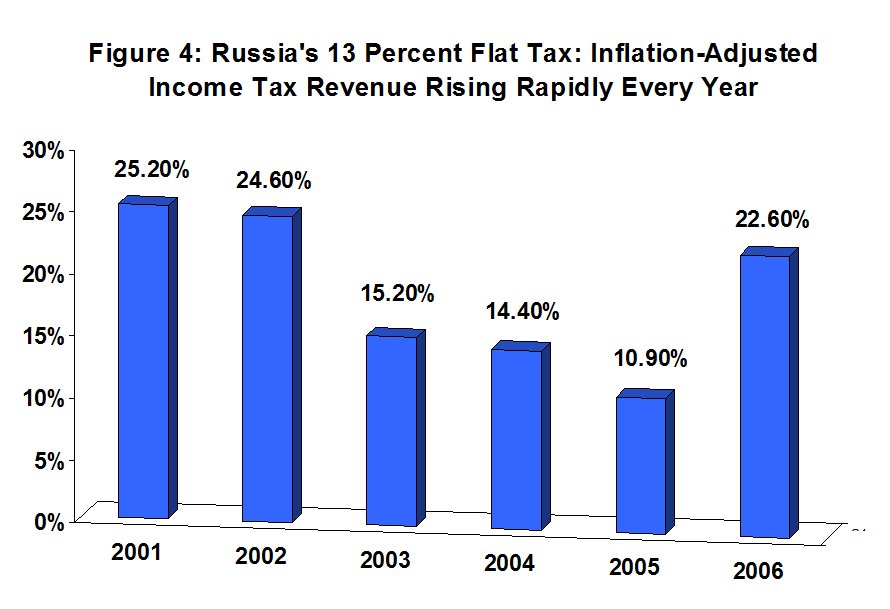

Russia and Ukraine also are enjoying respectable growth, though political unrest and the impact of rising energy prices make it particularly difficult to isolate the effect of tax reform. But even with the other factors, the Russian flat tax has had a remarkable Laffer Curve effect. As shown in Figure 4, personal income tax revenue has been growing at double-digit rates ever since the 13 percent flat tax replaced the old progressive system that had a top rate of 30 percent.26 These numbers are adjusted for inflation, incidentally, making the Laffer Curve effect even more impressive.

Rapid growth in former communist nations, to be sure, should be expected. These nations are recovering from decades of economic mismanagement and traditional economic theory suggests that they should enjoy more rapid growth as they “converge” with wealthier nations. The flat tax is noteworthy, though, since the nations that are more market-oriented-particularly with regard to tax reform-seem to be converging faster than the nations that are saddled with so-called progressive taxes.

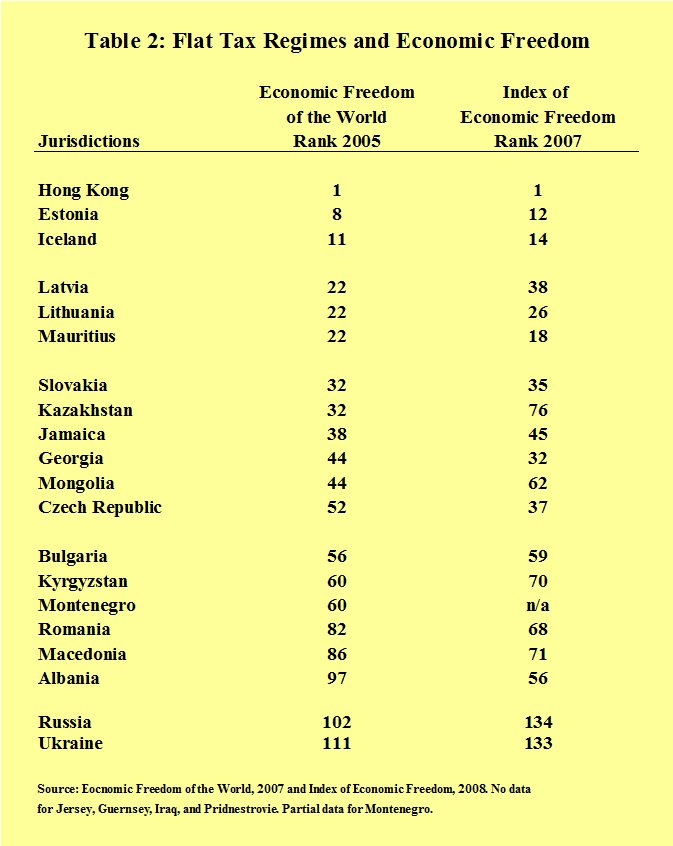

As mentioned above, the flat tax is just one aspect of tax policy, and tax policy is just one half of the fiscal policy equation, and fiscal policy is just one of the many factors that influence an economy’s performance. As illustrated in Table 2, flat tax jurisdictions do not necessarily get high grades for overall economic policy. Hong Kong, Estonia, and Iceland score highly. Lithuania, Georgia, Latvia, Mauritius, and Slovakia are examples of nations that do reasonably well. Other nations score poorly, with Russia and Ukraine earning especially low scores.

The Role of Tax Competition

Globalization has had a positive impact on tax policy because governments now have to compete. Simply stated, the geese that lay the golden eggs can fly away, and this discourages politicians from trying to pluck too many feathers. Capital is now extremely mobile across national borders, for instance, which makes it very difficult for governments to impose punitive tax rates on saving and investment. This applies to both direct investment (which occurs, for instance, when a company builds a factory in another nation) and indirect investment (which occurs, for example, when an individual purchases and/or manages portfolio investments in another nation). Competition to attract capital (or to keep it from fleeing) is one of the main reasons why the average corporate tax rate in developed nations has dropped by 20 percentage points since 1980.

Competition for mobile saving and investment also has encouraged countries to reduce or eliminate various forms of double taxation on capital. Some nations have low-rate taxes on individual capital income (dividends, interest, and/or capital gains). Others have eliminated or reduced death taxes and wealth taxes. In many cases, these reforms are adopted explicitly to encourage taxpayers not to move their funds out of the country. And because the personal income tax often is imposed on capital income, the tax competition-induced reduction in personal income tax rates also has helped reduce the tax burden on saving and investment. The average top individual tax rate in OECD nations, for instance, has dropped by more than 25 percentage points since 1980.

The Thatcher and Reagan tax rate reductions began the process of tax competition, and the global tax reform movement is the latest chapter. The flat tax revolution in Eastern Europe may be the first phase. The unanswered question is whether the flat tax will jump over the old Iron Curtain. This is why it is noteworthy that Iceland now has a flat tax. There also have been tax reform discussions in Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Finland, and Spain. In each case, the political obstacles were too severe, but it is remarkable that the flat tax is even being contemplated.

Conclusion

Twenty years ago, the Soviet Empire was a threat, both militarily and ideologically, to the free world. Today, the Soviet Union no longer exists and 18 nations to emerge from communism’s collapse now have single-rate systems – accounting for a clear majority of the world’s 24 flat tax jurisdictions. This tax reform revolution is remarkable, both because it signifies the spread of market-oriented policy and because it demonstrates that it is possible to have an income tax without following Marx’s dictate of “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

Thanks to tax competition, this flat tax revolution almost certainly will continue to spread. More nations hopefully will adopt flat taxes. Those nations will likely choose low tax rates. And countries with flat tax systems will probably shift to lower rates to keep competitive. The global shift to flat taxes means more growth in more nations. A flat tax does not guarantee robust economic performance, but it does mean that the tax code will be less of an impediment to productive activity.

__________________________________

Daniel Mitchell is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute (cato.org), a free-market think tank located in Washington, DC. He also co-founded the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation and serves as the Chairman of its Board of Directors. This Prosperitas is an updated version of a paper first published in June 2007 by Laffer Associates.”

The Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization operating under Section 501(c)3. It is privately supported, and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation, the research and educational affiliate of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity (CFP), can be reached by calling 202-285-0244 or visiting our web site at www.freedomandprosperity.org.

Endnotes

1Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka, The Flat Tax, 2nd ed. (Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, 1995), at http://www.hoover.org/publications/books/3602666.html (June 7, 2007).

2 There are several likely explanations for this development. People emerging from the economic deprivation of communism doubtlessly are anxious to catch up with their richer neighbors in Western Europe and the flat tax is seen as an effective strategy to attract job-creating capital. Having suffered under regimes that supposedly helped the poor, people in post-Communist nations also are probably less likely to be swayed by class-warfare arguments against tax reform. Additionally, low-rate flat tax systems are viewed as effective ways of improving tax compliance since the incentive to evade is reduced when the tax rate is less punitive. Last but not least, tax competition clearly is playing a role in recent years as nations scramble to adopt pro-growth tax systems in response to the successful flat taxes adopted by other nations in the region.

3 Michael Keen, Yitae Kim, and Ricardo Varsono, “The ‘Flat Tax(es)’: Principles and Evidence,” Working Paper 06/218, International Monetary Fund, September 2006. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2006/wp06218.pdf.

4 Some argue that places like the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas have flat taxes with rates of zero.

5 Tatiana Smolenskaya, “Russian Lawmakers Reject Bill to Unflatten Income Tax,” Tax-news.com, April 13, 2007. Available at http://www.tax-news.com/asp/story/Russian_Lawmakers_Reject_Bill_To_Unflatten_Income_T ax_xxxx26956.html

6 Marian Tupy, “The 18 Percent Solution,” TCSDaily.com, June 21, 2006. Available at http://www.tcsdaily.com/article.aspx?id=062006G.

7 On April 1, 2008, Hong Kong’s flat tax rate on individual income drops from 16 percent to 15 percent, and the flat tax rate on companies falls from 17.5 percent to 16.5 percent.

8 International Monetary Fund, “IMF Executive Board Concludes 2006 Article IV Consultation Discussions with the People’s Republic of China-Hong Kong Special Administrative Region,” January 8, 2007. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pn/2007/pn0702.htm.

9 Angus Maddison, “Historical Statistics for the World Economy: 1-2003,” at http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/Historical_Statistics/horizontal-file_10-2006.xls (May 24, 2007).

10 Michael Littlewood, “The Hong Kong Tax System: Key Lessons and Features for Policy Makers,” Prosperitas, Vol. VII, No. II, March 2007. Available at https://www.freedomandprosperity.org/Papers/hongkong/hongkong.shtml.

11 International Monetary Fund, “Republic of Estonia,” Staff Report for the 2006 Article IV Consultation, November 1, 2006. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2006/cr06418.pdf.

12 Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Estonia, “Tax Policy,” at http://www.fin.ee/?id=621 (May 24, 2007).

13 International Monetary Fund, “Republic of Estonia,” Staff Report for the 2006 Article IV Consultation, November 1, 2006. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2006/cr06418.pdf.

14 International Monetary Fund, “Slovak Republic-2007 Article IV Consultation Discussions, Preliminary Conclusions of the Mission,” March 13, 2007. Available at http://www.imf.org/external/np/ms/2007/031307.htm.

15 Martin Chren, “The Slovakian Tax System: Key Features and Lessons for Policy Makers,” Prosperitas, Vol. VI, No VI, September 2006. Available at https://www.freedomandprosperity.org/Papers/slovakia/slovakia.shtml.

16 Bradley Garner, “It ain’t Slovakia,” Czech Business Weekly, April 10, 2007. Available at http://www.cbw.cz/phprs/2007041031.html.

17 Invest in Iceland Agency, “Taxation in Iceland,” at http://www.invest.is/Doing-Business-in-Iceland/Taxation/#g8 (May 24, 2007).

18 Daniel J. Mitchell, “Iceland Joins the Flat Tax Club,” Tax and Budget Bulletin, No 43, The Cato Institute, February 2007. Available at http://www.cato.org/pubs/tbb/tbb_0207-43.pdf.

19 World Bank, “GNI per Capita 2005, Atlas Method and PPP,” World Development Indicators database, July 1, 2006, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf.

20 International Monetary Fund, “IMF Executive Board Concludes 2006 Article IV Consultation with Iceland,” August 8, 2006, www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pn/2006/pn0692.htm.

21 World Bank, “GNI Per Capita, Atlas Method and PPP,” May 1, 2007. Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf.

22 International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook… Available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2007/01/pdf/text.pdf.

26 Alvin Rabushka, “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Five, 2005,” Hoover Institution, May 11, 2006. Available at http://www.hoover.org/research/russianecon/essays/5805616.html.

_______________________________

Center for Freedom and Prosperity Foundation

P.O. Box 10882, Alexandria, Virginia 22310

Phone: 202-285-0244

www.freedomandprosperity.org